HT reviewers pick the best books they’ve read in 2019

The list includes short stories, novellas, science writing, memoirs, and fiction that examines feudalism, patriarchy, fanaticism, marriage, and identity

Kunal Ray

Annie Zaidi’s novel, Prelude to a Riot left me numb. To say that I was deeply moved would be an understatement. It made me think about how troubled a writer must feel in contemporary India to produce a work like this. Set in an unnamed location in southern India, the novel revolves around two families – one Hindu and the other Muslim. Through a variety of characters and events built around them in the small town, the novel pulsates with the ominous air of a riot in the making. Some characters can sense trouble and refer to the riot as ‘it’ in fearful apprehension. Religious intolerance, labour rights, fanaticism, class conflict, the misrepresentation of history – all the ills that besiege contemporary India appear in Zaidi’s novel.

Prelude to a Riot will also be remembered for its finely etched characters – Dada, the ageing grandfather, Mariam, cook and masseuse, and migrant labourers Mommad and Majju, who represent the author’s deep empathy for the helplessness and vulnerability of people at a time of crisis. My personal favourite is Garuda, social science teacher at the local high school, who is trying to teach history to a bunch of disinterested students.

Zaidi makes an earnest attempt to unravel the psychology of a society that breeds dogma and fanaticism while eschewing all attempts at dialogue. When all conversations cease, conflict seems like a preordained eventuality. Censorship, oppression, and the denial of human rights has recurred in Zaidi’s writing. In her thoughtful non-fiction, she has constantly returned to many of these concerns, which she also brings to Prelude to a Riot thus making a definite statement about her politics and world view. Sample this: “I am not here now to help you read between the lines. Please read out of syllabus. A syllabus is ‘set’ for you. You understand? It is ‘set’ by people whose job it is to limit your knowledge. I am against syllabuses.”

Prelude to a Riot is a bold book, a work of remarkable artistic merit, courage, and vision.

Kunal Ray teaches literary & cultural studies at FLAME University, Pune

Lamat R Hasan

Shortly after his death in September, I decided to re-read Kiran Nagarkar’s Jasoda, one of the last novels he wrote. Nagarkar abandoned Jasoda for nearly a decade “like a standard MCP” till a German friend coaxed him into returning to it.

Given the author’s penchant for challenging toxic patriarchy as a novelist and playwright, I was prepared to read the story of a woman of steely resolve who stands up to both patriarchy and feudalism. But as I turned the pages, I could barely breathe. Nagarkar’s disturbingly graphic-yet-compassionate no-fuss-no-frills account of this extraordinary woman from the hinterland shook me to the core.

From managing food for her family from the neighbourhood’s lecherous grocer, to taking care of her ailing mother-in-law and being a dutiful wife to her abusive husband, Jasoda functions as mechanically as the cow she grazes in the barren fields of a village called Kantagiri.

What is especially gut-wrenching is the description of her unending role as a baby-producing machine. It’s easy to lose count of the babies she delivers as one reads on, but not easy to forget her expertise in delivering them. In the fields with another baby suckling on her, halfway up the staircase, and in between holding up the half-cracked mirror for her husband to twirl his moustache!

She lets the babies into the world with no help, often following up this ritual with their quick strangling, if they are of the wrong gender. A nurturer or a murderer – you wonder?

When just a handful of families is left in Jasoda’s parched nondescript village, she moves to Mumbai with her three sons and ailing mother-in-law. Life is far from easy there too, but the city gives her enough money and a comforting view of the sea. After spending seven years in Mumbai, she returns to Kantagiri, which is now buzzing with activity, and ends up being a restaurateur.

There are a few problems that affect the book. However, despite the shortcomings, Nagarkar’s quotidian heroine wins hands down.

Lamat R Hasan is an independent journalist.

Neha Sinha

In the ground, we bury what we love, and stash what we fear.

Robert Macfarlane’s new book, Underland, is described as ‘a deep time journey’. It starts with what is underneath the soil, but is really about our relationship with the earth and with time — and thus, equally to do with what is above soil.

