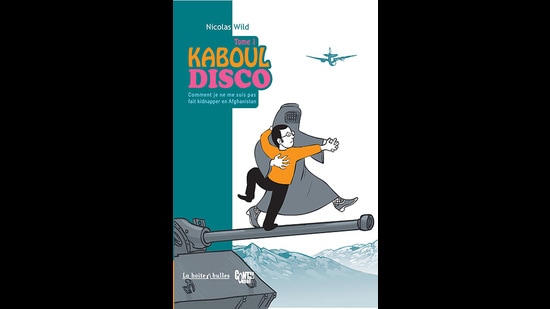

Interview: Nicolas Wild, author, Kabul Disco - ‘Being French and White gave me many privileges in Afghanistan’

A graphic novelist from France, best known for Kabul Disco Vols 1 and 2, was at the recent Kolkata Literary Meet. Here, he talks about his books, Afghanistan, and about representation

Indian readers know you mainly because of your Kabul Disco books since most of your other work has not been released here. When did you last visit Afghanistan?

My last trip to Afghanistan was in 2009. This was after I had finished working on both the Kabul Disco books. I went back because I was missing the place and the people. Having spent so much time there, I have a special feeling for the country. Unfortunately, it has been 13 years since my last visit. Many of the friends that I had made there do not live in Afghanistan any longer. They have migrated to other places with their families and their loved ones because it seemed safer to get out, and pursue a life that was less filled with threats to their lives every single day. What is happening there right now is very sad. I think of Afghanistan a lot but, honestly, I do not know when I will be able to go there again.

Yes, it true that many of books haven’t been translated from French into English, so they have not been published in India. I hope that will change. HarperCollins was a good publisher to work with on the Kabul Disco books. Amruta Patil, the Indian graphic novelist, introduced me to Karthika VK, my publisher who was then at HarperCollins. Initially, I wanted to do three Kabul Disco books but I ran out of material so I did only two.

How do you look at the politics of representation in those two novels? How was your experience and depiction of Afghanistan shaped by being French and white?

I was much younger when I wrote and illustrated those books. I knew very little about Afghanistan. I was just starting out there, and working on the graphic novels was more of a creative outlet to document and share my experiences. I was not trying to be an expert or educate anyone about Kabul. I was trying to make sense of what I was seeing around me. I do not pretend that it is the only way to see Kabul. It is my view, a French guy’s perspective.

Being French and white gave me many privileges, and it also made some people suspicious. I travelled a lot in Afghanistan. Apart from Kabul, I went to Mazar-i-Sharif, Bamiyan, Herat, Kandahar, and several other places. Tribal leaders were curious about why I was in their country, who I was working for, and whether I was a spy, but they were also bound by a traditional code of honour and hospitality. By custom, they are supposed to take really good care of foreigners, and feed them well. I must say that it worked out really well for me.

I must add that, as a guest, I too had to be responsible. Religion can be a delicate subject in a context like Afghanistan. It was okay to say that I was a Christian but it was important to be absolutely clear that I was not there to preach about Christianity or convert anyone. In France, on the other hand, the situation is quite different. Half the population is not religious. I observed that, in Afghanistan, people find it difficult to understand the concept of atheism.

Tell us about Kabul Requiem, a book you wrote after the Kabul Disco books.

This book was created in collaboration with Sean Langan, who is a British journalist and documentary filmmaker. He has spent a lot of time in Afghanistan. He has fascinating stories to tell, but also stories that would be quite scary to most people that I know. He was kidnapped by the Taliban when he was shooting a film in the border areas between Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has made many documentaries for BBC and Channel 4 in the UK. We met in France for a week. We watched the films together. He would stop during a scene, and then tell me more to give me some background and more stories because you cannot put everything in a film. You have to be conscious of the time and the audience. Based on his narration of his experiences, I created the graphic novel. I wrote and illustrated.

Who are the Afghan authors and artists whose work you tend to follow to keep yourself informed about the situation on the ground in Afghanistan?

After I got back from Afghanistan, I used to meet a lot of Afghans in Europe at parties and cultural events. There were shared memories to fall back on, things to reminisce about. But I have lost touch with people over time as I got busy with projects in Iran, Chernobyl, Nepal, Cambodia, Palestine, and Iraq. Life takes you in so many directions.

I am in close contact with Atiq Rahimi, who is a French-Afghan author writing novels set in Afghanistan. They offer important insights into the country and the culture. He is also a filmmaker. He makes documentaries for French television now but he grew up in Afghanistan. In fact, he went to a well-known school called Lycée Esteqlal. I know about it because it was run as a collaborative effort between the governments of Afghanistan and France. It had students from both countries, even children of French diplomats. Atiq left Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion. He was a teenager. He got political asylum in France.

What do you think about the way France, and Europe more broadly, have responded to the changing dynamics in Afghanistan? I mean after the fall of the elected Afghan government supported by the US, and the capture of power by the Taliban.

I think that France was a bit surprised by the way in which the US left Afghanistan after the talks between the American government and the Taliban in Doha. It seemed that the US troops would take more time to vacate the country, and put up a resistance against the Taliban, but that did not happen. In terms of people leaving Afghanistan, and seeking asylum in other countries, I think France has made a choice to prioritize people who worked for the French government and the French army in Afghanistan. They often put themselves in dangerous situations, so France has a moral responsibility to protect them and their families. A lot more could be done for the vulnerable Afghans. Just the process of filing visa applications can be so time consuming and frustrating. Things should not be so difficult.

What do you think of collaborations between French and Afghan artists to promote dialogue? Afghan refugees have concerns about Islamophobia in France, and the French have concerns about Afghans not adjusting to the French way of life?

That is a great idea. Secularism is something that is really important to French people, and sometimes it can create difficulties in accommodating people who are religious. And you are right; the cultures are different in terms of women and gay people’s place in society. There is Islamophobia in France, in fact everywhere in the world including India, but I think French society is quite open by and large. It is democratic, free and secular.

After Afghanistan, you lived in Iran for a while and even worked on a book there – Ainsi se tut Zarathoustra (Silent was Zarathustra). Tell us about that.

This book was published in India but the Kabul Disco books got more attention. It is about my explorations with Zoroastrianism in Iran. I travelled there because my friend Sophia had invited me. Her father Cyrus Yazdani, a famous man, was assassinated. I got really interested in his story when I spoke to people in Iran and learnt more about him. As part of my research, I also went to Geneva where the assassination trial was happening. The book is about him but it is also about Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s first monotheistic religions.

Indians, of course, know about Zoroastrianism because there are many Zoroastrians living here. In fact, I have also worked on a small graphic novel about Homi Bhabha, the Zoroastrian scientist from India who played an important role in setting up the nuclear programme. He died in a plane crash near Mont Blanc, which is in the Alps in Europe. I was very intrigued by that story. He was going to Vienna when this tragic incident happened.

That was a huge loss for India because he was the father of India’s nuclear bomb. While there is no evidence to prove that he was attacked, the theory or rumour that he was has been around. I built on that idea, so everyone comes in – the Cold War, CIA, Pakistan. Daniel Roche, a Swiss climber who went to the Alps, found some debris from a plane crash in the mountains. It could be from the aircraft that Homi Bhabha was on, or another Air India plane.

Tell us about your new projects.

My latest book, À la Maison des femmes (A House for Women), released during the pandemic. It has stories from a health care unit that provides support to vulnerable women in Saint Denis, a place in the northern suburbs of Paris. I am thinking of some other projects now. After the Kolkata Literary Meet, I am going to spend a few days in Delhi and meet Indian artists there. We have been discussing ideas for collaboration but it is early to tell you.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.