Home is where the light is

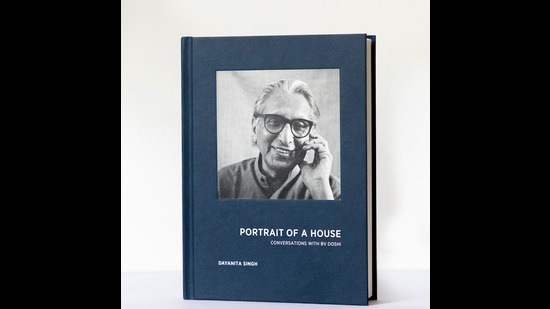

Dayanita Singh’s new book pays homage to architecture and photographic portraiture through conversations with BV Doshi

Portrait of a House: Conversations with BV Doshi begins with a foreword that is an excerpt from a conversation between architect and India’s first-ever Pritzker awardee, BV Doshi and artist and bookmaker Dayanita Singh about that “something else” in a photograph that might make it speak outside of its static, printed matter. What draws both Singh and Doshi into the conversations that follow is light — and how it guides both architecture and photography. An unusual photobook, Portrait of a House, is more an insight into both Singh and Doshi’s artistic practices drawing from their own deliberations about their mediums of expression. Singh took on a rare commission to photograph Doshi for a magazine in 2018 at his residence Kamala House, in Ahmedabad. Two years later, in the middle of the pandemic, during a conversation over Zoom, Singh showed Doshi the photographs.

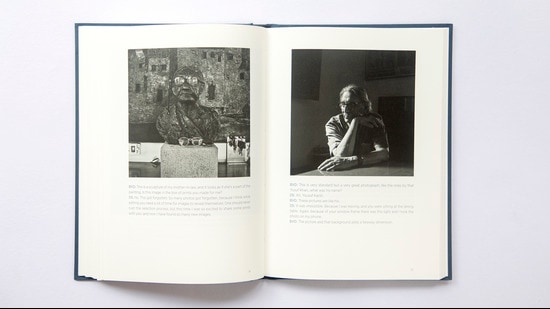

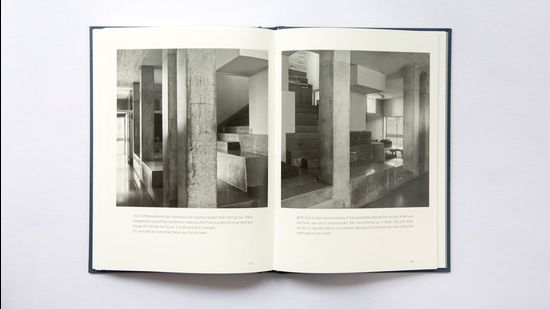

Dayanita Singh’s fine editing and bookmaking lets the conversations read like they move from room to room in Doshi’s home. Space in architecture is fluid, and so is the photographic portrait — and this is where both artists’ individual practices find common ground. Singh is clearly inspired by Doshi’s home, especially the way intimacies are designed to be encouraged and expressed in built spaces. “Really good architecture must first break the formality,” Doshi says about the premise behind his home and the relationships it holds. Singh’s strong, observed portraits of Doshi and his family are an extension of the spaces they are made in. The performance and portrayal of human architecture is fascinating, sometimes even more striking than what one actually sees of Doshi’s already remarkable home. For instance, on pages 40-41, two photographs of the same space in Doshi’s house, one each with Doshi and his wife in them, appear like a miniature theatre set, with several elements coming together and apart as Singh moves closer to make one image, and a bit away to make the other. And that’s when a self-confessed tricky question posed by Singh at the beginning of the book opens itself up to even more enquiry — “Are architects building spaces with the photograph in mind?”

Apart from the conversations around the photographs, the book is a good primer for those unfamiliar with Doshi’s beginnings and his individualistic design philosophies, such as the element of anticipation in architecture. Singh picks up on this philosophy particularly well, especially in her photographs of staircases that either leave room for the anticipation of a conversation, or interrupt an existing one. While photographing personal moments between family members in the house, Singh uses a phone camera — possibly a first in her books up until now. Doshi responds to these photographs with wonder and affection, while also regularly drawing comparisons to paintings from the Renaissance era, classical sculpture as well as movements in Indian classical dance forms. This is perhaps the only bit where Doshi’s commentary about the photographs feels a bit dated. Contemporary photography discourse has located its praxis well away from its previously debatable dependence on as well as inspiration from the classical painted forms.

Aware of how crucial patient editing is to the medium, Singh moves away from the visual denseness of personal moments to the outside. The garden, the visiting peahen, and a quiet insertion of even a self portrait lend a much needed casualness to the collaboration. Towards the end, the location moves to Maneesha House in Vadodara, a space laden with large columns that equally intimidate and intrigue. The abstractionist architecture gives Singh’s images a Wassily Kandinsky-like ethic — that of a measured, precise distance from reality.

Portrait of a House: Conversations with BV Doshi is also a family album and a rare peek into the personal life of one of India’s foremost architects. Singh gets the essence of good architecture and how it transforms a space into a place, in her photographs of Kamala House. As Doshi himself says in the foreword, “Most architecture photographs show shadows and light and hardness, but they should also have photographs which are soft.” Singh has perhaps found that “something else” after all.