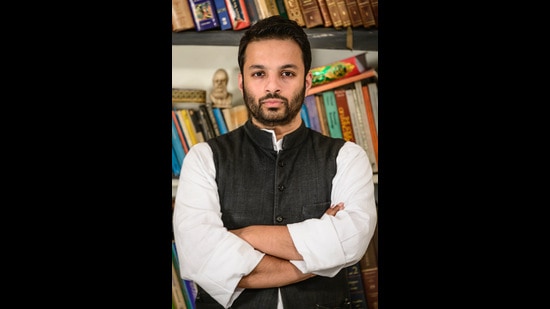

Interview: Ali Khan Mahmudabad, translator, The Break of Dawn – ‘This project was a very personal one for me’

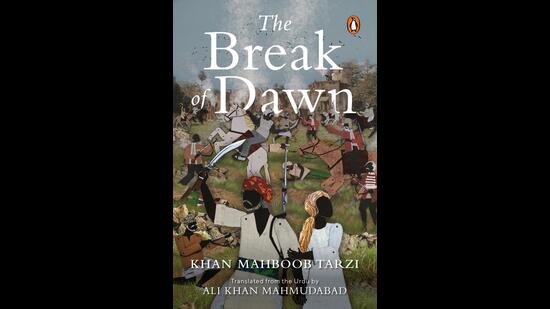

On the work of historical fiction set in 1857, the year Indians first rose up in rebellion against British colonial rule and fought for freedom.

MAA Khan, who writes under the pen-name Ali Khan Mahmudabad, is an Assistant Professor at Ashoka University. He conducts research in a number of languages including Arabic, Persian, Urdu and English. He is also a columnist, poet and translator. His last book, The Break of Dawn, is an English translation of Khan Mahboob Tarzi’s novel Aaghaz-e-Sahar (1957) originally written in Urdu. It is a work of historical fiction set in 1857, a year when Indians rose up in rebellion against British colonial rule and fought for freedom.

As a teacher of both history and political science, how often do you use historical fiction in your classes? Why does this genre excite you?

I recommend literature in my courses on history, Islam and political thought. I include novels, poetry, music and films on the syllabi to give students a flavour of different texts. Sometimes, I bring in historical fiction too. I think of it as a supplement, not a substitute. One has to be careful because it is fiction, not history.

What is interesting about historical fiction is that it makes historical characters come alive in ways that are difficult to execute in academic monographs. It helps readers enter the emotional worlds of characters, and understand how characters think. If it is well researched, it can bring forth some deep insights about the period and leave readers with a visceral feeling.

Aaghaz-e-Sahar, which I’ve translated as The Break of Dawn, is interesting because it was released exactly a century after 1857. India was a young country back then, and all countries do need a sense of themselves. 1857 represented a significant historical moment as it could be used to build a foundation for an Indian nationalism that was inclusive, and brought communities together.

From the historian’s point of view, that is problematic. In 1857, people rose up to fight the British for their own reasons. They were not a united front. There was regional politics, caste and class politics.

When Jawaharlal Nehru was writing his book The Discovery of India in the Ahmednagar jail, he dismissed 1857 as a failed feudal uprising. In 1957, when he stood in the Ramlila Maidan in Delhi to celebrate the centenary of 1857, he realized the power this event holds. And therefore, he called it the First War of Independence. This official recognition gave it a certain kind of importance.

It was in the same year, just a decade after India’s independence, that Aaghaz-e-Sahar was published. It is fiction but it archives how people of that time were imagining the nation.

Could you talk about how translating it helped you reconnect with your own family history, especially your great-great-great-grandfather Muqeem-ud-Daula Raja Nawab Ali Khan?

This translation project was a very personal one for me. It is linked, in some way, to what I set out to do with my first book Poetry of Belonging: Muslim Imaginings of India 1850-1950. It was about how Muslims of that time period expressed a kind of rootedness in India.

As I write in my introduction to The Break of Dawn, this project grew out of the anger I felt when my family members were called traitors in Parliament in 2017. It was a twisting of historical facts, making it seem that my ancestors sided with the British in 1857. This happened in an environment where the broader history of India’s Muslim pasts was being questioned, changed or eradicated.

