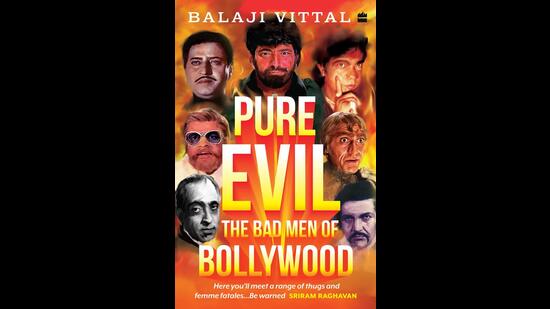

Interview: Balaji Vittal, author, Pure Evil; The Bad Men of Bollywood – “Film villains turned out to be exceptionally nice!”

Pure Evil: The Bad Men of Bollywood is your fourth book about Hindi films

Pure Evil: The Bad Men of Bollywood is your fourth book about Hindi films. Earlier, you co-authored a book each on SD Burman and RD Burman, and one on Hindi film songs. Tell us about your love of Hindi films, when it started, how it grew.

I remember Ye kya hua, Dum maro dum, and Pyaar deewana hota hai as some of the earliest sound waves emanating from the radio or the neighbouring Durga Puja pandal and shaping the soft clay of my sensibilities. My parents would take me to watch movies – both English and Hindi – quite regularly.

The earliest Hindi movies I watched in the theatres were Aradhana (1969), Anand (1971), Bobby (1973), and Jugnu (1973). I used to think that life was all about smiling, singing young men until I watched Zanjeer and this lanky young man who always seemed to be angry, who kicked chairs around, and punched anyone he did not approve of. And then Yaadon ki Baaraat (1973) was a mix of both varieties of men.

I merely soaked in these movies and their music from the age of two. Hindi films and music continued to be my primary recreation – apart from reading story books – and topic of discussion in school during breaks all through the 1970s and 1980s.

When I took admission in Jadavpur University (JU) in 1987, I plunged deep into the Film and Music quiz community. I developed a thirst for background information and trivia related to Bollywood. We used to have impromptu canteen quizzes and the hard-fought inter-college quiz contests at the college fests.

By the time I turned 20, the clay had hardened into a rock-solid Bollywood DNA.

How was the experience of flying solo after having worked with Anirudha Bhattacharjee as a collaborator on your first three books? How different was the writing process this time?

It was a tad uncertain at the beginning but, once I conducted the first few interviews with Bollywood personalities, my confidence surged. Mere interviews do not a story make, and it took me a good two years to be clear in my own mind about what the flow of the book should be. It was a highly iterative process but writing solo meant I could use my mind like a scratch pad to draft and redraft my story any number of times without having to check back with my co-author. But, of course, Anirudha and I enjoy a deep friendship since 1988 from our JU days, and I felt very comfortable seeking his opinion whenever I needed it.

Since you have been immersed in Hindi film music, tell us how music and background score have been used to develop the characters of Hindi film villains.

The background score can certainly enhance the character of the villain; for example, the banshee wail in the “Kitne aadmi the?” scene, which is Gabbar’s entry scene in Sholay (1975), the gargling sound when the villain Amitabh in Satte pe Satta (1982) is shown coming out of prison, or the long, shrill sound every time Kancha Cheena (Danny Denzongpa) in Agneepath (1990) makes an appearance, or the horn-like sound when Raghavan (Manoj Bajpai) in Aks (2001) appears. Don (both the 1978 and the 2006 versions) had a catchy signature tune every time Don appeared. It was originally a Kalyanji-Anandji tune but Shankar-Ehsan-Loy modernised it very well and used it in the introductory music as well as the interludes of the title song in the 2006 version. Unfortunately, these are the exceptions. By and large, background score has been used sub-optimally in Hindi films to enhance the villain character.

Your book has many kinds of villains – colonisers, bigots, scheming relatives, zamindars, moneylenders, dacoits, serial killers, smugglers, and more. How did you come up with the structure and the classification? Did you fine-tune it while editing?

Initially I made the mistake of putting the interviews with the Bollywood personalities in the foreground instead of the story. The book should ideally be about what the author wants to say, and the interviews could overlay the author’s story to substantiate it.

It took me two years get a grip on the basic storyline till, based on advice from my friends Kaushik Bhaumik and Amitava Chatterjee, I created a matrix with the various genres of villainy in one axis and the decades in the other axis. This gave me an arial “roadmap” of villainy down the ages. Next, I drafted a one/two-page summary of each chapter. This gave me the basic story of each chapter, which had eluded me all along.

Of course, the manuscript needed to be drafted and redrafted multiple times. Some of the villains had to be re-slotted elsewhere; for example, the villains involved in the Bombay Stock Exchange blast had to be moved from the section on mafia to the section on terrorists because mafia is usually not involved in terror financing. After I submitted the manuscript, my editor Rinita Banerjee pointed out that, while the coverage of the various genres was comprehensive, the characters were not getting fleshed out deeply enough. And then I practically rewrote the manuscript over the next four months!

As a child, which Bollywood villain(s) seemed most exciting or scary to you? Was there any villain that you wanted to be friends with, or had nightmares about?

Gabbar was very scary for a six-year-old me, as were the apparitions in Jadu Tona (1977) and Jaani Dushman (1979). But the one character that spooked me for many nights was Topiwala (Kader Khan) in Meri Aawaz Suno (1981). The torture scene in it was too much for a 12-year-old to take. On the other hand, I found the villains in The Great Gambler (1979) – Ramesh (Prem Chopra), Marconi (Sujit Kumar), Sethi (Roopesh Kumar) and Saxena (Utpal Dutt) particularly funny and cute. I wished I could have friends like those so that I could get to travel all over Europe with them at their expense.