In clear, rooted prose, Macfarlane conjoins adventure with geology, perspective with geography. He takes you down pits, caves, tombs and nuclear waste containers. There are journeys to Epping forest in London, a city under Paris (the catacombs, a cemetery below ground, framed by quarries), the Knud Rasmussen glacier in Greenland (a huge, icy monument, cracking in the modern world of our creation) and honey fungus that stretches over 2.5 miles in Oregon. Macfarlane draws a portrait of the world through places we don’t see, places full of wear and wonder.

This is science writing, but not presented as such. It reads like a loosely-plotted stream of consciousness, as if you are in a dark room listening to the author’s voice; the chapters like braids of rope in the dark. This is the book’s strength: though ecological and scientific in breadth, no jargon or footnotes crowd its pages.

My favourite passages are those on fungus. Most would give fungus a pass but Macfarlane carves a compelling study; these are beings that defy definition, that can crumble rock and “liquidate our sense of time.” They connect the roots of trees in the wood wide web.

Apart from the science, read the book for its literary shine. “Rivers of sap flow in the trees around us,” Macfarlane writes. If we place a stethoscope on the trunk, we would hear the sap “bubbling and crackling.”

In focusing on both the gigantic glacier and the minute lichen, the book is also about paying attention. A researcher in the book is quoted as saying: “if we’re not exploring, we’re not doing anything. We are just waiting.” In its quiet, intimate and assured tone, this is a tome on exactly why we should pay attention.

Neha Sinha is with the Bombay Natural History Society. Twitter: @nehaa_sinha

Percy Bharucha

2019 has been a good year for books. We’ve seen old favourites return with new hits and found new favourites to follow. In a year marked with fantastic debuts and new voices, it is nearly impossible to point to a favourite or the best book. But if there’s a book I’ve had the most fun reading this year, it is Upamanyu Chatterjee’s first volume of short stories The Assassination Of Indira Gandhi: The Collected Stories (Volume One).

Chatterjee exploits the potential of the short story form to its fullest. We find old characters like Agastya Sen from English, August and Jamun from The Last Burden play a fresh inning. There are several reasons this collection is to be celebrated: Chatterjee is a proficient wordsmith who uses historical figures, fictitious journeys, old heroes and contemporary issues to convey that the emperor is always naked. To make this point, he traverses vast swathes of time and space. His subjects include bewildered and homesick Sir Thomas Roe and his misadventures with inept translators and stubborn maharajas on his Bharat darshan tour; a father’s obsession with Othello and Shakespeare; thirteen-year-old students dealing with the aftermath of their classmate’s murder; a bored civil servant’s first contact with small-town India; and a young boy’s study of the absurd legal quagmire that is section 377.

While Chatterjee explores the various shades of humour, he enjoys examining the consequences of the trivial -- Sir Thomas Roe reading the book of Jehangir backwards having opened it the wrong way, and life imprisonment under section 377 hinging upon the definition of the word ‘penetrate’.

Another characteristic that endeared this collection to me is the vicious pragmatism of Chatterjee’s characters. He possesses an uncanny ability to articulate our darkest fears, our deepest beliefs, and the true nature of our behaviour. Underneath the humour that is characteristic to his work, Chatterjee hides devastating truths.

This collection is a fine balance where neither the truth nor the humour overpowers. Both are employed using a light touch and the subtlest of nods, making this a perfect note on which to end the year. It is introspective, nostalgic and will leave you in splits.

Percy Bharucha is a writer and illustrator with two biweekly comics, The Adult Manual and Cats Over Coffee. Instagram: @percybharucha

Saudamini Jain

Olive Kitteridge is one of my favourite characters in modern fiction. She is cranky and moody — and so honest, her tongue could cut leather. And now she is back.

In a scene in Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, the 2008 novel which won a Pulitzer and was adapted into an HBO mini series, Olive had run a marker across a sweater in her daughter-in-law’s closet and stolen a bra and a single shoe, delighting in the knowledge that this would cause bouts of self-doubt to the uppity woman her son had married. In the novel, Olive had raged at her gentle, pharmacist husband Henry and their son Christopher — and eventually lost them: Henry died, Christopher moved away and continued to resent his temperamental mother. Olive had aged, angry and more bitter — and hilarious.

