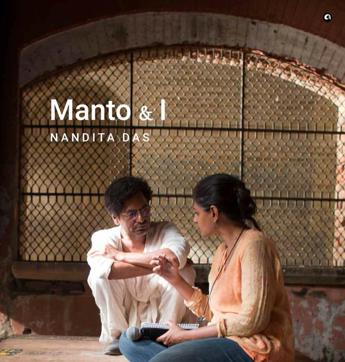

Excerpt: Manto & I by Nandita Das

In this exclusive first excerpt from Manto & I by Nandita Das, the author says her 2018 biopic on the great short story writer grew out of her admiration for Manto’s free spirit and his courage to stand up against orthodoxy of all kinds

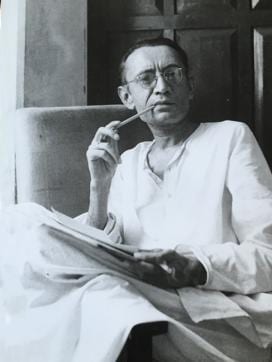

I first read Saadat Hasan Manto when I was in college and was struck by his simple yet profound stories. For a long time, I had wanted to adapt his stories into short films. But it was only in 2012, his centenary year, when much was being written about him, that I was introduced to his essays. It was then that the seed of this film was sown. And before I knew it, the journey of making my second film had begun.

What gripped me about Manto was his free spirit and his courage to stand up against orthodoxy of all kinds. No part of human existence was a taboo for him. His stories were never about the large events, instead they were always very intimate. His protagonists were often those on the margins of society, such as the pimp, prostitute, local thug or tongawala. He saved his most empathetic gaze for women, especially the sex workers whom nobody was writing about.

Manto’s socio-political concerns are embedded in his stories. And that deeply resonates with me. It is amusing though that he said, “I know as much about politics as Gandhi knows about films.” That is possibly because he never perceived himself as an activist or even political, despite writing stories such as Jallianwala Bagh, The New Constitution, essays about Bhagat Singh, and his famous Letters to Uncle Sam. They are all deeply political, but the storytelling remains intimate and the lens, humanistic. I have subconsciously found myself doing the same and that is reflected in both of my films, Firaaq and Manto.

Today, we are still grappling with issues of identity — which are inextricably linked to caste, class, religion, and gender as opposed to seeing the universality of human experiences. We have learnt little from history. We still find many reasons to build walls and too few to build bridges. Had he been alive today, he would have much to say. But for that, he would have been put behind bars or even been killed! Today, censorship is no more just institutional but has also expanded to unconstitutional outfits that claim to be custodians of culture and morality. Moreover, the dangerous phenomenon of self-censorship, born out of growing intolerance and fear, has become the order of the day. Artists, writers, activists, students are all battling for freedom speech. A society can only grow when it encourages its writers and artists to be its conscience, reflecting its diverse realities. From the time I started making the film, Manto’s relevance has only increased.

Although Manto detested labels, it would not be wrong to call him a feminist of his times. It was evident from both, his portrayal of women characters in his stories, and his relationship with the women in his life. Many of his stories were women-centric, in which he painted them not as victims, but as women who were in charge of their own destinies, for better or for worse. In Manto’s times, women didn’t occupy much of the public space, but he was surrounded and deeply influenced by them in his personal life. Be it his mother Sardar Begum, his sister Nasira Iqbal, his wife Safia, his daughters Nighat, Nuzhat, and Nusrat, or his friend and fellow writer, Ismat Chughtai— they all played important roles in his life. There are many stories about how respectful and caring he was towards them. But never in a patronizing way.

Manto was a modern man, much ahead of his times. He had such a deep understanding of women — their sufferings, struggles and strengths.Once when Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi asked Manto how he understood women so insightfully, he replied, “to understand a woman, you have to become one.” This is a rare statement for a man to make. I have been told by audiences across screenings that they found the female lens palpable in the way I portrayed a ‘feminist’ male protagonist.

As I plunged deeper into Manto’s life, I wondered why he seemed so familiar. I soon realized that it felt like I was reading about my father, Jatin Das. Baba, as I call him, is an artist. And much like Manto, he is instinctively unconventional, fearlessly blunt and often misunderstood. The uncanny similarities between Manto and Baba didn’t stop there. Baba too paints in the midst of chaos, likes to cook, is a stickler for cleanliness, keeps his doors open to not just friends but even to strangers, and is a loving father. Just like Manto, he has never valued money and is generous to a fault. Having grown up with a father so ‘Mantoesque’, helped me understand my protagonist more deeply and intimately. After having gone through the film’s journey, I have realized that I can only ever be half as maverick as either of them!

For the longest time in India, Manto has been respected in literary and theatre circles and many name him as one of the greatest ‘Indian’ short story writers ever. But in newly formed Pakistan, an Islamic state, to read Manto was considered almost blasphemous. A man who drank and wrote ‘obscene’ stories was not considered ‘decent’. Nonetheless, Manto was widely read and admired in literary and theatre circles in Pakistan. Moreover, in 2012, a hundred years after his birth, the Pakistan government posthumously conferred on him the Nishan-e-Imtiaz, their highest civilian award. I am delighted that in both countries, the film has further increased interest in Manto and his works. And who better than Manto, who belongs equally to both countries, to bridge the fissures between the hostile neighbours?

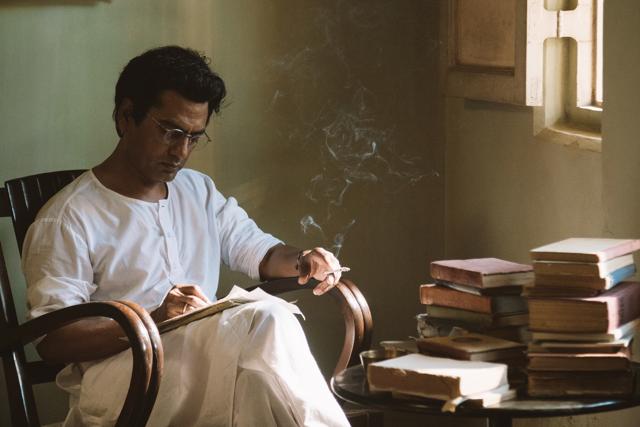

Manto’s own compulsion to write is evident from the fact that he was so prolific. Both Firaaq and Manto were driven by my compulsion to tell those stories, and not just out of a desire to become a director. I felt as if I were his kindred spirit, and that is why the more I got to know about him, the surer I was about making the film. The initial excitement didn’t wear off and has sustained itself for seven long years — from making the film to now writing the book.

Read more: Saadat Hasan Manto, the family man

Taking refuge in history also allowed me to engage with many of my concerns without being didactic. If the film was set in today’s times, it would have invariably polarized the conversations and responses to it. Manto gave me the opportunity to express my present concerns without having to worry about preconceived notions. Finally, viewers take from the film what resonates with them. If they come out of the experience feeling more disturbed, more alive and more inspired, I feel my intent has reached them. For me, Manto is not just a celebration of the man or the writer, but a celebration of the idea of ‘Mantoiyat’ — the will to be free-spirited, honest and courageous.