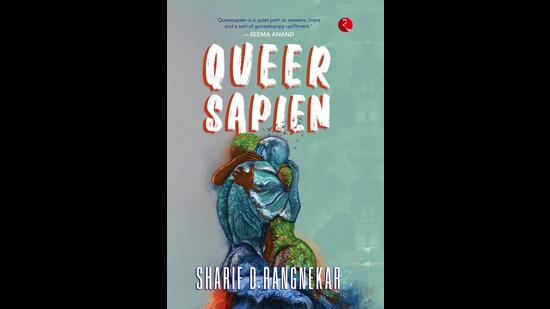

Excerpt: Queersapian by Sharif D Rangnekar

This extract from a book that’s part memoir and part social critique highlights the similarity between the nation’s freedom struggle and the queer community’s fight for acceptance and dignity

Ironically, it was on a flight to Thailand that I happened to re-read Rabindranath Tagore’s Where the Mind Is Without Fear, written over 120 years ago. It was a poem I was familiar with, as it was part of our school curriculum...

The poem “continues to exhort people – particularly in conflict zones across the world – to seek fearless truth, progressive thoughts and actions,” said Dr Badrul Hassan, a recipient of the Pablo Neruda Prize for poetry, in a write-up for the Reader’s Digest May 2020 issue. It was a “hymn for all mankind”, he claimed. And I couldn’t agree more.

I saw the conflict zones defined by gender binaries and roles, ideologies of the Left and Right, majority versus minority, mainstream as opposed to ‘other’ streams and the ability not to be limited by these divisions and tunnel visions of “either or”. I read the poem as an invocation for a life without trepidation, dread and distress that is experienced by most queer people, caused by an unrelenting heteronormativity and homophobia, which bear similarities with the British Raj ruling over minds and souls, robbing its subjects of their identity and sense of self.

...As children we read a fair bit about the independence movement. I listened to stories from relatives, on what the Partition had been like. I learnt that the day we got independence had been a solemn affair in most homes, given the loss of people and property many had incurred along the way, something we seemed to have forgotten when we celebrated the reading down of Section 377— “our” day of freedom.

...I have often wondered what it took to be a freedom fighter, part of a movement for independence, or what it is to be fearless, to hold one’s head high against all forms of oppression...

As luck would have it, I was blessed to meet Dadda, who was a freedom fighter. During a conversation in 1987, when I was 19 years old, he shared how he had abandoned his studies at my age, joining the Congress as a city committee secretary. Those days, he said, singing Bismil’s Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna, Iqbal’s Saare Jahan Se Achcha and Bankim’s Vande Mataram, had been weapons of expression against the Raj. He had been imprisoned four times, the first being in December 1921, for nearly three years, having taken part in the non-cooperation movement. He had slept several nights in long and large sewage pipes on the streets and gutters of Bombay, hiding from the British sepoys. His body had suffered a great deal of pain and ill health from time to time due to lathi charges, the lack of funds for food and medicine, as he had travelled from the north to west regularly... But, as he said, “That we could finally have our own elected government, nothing else mattered.”

Freedom fighters, he explained, had been part of an underbelly in British India, where they — a unified force cutting across religions and regions — could discuss their choices, indulge in their own culture and history while imagining a free nation. These dark and dingy places, he told me, had been hidden, known to a select few, as it had also been where strategies had been developed and networks had been built.

When I asked what it had felt like being ruled by the British, he said, “To be ‘ruled’ by anyone is to create fear, to humiliate and dehumanize the people of a land.” I asked him about the fear he and others must have experienced. This was the only moment I found Dadda struggling to reply... With half a smile, he... said: “aapko samaj hee nahin aayega…woh samay, woh dar…ek zindagi bina gaurav, bina izzat…yeh chota mota dar nahi tha, usse sehan aur zahan karna mushkil hain (you will not understand…those days…the fear…a life without pride, without respect…it was no ordinary fear, it is difficult to explain and was difficult to endure)!”

...several years later, once I had identified as gay, I grew to know how difficult it is to express what fear is, what it is to be denied respect and honour, the anxiety of a lurking danger and a system that is against you. While any such narration would revive wounds, as it did for me even in my 50s, I learnt that no vocabulary, however expansive, was close enough to the lived experience of a minority. Which is why my every effort to explain nervousness, depression and the impact of homophobia to most heterosexuals was often lost on them.

