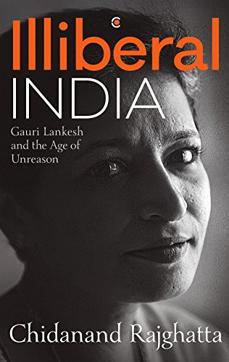

Excerpt: Illiberal India; Gauri Lankesh and the Age of Unreason by Chidanand Rajghatta

In a book that is both personal and political, Chidanand Rajghatta examines his own life and that of his former wife Gauri Lankesh against the backdrop of an increasingly intolerant India. This excerpt foretells the Karnataka police’s latest findings linking radical Hindutva forces to the September 5, 2017 murder of Gauri Lankesh

Based on his ‘social activity’ and profile, police surmised that Kumar, also called ‘Hotte Manja’, probably on account of his paunch (hotte is stomach or paunch in Kannada), had close links to rightwing outfits, including an organisation called Hindu Yuva Sena. They did not want him to vanish into the vast expanse of Bharatavarsha as had happened with men such as Rudra Patil, Sarang Akolkar, Praveen Limkar and Vinay Pawar, all suspects in the Pansare and Dabholkar murders. Extremism of every kind has its protective ecosystem in India, and it is not difficult in a vast country of 1.25 billion people for people to disappear and reinvent themselves.

Of course, the conspiracy theory was that the Siddaramaiah government wanted to arrest the perpetrators as close to the Assembly elections as possible to gain maximum mileage out of extremist rightwing involvement in the murders of Gauri and Kalburgi, and their ideological comrades in Maharashtra, Pansare and Dabholkar. But my contacts in the administration insisted that this was not the case. The SIT wanted to crack the bigger plot: forensics in the case was increasingly pointing to the same weapon having been used in the Gauri-Kalburgi shooting, and the same vintage of weapon, possibly even the same weapon, in the Pansare-Dabholkar murders. This went beyond Kumar; in fact, he may have been just the facilitator who carried out the recce and ferried the killer to Gauri’s home, the police said, not the one who pulled the trigger.

Indeed, that is what Hotte Manja maintained under questioning, according to the police. A group of four or five men from somewhere outside Karnataka had reached out to him via an intermediary in Mangalore. He had helped them with the logistics, including taking them to a forest near Kollegal for target practice, where they tried out different tactics with a country-made weapon: close-range shooting, longer-range targeting, shooting at moving targets, etc. As he understood it, their target was the rationalist KS Bhagawan, whose incendiary views on Hindu gods and scriptures, which Gauri shared to a large extent, had attracted their ire. But Bhagawan’s home in Mysore’s Kuvempu Nagar was on a busy street and it was hard to target him, so they had changed their plans. Who were they? Hotte Manja told the police he had no idea.

Why he helped them was clearer. Even as the SIT was authenticating and piecing together his dodgy tale, there was no doubting Hotte Manja’s political, social and religious views. Plastered across his Facebook homepage was a vast map of ‘Akhand Bharat’, a pan-India expanse showing a saffron sweep from the Gulf of Hormuz to the Straits of Malacca with the words ‘Aisa hi banane ka sankalp hai’ (determined to make this a reality). Another photo showed the back of a ‘Hindu leader’ holding aloft a sword in one hand and a saffron flag in the other; a third photo showed a mob marching through a street with scores of swords drawn and saffron flags flying between them.

And just in case you missed the cues, posted helpfully under that photo by a like-minded friend named ‘Abhishek Gands Kesari Khadga’ was a photo of AK-47 assault rifles with the caption in Kannada reading ‘Rama bhaktara kayalli banduka bandare Talibanigaligintha ugraroopa’—If Rama devotees get their hands on these guns, they will be even more fearsome than the Taliban.

This was the true face of militant Hindutva extremism — one that Gauri knew existed; and one that the majoritarian sentiment in India remains in denial of for the most part; one that wants to turn a secular, plural, multicultural, multi-religious, multi-lingual India into a Hindu version of Pakistan.