What made you approach filmmaker Sriram Raghavan to write the foreword to your book? What do you find most striking about the baddies in his films?

I have been a big fan of his films and he had had been generous in his praise for my earlier books. I approached him for an interview, to which he kindly consented. I later went back to him requesting him to write the foreword. He agreed again! What a humble, easily approachable man he is! I loved his Johnny Gaddaar (2005) as it was an ensemble of villains and carried shades of retro Bollywood and vintage James Hadley Chase. While these villains were partners in crime, not one of them could be trusted; it was “blink-and-you-get-stabbed-by-your-buddy” all the way. Andhadhun (2018) was once again about sweet as sin characters who went about hacking kidneys, killing husbands, blinding young men and running people over on the highway. What I find different in his villains is that he adds faint shades of clumsiness to them that makes them look almost apologetic about their heinous acts.

While working on this book, you interviewed many actors who have played villains in Hindi films. Could you share some moments that left a strong impression?

Unlike Guddi (Jaya Bhaduri) in the film Guddi (1970) who perceived that all villain actors were bad people, I carried no such bias. These men turned out to be exceptionally nice and hospitable! They warmly welcomed me into their homes, treated me to tea and lunch, and they were pleased to hear that I was an author. They were also happy to know that a book on the roles played by them was being authored, so they shared insights about their roles and anecdotes that were not documented anywhere.

My interview with Yashpal Sharma happened in between a shoot in his make-up room. After the interview, the unit was ready for an outdoor shot in which the camera pans across a group of pedestrians. He asked me to stand at a nearby tea stall and pretend to chat with a few bystanders as the camera panned across. Who knows, I may have made my acting debut that day! I interviewed Kay Kay Menon by the poolside of the Raheja complex at Lokhandwala – standing up, with the laptop perched on my left arm and the right palm holding the recording device to Menon. After the interview, we sat down for coffee. It was almost 10 pm. I asked if he was headed home. He said, “No, I am waiting for the van to pick me up for a night shoot. 70% of my shoots happen at night.” With Kader Khan, it was an hour-long interview, post which I packed up, offered my sincere thanks to him and looked around, half-expecting Shakti Kapoor to be seated somewhere nearby. They were a strong pair in the 1980s.

You were in conversation with Manoj Bajpayee at the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF). How was it? How has he changed the face of the villain in Hindi films?

I have been a great admirer of his acting prowess right since Satya (1998). What I love about him is the way he puts in 100% even in a 14-min comedy short film called Ouch (2016). Look at the variety of roles he has played – the Mumbai gangster, the psychotic contract killer, the terrorist operator and recruiter, a rural mafia don. He challenges himself and sets new benchmarks in villainy. I cherish the time I got to spend with him at JLF 2022.

What is the role of make-up and costumes in representing evil?

Since cinema is a visual medium, every square inch of the attire, every touch of make-up is a brick that makes up the wall. I have dived deep into this aspect. For example, on the first day of the shoot of Hum (1991), actor Anupam Kher felt that something was missing in the characterisation of the rogue cop Giridhar. That was when Kher decided to shave his head and put on a different accent. Likewise, Amjad Khan’s khaini (tobacco) chewing while essaying Gabbar, or KN Singh’s smart tuxedo and dinner jacket that made him the first urbane villain in Hindi films. Some more examples would be Pran’s blue contact lenses in Ram aur Shyam (1967) adds to his ruthlessness, and Mogambo in Mr India (1987) would not have been Mogambo without those shocking pink and garish outfits and the blond duke wig.

Do you distinguish between the ‘anti-hero’ and the ‘villain’? The latter sounds less judgemental. Is there a shift towards recognizing that nobody is pure evil?

As filmmaker Shyam Benegal put it succinctly, a villain is a guy with a bad intent while an anti-hero is a guy with a good intent but the means that he chooses are wrong. The anti-hero is either dissenting against a corrupt system or seeking personal revenge, which is why the anti-heroes in Mere Apne (1971), Zanjeer (1973), Yaadon ki Baaraat (1973), Deewaar (1975), Trishul (1978) and Ankush (1986) invariably win audience sympathy.

These anti-heroes are not to be confused with the grey characters that have emerged in the last 25 years. These grey characters are ambiguous and are a realistic representation of a situational villainy. Don’t we demonstrate the same? At times, we are mildly irritated, and sometimes we are furious. Our state of mind and the resultant behaviour is a reaction to something. When there is nothing to make us angry, we are good humans, charitable, and helpful to neighbours. The ambiguity is what we term as grey on screen.

You write mainly about men who are villains. Do you believe that men have a special propensity for evil as compared to women and non-binary people?

I don’t believe that any one gender has a relatively greater propensity towards crime. In each section, I have made mentions of both males and females who demonstrated a similar antagonistic behaviour. Because the male and female villains co-exist in the same chapters, it might appear that the ladies have not got their due space in the book. But that is not true. In any case, there is a separate chapter called Mehndi Rang Layegi: Blood on Her Hands. That covers wives who schemed against their husbands and/or murdered them. Likewise in the chapter Pati, Patni aur Who? The Intruder, I have sketched unfaithful husbands as well as cheating wives who slept with their husbands’ best friends.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, you have dedicated the book to doctors, paramedics, nurses, caregivers, and officers involved in maintaining law and order for their “valiant war” against the “invisible villain.” Do you foresee a new category of villains in Hindi films?

Yes! How about a Far East country that manufactures a virus in its lab and lets it loose on the world? The other nations want to impose sanctions on this country but cannot as this country has invested billions of dollars in all those countries. Yes, maybe this can be an idea for a novel villainy.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, journalist and book reviewer.