Yet, as some friends said, we could draw parallels with Dadda’s life as a freedom fighter and come close, not too close, to what he may have endured. That many of us lived without gaurav and izzat was a fact. That we had to create our own little underbelly and a few spaces here and there to feel free — to talk, to have fun and to work on a movement for equal rights and equity — as if we were in the pre-1947 era too.

The difference, though, as we all knew, was we were living in an independent India and were up against our very own people, parents and kin included, seeking freedom, not independence. We didn’t wish to leave our country just because we sought a place for ourselves. We didn’t want to be thrown out of our nation as well, just because our idea of life differed with the majority or that we saw much more in the Constitution than was “given” to us. We were averse to being called foreign or seditious just because our idea of India and being Indian wasn’t mainstream or of the majority.

We agreed that every person who came out was a freedom fighter, just by showing their defiance to the normative, the prevailing system. In the context of the movement, as Harvey Milk, America’s first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, said, it added to numbers and to safety. As a friend once said, it was like wearing a badge of pride, honour or bravery! ...

After coming out in 1999, it occurred to me that coming out itself was a process of learning to engage with people, places and circumstances. I had to use my gut feeling to pick people who I thought would treasure my secret. I had to know when to be free and when to keep my guard up. It was like finding the trusted few amongst a large majority of “traitors”. My safe spots then were at home, in my bedroom, at Venu and Chitra’s residence, at Arindam and Swati’s, and with my childhood friend Nitin and his wife, Rachna. I would glimmer with gayness when hanging out with queer friends, burst into colours at home get-togethers, and at the few parties hosted for us in and around the NCR.

Even in the mid-2000s when I started visiting Thailand, successful single men, aged 30 and above were often the target of gossip and suspicion of being gay, unable to marry a woman, something Arindam had warned me about. While the word “unable” implied an incompleteness in our manhood, many of us chose to ignore the hateful barbs, focussing on ways to fortify ourselves, at least in our places of work. It was sort of the same art of negotiating situations or picking battles that Ma had spoken about.

While there was no “one” way of being gay, I censored my gay humour or sexual innuendos, curtailed my hand movements, tried to hide any known giveaway of being a homosexual, such as a distinct tone and rhythm in my voice that seemed to be a little “lady-like”. I kept my attire quite bland, as colours were usually attributed to gay flamboyance, and wore a sleeveless Nehru jacket over cotton shirts, my only form of protest, that too against a suit-and-tie corporate culture inherited from the Raj. I also acted oblivious of any occasional conversations amongst my colleagues on the gay community. I even laughed at homophobic jokes and let occasional humour that reeked of sexism pass; after all, that was a commonly accepted attribute of being a man.

In a way, I chose to do what many Indians did when they moved to first-world countries like UK and the US, adopting the local food, culture, mannerisms, attitudes and accent, to become part of the clique and the power structure, expecting greater security and acceptance. This is also what traitors did, colluding with the British to obtain control, becoming one of them rather than being oneself...

While a number of my young colleagues got to know of my sexuality, it took me till I was a little over 45 years old, nearly a decade of leading the firm with several accolades in the bag, to come out to my chairman, who had always treated me like his son and family. All he said was, “Don’t worry, buddy!” Maybe I could have done this earlier, but then it was he who I reported to, the power above, and as Arindam had said, “Corporate culture and society are one and the same.”

The problem was that most of us felt compelled to put on an act and hide, internalizing a form of reprisal, absorbing the heteronormative culture that encircles us from birth onwards. It wasn’t unusual then or even now, therefore, for some gay men to look at themselves and life from a heterosexual lens rather than a queer one.

Helmer, for example, was unable to accept open relationships, questioning the veracity and love a couple had for each other, calling them immoral. He couldn’t comprehend my brief no-strings-attached friendship with a Thai man called Ton, that we weren’t boyfriends in the way boyfriends were meant to be. He was uncomfortable around effeminate boys and men, particularly those who powdered their face, used eye shadow and lipstick. He disliked anyone who’s hands moved much more than a man. Tight clothes revealing hard nipples, low-cut T-shirts and shorts, figure-hugging trousers and pants displaying the contours of private parts—all were a big no-no. He’d even get angry with street vendors selling gay porn, sex toys and Viagra.

