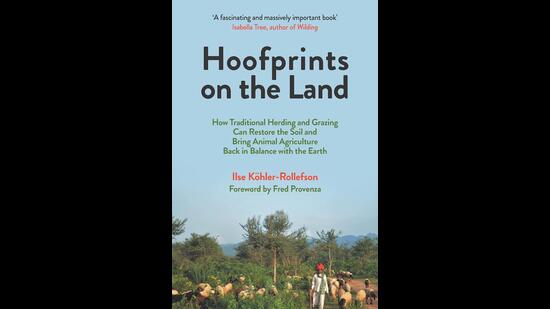

Interview: Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, author, Hoofprints on the Land - “We are part of nature”

On human-animal relationships, advocating for the rights of pastoralists, and working with the Raikas in Rajasthan for over three decades

What inspired you to write Hoofprints on the Land?

The book is inspired by my more than 30 years of working with pastoralists, with the Raika in Rajasthan, but also visiting many of them in other parts of the world. Maybe I should explain what pastoralists are: people who have a close relationship with livestock and move with their herds through landscapes. This may sound “backward” or “quaint” but is actually a way of life and food production that is, for one, very widespread and prevalent in huge parts of Asia and Africa, as well as parts of Europe and South America. Secondly, “pastoralism” entails solar-powered food production in harmony with the environment, without disturbing native biodiversity or using pesticides and herbicides.

What kind of readership are you targeting?

The book is for anybody who loves animals and cares for nature and the environment, also those readers interested in India’s rural culture. I hope it will be especially read by the many young – and older – people who are wondering whether they should go vegan out of love for animals and to prevent climate change. My message is that it is okay to eat both dairy and meat, as long as the animals have been kept in herding systems in which they had a good life and were raised in tune with the environment.

How does Hoofprints on the Land (2023) build on your previous books Keepers of Genes (2007) and Camel Karma (2014)?

Hoofprints on the Land takes a global perspective, and is much more comprehensive. Keepers of Genes describes how pastoralists manage biological diversity and how they have created a large number of livestock breeds, while Camel Karma is about my first 20 years of working with the Raika. Hoofprints on the Land summarizes my learnings from the Raika and then relates them to the many problems the world faces, including food security, biodiversity loss, land degradation, climate change, etc. It also suggests a fundamental change in how we look at livestock – not as input-output machines, but instead as creatures with intelligence and feelings that we have to manage as part of the environment.

You write about nomads as people who “live in harmony with the land” and in “partnership with their animals”. Why does it feel important to emphasize this in the contemporary world?

It is crucial for the world to understand that there are alternatives to industrial livestock keeping (which I feel should be banned), that mobile livestock keeping is part of our collective human heritage that has been suppressed and shunned since colonial times, and unfortunately was not reinstated when the colonizers left. Pastoralism means solar-powered food production and is something we urgently have to revive and support on a large scale to align agricultural practices with nature. It also provides organic manure, which is maybe even more important than the food it produces because it is crucial for India’s soil health and reduces dependence on fertilizer imports. On a higher level, we humans need to realize that we are part of nature and have to act accordingly by treating livestock as co-creatures, rather than considering ourselves as supreme beings that can control everything.

At the Jaipur Literature Festival, you will be in conversation with Anthony Sattin and Yashaswini Chandra. Tell us more.

I am really looking forward to this because I loved both of their books. Anthony Sattin’s book Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World (2022) shows how immensely important nomadism has been historically, while Yashaswini Chandra’s book The Tale of the Horse: A History of India on Horseback (2021) also relates to Rajasthan, but rather its more royal side. Hoofprints complements their books with the focus on ecology and non-royal people.

What are some of the most important things that you have learnt from nomads in Rajasthan?

I have learnt so much from them! First, of course, all that I write about in Hoofprints – how to keep animals as part of the landscape and to treat them humanely and prioritize their welfare over one’s own. Secondly, their attitude to life: flexibility, frugality, resilience, compassion: humanity in the face of adversity, and to never give up, but keep moving.

What kind of projects and initiatives in Rajasthan are you currently involved in?

I have been living in Rajasthan off and on since 1991. My main purpose has been to save its camels and the cultures they are embedded in. This started out with providing veterinary support when Raika asked me for it during my first academic research stint in 1991. But currently our main goal is to popularize camel milk and build up a camel dairy value chain. Together with Hanwant Singh Rathore, whom I first met in 1991, I set up Camel Charisma, a social enterprise which develops camel products. We ship frozen camel milk all over India to people with health problems, and we have developed a range of delicious camel cheeses which are purchased by top heritage hotels such as the Lake Palace. Also, we are providing camel milk for free to tribal children and to poor people with some amazing results. My goals for the future are two-pronged: for one, to convince the Rajasthan government to use camel milk in its midday meal and other nutritional schemes, because that way it can achieve camel conservation while also improving public health. Secondly, to develop and popularize an alternative “cruelty-free” way of dairying in which calves are not separated from their mothers. The idea is to popularize “planetary” rather than the ubiquitous “plant-based” diets. I am extremely excited about both goals.

How do your experiences as a veterinarian, researcher, activist, and teacher nourish your writing? What else would you like to write?

My writing is fuelled by my desire to share what I experience every day in my interaction with local people and with camels and other animals. I love living in rural Rajasthan, and there is so much to write about. About my next writing projects, I have a few. The next one will be about the camel cultures of the world and my search for an ethical human-animal relationship. It will start where Camel Karma finished, in 2014, when the camel was declared Rajasthan’s state animal, and the developments this has triggered since.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.