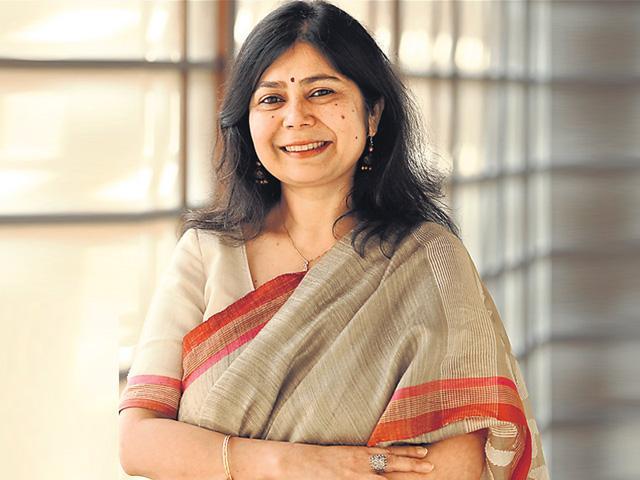

I am interested in both the world wars, says author Shrabani Basu

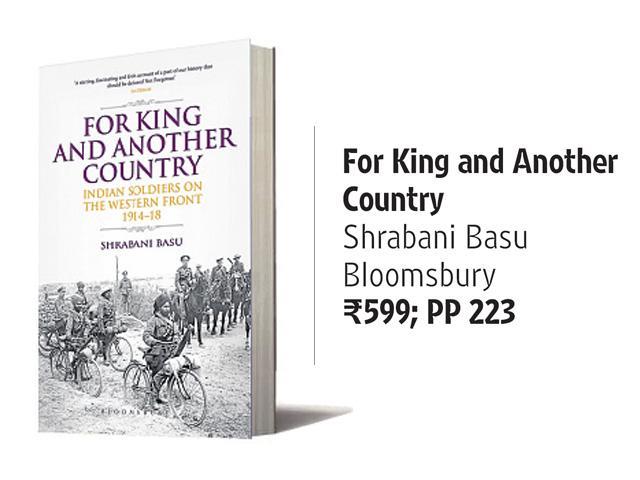

Over a million Indian soldiers fought in World War I. Shrabani Basu’s book recalls their forgotten history. An interview with the author.

Over a million Indian soldiers fought in World War I. Shrabani Basu’s book recalls their forgotten history. An interview with the author.

Did your book on Noor Inayat Khan spark an interest in the period when India was on the make and the empire was unravelling?

Britain, history, India — have always been my spheres of interest.

Were you looking for soldier-pioneers, or was there a particular side of World War I with an Indian connection that you wanted to explore?

I am interested in both the world wars. As the centenary was approaching in 2012, I thought what everyone will talk of is the Battle of Somme and the Battle of Gallipoli. No one will know about the Indians. If Noor, the woman who won the George Cross was forgotten, so would the soldiers. There were 1.5 million soldiers — for me that was the story. There were farmers, shepherds, who didn’t know why they were doing it but were risking life and limb for another country. From the First World War, we know the Tommies and their helmets. In the trenches, there were men in turban. It was a gathering of the largest number of people from the colonies. The greatest disservice would be to forget them. From Maharajas to sweepers to pilots — I didn’t even know there were Indian pilots in the First World War —I was learning about all of them as I went along. I found Sukha, the untouchable sweeper, in the hospital files.

Sukha is the one with the English girlfriend?

Sukha acquired a life of his own. His having an English girlfriend is fiction. When he died, people didn’t want to cremate him till the local vicar came up to bury him. The BBC mentioned him in a programme.

In your book, the Maharaja of Bikaner is quite a character. He is said to have participated in the war.

He and the other royals were constantly complaining of being kept four miles from the trenches. I guess to have Maharajas dropping dead in the trenches would not have been good PR. The Maharajas were literally asking the shells to hit them.

It was in the interest of the English to look after the men well.

There was always a contradiction. While on the one hand you had a ‘Comfort Committee’ with people like Lord Curzon in it looking after the smallest of wants — for example fine-toothed combs for Sikhs to comb their hairs to organising of Punjabi sweets called pinnis as the soldiers didn’t like English candies — on the other hand, they were very strict about the fact that there should be no White nurses to look after the Indian soldiers. There was to be no liaison between lonely English women whose husbands had gone off to the front and lonely Indian men. They were also clear about not having any Indian officers. After the First World War, this order was reversed as Indians began to be taken in as officers at Sandhurst.

Many as young as ten lied about their age and boarded a ship to go to Europe. Why?

You can always make out if someone is 10 or 18 – basically the English turned a blind eye. These kids, of course, mainly worked in the kitchens, kneading dough. But there were others who were in the trenches getting blown up. You had English officers like Walter Lawrence who complained that you couldn’t run wars with kids. Every week he wrote a report to Kitchener, the war minister. Why did the Indians go? They felt the loyalty to their king keenly. You had parents write to their sons saying ‘do it for your king, George Pancham’ as they called George V. It was impressed upon them that if you do well, you will bring honour to your village. I nearly called the book Salt of the Sarkar. There were other considerations. Laddie Roy, the pilot, for example, wanted to prove that the Bengalis, too, could be a martial race.

Read: Your daily does of life and style tips

What did the end of the war bring for all?

There was support for the war in the hope of a Dominion Status. It didn’t happen. Five months later, we got Jallianwala Bagh. This turned the tide. Tagore returned his knighthood. The Independence movement picked up after Jalianwala. There was aerial bombing of Gujranwala. Hardit Singh Malik, one of the pilots, who was to get married that Baisakhi day, called it the darkest day. The same planes he had been flying were used to bomb his own countrymen. Udham Singh was born out of all that.