In Olive, Again, which begins a few weeks after its prequel, Olive has softened in her late seventies. And the goodness at her core, the schoolteacher perceptiveness that made her instinctively understand the pain of strangers, is now extended to her family. She marries Jack Kennison, a Republican Ivy League type she had loathed, and they’re kinder to each other than they ever were to their late spouses. Her relationship with Christopher — and his second wife who has two other children by two other men, plus two of their own — improves significantly. The older she gets, the deeper her understanding of life and people in it.

Both books are set in the fictional town of Crosby, Maine. They’re a series of interconnected, but discontinuous and sometimes very loosely related stories about Olive and other locals. She only makes an appearance in some stories, sometimes other characters appear in her sections.

The Olive novels belong to a genre of fiction in which nothing happens. They’re stories of ordinary people in a small town — but Strout plunges into the dark undertones of their routine normalcy. She explores jealousies, anger, madness, fetishes, loneliness, and ominous interiority of characters in otherwise pleasant stories. We feel the weight and impact of dead mothers and abusive fathers. We get glimpses of the unbearable trauma that people carry — of loss, mental illness, cruelty, the messiness of everyday life.

Saudamini Jain is an independent journalist.

Simar Bhasin

Tayari Jones’ An American Marriage is the best book I’ve read this year. Centred on a wrongful rape conviction of an educated, middle class newly-wed African American, Roy, the novel charts how this incident shapes the lives of those connected to him. Told through the perspectives of Roy, his wife Celestial, and her close friend Andre, whom she comes to depend on, the narrative traverses the inner lives of the main protagonists, all the while piercing through the hollowness of the American dream. The impossible predicament that Roy and Celestial find themselves in and the unfairness of the entire situation is poignantly brought out in the letters they write to one another after Roy is put behind bars, where he writes on the difficulty of writing, of expressing, of wishing to rewrite. As he puts it, the challenge lies in his wishing “to write something on this paper that will make you remember me -- the real me, not the man you saw standing in a broke-down country courtroom, broke down myself.” The act of writing becomes the need to create a safe intimate space, perhaps with an awareness that these letters are read by agents of the state apparatus.

The exchange is suggestive of the state surveillance of coloured communities in the US. The communities themselves are striving to move out of an earlier generation’s distrust of the state. Yet, as in Roy and Celestial’s case, they are made painfully aware of the futility of such an exercise. As the narrative proceeds, Jones touches upon not only the enduring presence of racism in the fabric of American society but also takes on complicated questions about the institution of marriage, of motherhood, and of exceptional choices needing to be made against the backdrop of exceptional circumstances. Roy, Celestial and even Andre are not archetypal figures constructed simply to garner sympathy, but complex human beings, navigating love and life during difficult times. As Celestial writes in her first letter to Roy after his incarceration, “Our house isn’t simply empty, our home has been emptied.” By situating the unfairness of the US legal system in the private lives of those involved, Jones’ narrative becomes a heartbreaking and moving story about relationships and the struggle for survival in unjust times.

Simar Bhasin is an independent journalist.

Sonali Mujumdar

Business memoirs are unfamiliar terrain for me. So when I gingerly picked up Shoe Dog by Phil Knight a few months ago, I was not sure what to expect between its covers that display the most famous tick in the world. Shoe Dog is the Nike story -- the back story and humble genesis of the multinational brand and corporation, and its roller-coaster ride to success, in its creator’s warmth-soaked words.