In reality, Muqeem-ud-Daula died while fighting the British. My translation is a homage to him. Even though the book is a work of fiction not history, and he is only one of the many characters in what is essentially a love story between Riyaz and Alice, I really wanted to do something. And I did it.

One of the biggest problems today is the fact that we are so eager to categorize, slot and compartmentalize people according to one label that we forget the complexities. Right now, in our country, history is being mined to come up with grievances, which can then be redressed in the present. Events, personages and periods are being subjected to a kind of revisionism.

Two generations of my family after Muqeem-ud-Daula worked closely with the British, whether they liked it or not. My grandfather, my father and I all have had very different political affiliations. One generation should not have to answer for deeds of previous generations. To deny this complex history would be incorrect and unjust. One has to come to terms with what happened in the past without imposing one’s own narrow sense of self on it.

Since the subject of the book was so close to home, what feelings did it bring up in you?

The feeling was predominantly one of excitement. I read the book twice in Urdu before I started translating it. There was this sense of discovering, through a text, the life of an ancestor I had heard about as a child. I did not have much information because a lot of the older archives going back centuries were destroyed when the Qila of Mahmudabad was bombed.

The other exciting bit was about the Hindu rajas of Ramnagar Dhamedi being our blood brothers because of a pact signed between Muqeem-ud-Daula and Raja Guru Baksh Singh in 1857 to fight the British. Both of them appear in the novel.

A while ago, when I posted on Mahmudabad’s Instagram page about the book I was translating, I managed to connect with Anshika Singh from the Ramnagar Dhamedi family. It was totally out of the blue. I do not know if we have ever met each other; maybe we did when we were children. She too had been told the same story. It was almost a kind of childish excitement for me. After all, the stories we are told make us who we are.

I was also quite intrigued by the main storyline of Riyaz, a Muslim soldier from the rebel army, and Alice – a young English woman living in India -- falling in love with each other.

What was it like for you to study in England when, as a child, you and your brother would stand before portraits of British monarchs and stick your tongues out at them, holding them responsible for Muqeem-ud-Daula’s death?

I was 11, and my brother was eight. We were young and impressionable. I associated England only with 1857. I did not know what colonialism meant and how it worked but I knew that the British were oppressors. But I did not encounter any kind of racism. Once or twice when I felt I did, my mother was quick to tell me not to perceive myself as a victim. Acknowledging what is wrong is important but making victimhood the primary foundation of one’s identity can be dangerous.

When I was in boarding school at the age of 12-13, I was perplexed to find out that some teachers and students saw good in empire. I had to listen to them, and not completely block out their perspectives. It was an English, white, somewhat upper class, public school. I could not switch off. I had to learn to engage, understand, and if possible, refute.

At that point, I did not know that I would study history later. Some teachers did speak about colonialism as a civilizing force but, for the most part, I was not treated differently. My school also encouraged us to have our own opinion from a very young age. Praise is also due for that reason.

If you could use a time machine and go back to meet Khan Mahboob Tarzi, what aspects of the book would you discuss with him? Would the characters have a different journey if you wrote them?

I don’t think that I would write it differently because it is a great story as it is. I would ask Tarzi whether he had heard of a story like that of Alice and Riyaz. When I was a child, and my father was active in politics, a blond-haired blue-eyed man called Achche Agha used to work for him.

Our joke, as very young children, was that this man was a ‘leftover’ of the British. We used to make up a story that an Indian man who fell in love with an English woman had a child, and then that child grew up to be the gentleman we knew.

When Tarzi wrote the book, he was a young man. There must have been very few real-life witnesses of 1857 at that time. He might have heard some stories as a kid. I would ask him about those.

The text itself was not too difficult for me to translate because I have grown up speaking Urdu and the local village dialect. What was a bit challenging was to convey the kind of world these people inhabited, and the particular genealogies that are embedded within words.

The Italians, of course, say that the translator is a traitor.

I would also like to know from Tarzi whether he was actively thinking of 1857 as a moment of conceiving Indian nationalism. Was it at the forefront of his own mind, or did he just articulate what was part of the cultural milieu of that time?