A friend of his, a Danish lady who had spent over a decade in Thailand as against half as many by Helmer, said he had come from a tiny village dominated by the Church and had grown up with its dismissiveness of homosexuals... it isn’t unusual to hear such stories in Delhi even now or across several parts of India.

There were a number of lines of work that attracted ill-informed reactions and homophobia: that a gay doctor, nurse or counsellor would “convert” and sexually assault young, male heterosexual patients. The situation was such, I was told by a friend, that ‘if a heterosexual male doctor preyed on his female patient, the chances of hushing that up were greater compared to a person “appearing” gay, setting off “malicious” rumour mills, enough to destroy his career!’ And since such rumour mills were real possibilities and occurred in general, daily life too, it wasn’t unusual for some of us to seek “straight acting” men rather than being caught out with a queer femme person who was obviously gay to the straight eye. Yes, some of us were guilty of discrimination against our own!

...

Still, life was relatively much easier for a cis-gender man such as me. I identified with my given and assigned gender. Unlike a queer femme person, I didn’t feel womanly, nor did I desire make-up such as eyeshadow, lipstick and other cosmetics that ladies usually wore. I wasn’t apparently effeminate either. However, for those that were “queeny”, campy and effeminate, it was impossible to avoid drawing attention towards themselves or hide their identities.

One of my dearest friends, a queer femme puppeteer, Varun Narain, was subject to bullying throughout his schooling for being woman-like. Heterosexual boys would corner him during recess, in the toilet, on the school field and in the bus to and from home. They’d feel him up, terrify him. “It was power play, of showing their manliness,” he said. “I wanted to die so many times,” he told me, saying how much he hated his school days. Varun grew into a recluse, living mostly in his room and the attached garden, using puppetry and theatre to define his sexuality, courageously putting on shows in ‘safe’ parts of India and the world. With a mixed feeling of relief and ire, he said, “I would have ended my life without my art and the spine that my mother is!”

... This terrifying out-of-place feeling was not limited to gay men and queer femme folks. Lesbian women who appeared butch and didn’t like dolling up were taunted and told to “look like a woman”. Some of them were raped by parents and relatives in an effort to convert them to heterosexuality, a truth, as I said earlier, that hasn’t gone away yet. Smruti Jalpur, another of my singer-songwriter friends, told me that when she moved to Delhi, bars and restaurants asked her to replace her pant and shirt with skirts and dresses. They told her to be a woman — grow her hair, reveal her cleavage, put rouge on her cheeks, kajal on her eyes, lipstick on her lips and paint her nails! Why? Men drank more if they saw a woman looking like a woman on stage, an acceptable norm. Aise hi hota hain! (It is what it is).

Certain global reports find that people from the queer community are at two to six times greater risk of mental health problems, caused largely by the fear of hate, isolation and homophobia imposed by society. Some private Indian research say that over half of the gay community has considered suicide at least once in their lives. And if we deluded ourselves to believe that the world has changed dramatically after the reading down of Section 377, an August 2021 survey conducted by the online LGBTQIA+ community “Yes, We Exist”, says of the 1,700 folks polled, 75 per cent are “afraid that they might face verbal or physical abuse” if they lived freely.

The only measure of loss due to homophobia in India, however, is stated through economics in a 2014 report of the World Bank, which estimated the cost of homophobia in India at 0.1 to 1.7 per cent of the GDP. That is anywhere between USD 1.9 and 30.8 billion!

Ideally, these findings should have been headlining print and television news at that point, leading to debates and editorials on mental health and the queer community, but it didn’t.

... With such a life, many queer people then (and even today), sort of continue to be freedom fighters like Dadda was. We play hide and seek with the system, winning a skirmish here and there, engaging, on a daily basis, with the conflict zones Tagore referred to. ..

As a mental health expert said to me, living in Delhi, “we are like pieces of cloth torn in different places,” knowing full well that some of us could run out of threads to hem the damage.

I, as it were, would run off to Bangkok, drape myself in one piece of gayness, torn only by the prospects of returning to the roles and boxes that society confined us to in my homeland.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website