The story began in the early 1960s with a 24-year-old wanting to make a difference by coming up with that one Crazy Idea, the thump of his heart matching that of his running step. Before he embarked on his mission, Knight set out on a dream backpacking tour around the world, wanting to “visit the planet’s most beautiful and wondrous places. And its most sacred.” The enchanting trip, which makes for only a few pages in the book, had quality Japanese running shoes as part of his larger adventure. A fanboy, Knight’s idea was to import the Onitsuka Tigers and sell them in the US market, then largely dominated by Adidas, partnering with his athletics coach David Bowerman, the design experimenter known for creating the waffle iron shoe. Impulsively, the shy boy from Oregon created the Blue Ribbon Company while standing before the inscrutable Japanese attempting to sell his idea to the Onitsuka Corporation. From selling shoes from his car at track meets to building a team from scratch, to becoming a global giant, Shoe Dog traces this remarkable odyssey of a start up and the mad struggle of a maverick’s venture. A story of grit, steely determination, and wisdom beyond age and sometimes reason, it is all strung beautifully together in lucid writing. It is a heart-warming tale of turbulence and triumphs, snippets about family and expressive portraits of the close circle of his trusty team mates who become family.

Shoe Dog exemplifies the fact that even the story of a global brand of shoes is better told when it has a soul.

Sonali Mujumdar writes, speaks French, and enjoys travel. She lives in Mumbai.

Sudhirendar Sharma

There is no denying that we are living in anxious times, not knowing where we are treading from day to day. What prevails is a ubiquitous lack of substance with a deadly insubstantiality, which has left us with a painful sense of inadequacy. Much evolved though it may seem, both society and systems have instead invoked Nietzsche’s fateful phrase: ‘Nothing is true, everything is allowed’. In this context, Roberto Calasso’s The Unnamable Present is a brutal but meditative enquiry into the indefinable present that urges us to give up courage, make cowardice a virtue, and see that both real and virtual war don’t end.

Pulling nuggets from the literature and philosophy of the recent past, the book examines the ongoing project of dehumanization that has blurred the distinction between the tourists and the terrorists. Aren’t both out there to destroy the creation of nature, he asks? With algorithmic information eating into human consciousness, mythomania has become the new normal. We only need to plug into it to ensure its constant supply. I found compelling reasons to agree with Calasso’s proposition that, much like the world that made a partially successful attempt at annihilating itself during the Second World War, our unnamable present too is hurtling down a murderous path. When was the last time we were shown such a hexed mirror?

The Unnamable Present leaves a lot unsaid that the discerning reader can find strewn between the lines. It is clear that the past continues to haunt us. Things return in a different form. People may have got rid of Hitler and Stalin but not the society that created them. The creation of democracy as an antidote to dictatorship has come to reflect a wishful nothing, extending to everyone the privilege of access to things that are no longer there, which lugs within it the seeds of self-destruction. Though it is not an easy read, The Unnamable Present should be credited for raising new questions on the transformation happening in our society.

Sudhirendar Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and academic.

Sujoy Gupta

As the momentum built up towards celebrating India’s platinum jubilee Republic Day on 26 January, 2020, I was quite surprised at the singular scarcity of valuable sociopolitical and socioeconomic literature on the “broad” subject of the Republic of India, not merely on the “narrow” specifics of our greatly respected Constitution.

The jinx was broken this summer by economist Surjit S Bhalla, Executive Director for India at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Despite its dour title and cover, his book Citizen Raj stands tall as the first contemporary chronicle that narrates and analyses the evolution of post independent India’s economic background and describes in simple language its unfolding over seven decades of erratic development.

Bhalla’s views are altogether cogent. He holds the reader’s attention through examining the fascinating evolutionary process of Indian democracy from its birth till today “and everything that has happened in between”.

That’s a long tale and Bhalla tells it with maturity though I’m a tad disappointed he doesn’t specifically echo my strong view that our republic is exceptionally resilient. For instance, it’s scarcely known that modern France is now in its Fifth Republic, born 1958. Its Fourth lasted only 12 years, 1946-1958. On the other hand, India is batting very well in its first innings.

To Bhalla’s credit, he doesn’t compromise credibility by ingloriously trying to be “politically correct.” He doesn’t balk at discussing the pros and cons of post-independence Nehruvian hegemony. He examines why demonetisation not only had zero positive effects but huge negative consequences. One of the major concerns of this book centres around caste. Last but not least, Bhalla takes a close look “at the way India ceded space to a man called Narendra Modi.” He doesn’t shy away from politics but is as apolitical as I am.