That would be interesting to ask of a lot of writers and poets because some liberals and people from the left intellectually look down upon the whole idea of nationalism. Ignoring it is not necessarily the best thing to do. The fact is that nationalism is a powerful force. There is no reason to let it be monopolized by any one group, or expressed in ways that are inherently myopic and chauvinistic.

I was struck by this sentence: “Whoever behaves in a just manner with enemies and shows them mercy is truly a brave man.” What do you think about the way in which honour, bravery and loyalty are invoked in Tarzi’s book, especially with reference to prisoners of war?

The kind of living Islam that we grew up with, which included stories from the time of the Prophet, highlighted precisely these qualities of chivalry, nobility, honour and loyalty. In our context, they are partly related to the feudal order of things, so these categories do need some interrogation. However, they also come from a worldview that is not centered around the individual. There is something larger.

Of course, from a postmodern point of view, this is problematic because anything bigger than the individual – be it family, community, or society – is seen as a kind of hegemonic force that needs to be demolished. But at the same, notions of valour and justice are vital for a world in which material gain is not the only determining factor. There are values that matter beyond chasing materialism as a source of contentment.

In Islam, there are strict injunctions about conduct during war, especially in relation to women and children, old people, and property itself. Tarzi reflects these values that were treasured.

The book mentions bawarchikhanas for Muslim soldiers, and bhandaras for Hindu soldiers. Could you speak a little about the social context, and whether our current understanding of secularism is a lens that is helpful or not while making sense of what happened in 1857?

I wanted to foreground the fact that people were very rooted in their religion, and this rootedness helped them come together. The idea of Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb can be a bit dangerous at times because, in keeping with the liberal and socialist order of things, it has been promoted in the last few decades as a dilution of religious practices within communities. Our experience of living together in South Asia is quite different from the European experience of secularism, which is related to reform within the church and the separation between church and state. Of course, conflict has been very much a part of Indian society, like all societies, but we have found our own distinct ways to live in harmony.

There has been injustice and segregation. There is no denying that. That said, today, religion has been influenced by the forces of modernity. It has become more performative, superficial and dogmatic. When there were separate bawarchikhanas and bhandaras for Muslim and Hindu soldiers respectively, it was a way to honour their religious laws, customs and cultural mores. In my own family, I have seen separate arrangements being made to host guests. You can say this is entrenching difference or acknowledge that, when you honour differences, bridges will emerge.

We must remember that the Tarzi makes very little mention of caste groups. He was writing based on the milieu that he knew well. This is primarily an upper caste story. There was caste injustice at that time but it is not addressed. What we can take from Tarzi’s novel is how Muslims and Hindus related to each other, and that the desacralization of the world is not the only way to be secular.

In the introduction, you mention that Tarzi wrote science fiction and erotica apart from historical fiction. He also worked in the army, at a lock-making factory and in the film industry. Tell us more about him.

It was erotica but not by today’s standards. For me, a major source of information about Tarzi’s life was Umair Manzar’s book Khan Mahboob Tarzi – A Popular Novelist from Lucknow (2020). I also reached out to people in the Urdu departments at universities in Lucknow and Allahabad. I learnt that Tarzi was looked down upon. It reflected a certain bias. Tarzi and other writers were churning out novels at that time because there was a market for them. The erotica he wrote was written under a pseudonym. It was a way to earn his livelihood. One of the tragedies of his life was that publishers were taking advantage of him, and he was often hard-pressed for money. I want to translate some of his science fiction next. His descendants are now based in Karachi.

How was your experience of collaborating with Labonie Roy, who illustrated the book?

Labonie was a student at Ashoka University. I had seen her art, and it is certainly adds depth and new perspectives to The Break of Dawn. Initially, I wanted this book to be a graphic novel but I dropped the idea because I thought it may not capture what Tarzi was doing with Urdu. Labonie is tremendously talented. I invited her to Lucknow and Mahmudabad. She photographed real places, experimented with different materials like paper, cloth and wire scraps and came up with these mixed media forms that you see in the book. It took a lot of research. She has also incorporated objects, for example, a sword that has been in the family for a while. It belonged to Muqeem-ud-Daula’s son Ameer-ud-Daula. It originally came from the shrine of Najaf in Iraq. People may or may not notice these little things but they are there as silent witnesses of history.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, educator and researcher.