Read Citizen Raj. It is an extraordinary book.

Sujoy Gupta is a business historian and biographer.

Thangkhanlal Ngaihte

Issues of ethnic homelands and borders continue to roil the north east. Given this, the historian Pum Khan Pau’s monograph, Indo-Burma Frontier and the Making of the Chin Hills: Empire and Resistance marks a timely contribution to the existing sparse literature. It deals with the nature of relations between chiefs, kings and empires since the 19th century, the fluid and frequently-changing frontiers that marked influences or rule before the nation-state system with clearly defined borders imposed itself in the Indo-Burma borderlands. It makes our obsession with and fights over each community’s “ancestral homelands” look redundant and stupid.

Next is Sunil Khilnani’s Incarnations: India in 50 Lives. Khilnani blends serious scholarship with beautiful writing. Here, he explored the lives of 50 Indians, ranging from Kautilya to Birsa Munda to MF Hussain and Dhirubhai Ambani, distilling from their lives intelligence, wit, and uncommon wisdom. For instance, Gandhi’s sage words “Protect me from my friends, flatterers and followers,” seem to anticipate the present moment when power and influence are measured in terms of the number of followers on social media.

I also read The Caravan Book of Profiles. If Khilnani’s subjects are historical figures, Caravan’s deeply-researched and well-written profiles are on living, or recent, personalities. They form an eclectic mix. Vinod Jose’s introduction is superb.

Lastly, there’s Rakesh Batabyal’s JNU: The Making of a University. At the time of its founding, JNU was a truly national project with the best talents brought together to make it grow. It’s not just an institution, it embodies an idea. To read this book is to understand why that idea and that institution need preserving today.

Thangkhanlal Ngaihte teaches political science at Churachandpur College, Lamka, Manipur

Vivek Menezes

If one were to think of the comprised achievements of Indian literature as an immense library, the bookshelves reserved for quality autobiography and memoir would remain conspicuously bare. There are obvious exceptions – from Gandhi and Nehru to Dom Moraes and Nayantara Sahgal – but in this important category of letters Indian writers have consistently tended towards apologia and auto-hagiography, litanies of complaints or, most often, ritualistic score-settling. Good and reliable books in the first person that illuminate the post-Independence decades of the second half of the 20th century are an extreme rarity.

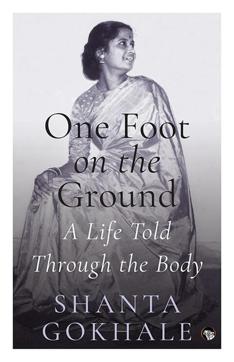

Such pure pleasure then, to encounter Shanta Gokhale’s gentle, grace-filled but unrelentingly clear-eyed Óne Foot on the Ground: A Life Told Through the Body, which artfully tracks the author from birth through the cusp of her eighties, via the framing device of various parts of her anatomy. Thus we have chapters titled, variously, Tonsils and Adenoids, Menstruation, Hair, The Nose, and eventually Glaucoma and a Fracture, as well as Full-Blown Cancer.

This rather unusual technique was always going to be a gamble. The author says in her introductory Chapter 0, “I have never looked at myself through the prism of my body. To look at it now, one organ at a time, remembering the circumstances that forced it on my attention in the course of my seventy-eight-year-old life, promises to be a heuristic exercise leading to another kind of self-knowledge than the one we normally aspire to. In the process of putting my body out there in plain view, I will also be keeping faith with my belief in transparency.”

Gokhale’s leap of faith has paid off in remarkable measure, because this is an astoundingly good and valuable memoir, loaded with acute insight about the times she lived through, and the people, places and circumstances that surrounded her. It’s certainly one of the very best books of its type that I have ever read. Huge congratulations are due the author, and also all those who encouraged and aided the writing and publication of this brilliant contribution to an otherwise undistinguished genre of Indian literature.

Vivek Menezes is a curator, photographer, writer and co-founder of the Goa Arts and Literature Festival