When and how did all this happen? And did such views flow from the politics of the day, or did politics begin to represent such views? As any student of Indian history knows, these issues have always existed in India, going back to the freedom movement that culminated in Independence and the subsequent assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by Hindu extremists. The bigotry that characterised those years has never really gone away. It has remained on the margins, and resurfaces often, trying to worm its way back into the national mainstream via politicians who tap into emotive nationalism and exclusivism.

All these issues came to a boil on a mellow post-Christmas December day in a moment that was singularly revealing about where Hindutva hardliners would prefer India to go.

An unabashed Hindu nationalist and RSS panjandrum, Anant Kumar Hegde hails from Uttara Kannada district, the coastal north Karnataka belt that lies south of Goa. A five-time Member of Parliament whose constituency has repeatedly rewarded him for his extremist positions, Hegde has no bandwidth for the niceties of Govinda Bhatta and Shishunala Sharifa embracing each other, or the syncretic nature of the Baba Budan Giri shrine.

At an event organised by the Brahman Yuva Parishad in Karnataka’s Koppal district in December 2017, just weeks after Gauri’s death, Hegde lit into ‘secularists’ who, in his mind, commingled all too easily with people of other religions and ethnicities. ‘If someone says I am a Muslim, or I am a Christian, or I am a Lingayat, or I am a Hindu, I feel very happy because he knows his roots. But these people who call themselves secularists,’ he frothed, ‘I don’t know what to call them. They are like people without parentage or who don’t know their bloodline. They don’t know themselves. They don’t know their parents, but they call themselves secular. If someone says I am secular, I get suspicious.’

In other words, if you are secular, you are a bastard; secularists are bastards.

This astonishingly candid display of fanaticism was not the most shocking part of it. Many Hindutva extremists are rabidly outspoken in their religious exclusiveness and racism, as are Muslim radicals and Christian fundamentalists in their lairs across the world. What is remarkable is that Hegde was a Union minister whose word, one can reasonably assume, reflects the official line and thinking. The BJP, Hegde continued, would ‘respect the word secular for now since the Constitution mentions it, but the Constitution needed to change from time to time’. The BJP had come to power to do precisely that, and would do so in the ‘near future’.

Hegde never lost an opportunity to burnish his Hindutva credentials, wrapped in nationalist colours. The blog Churumuri, at once insightful and acerbic, called him, among other things, a ‘mouth ka saudagar’ who spewed ‘venom, poison, bigotry, hatred, misogyny, resentment without ever receiving an intra-office memo on decency of language and behaviour’ that the RSS insists on for its members. ‘Hegde’s CV has all the Key Performance Indicators of a first-class Hindutva lab rat: rioting, unlawful assembly, promoting enmity, violating prohibitory orders, hate speech,’ the blog noted. ‘Is the unhinged verbalisation of the 49-year-old Brahmin, designed to keep the communal cauldron on the boil, his tatkal ticket to the Vidhana Soudha should the BJP come close to its next “Mission 150” in the 2018 assembly elections?’ In other words, it asked, was the BJP lining him up to be the next chief minister of Karnataka along the lines of Yogi Adityanath in Uttar Pradesh?

Unsurprisingly, the northern end of Hegde’s parliamentary district forms the tri-junction between Karnataka, Maharashtra and Goa. It is the stomping grounds of Sanatan Sanstha, the radical Hindu organisation that has come under scrutiny following the murders of Pansare, Dabholkar and Kulkarni, all of whom were familiar names in the political-academic sphere in the region but not beyond. Gauri was less well known here, but her activism on the Lingayat-Veerashaiva fracas attracted attention in Uttara Kannada and the surrounding regions in northern Karnataka and southern Maharashtra because it is also ground zero of the Lingayat/Veershaiva religion/caste (whatever you choose to call it). From Sharana Siddarama of Solapur, one of the prophets of the religion, to former Lok Sabha Speaker Shivraj Patil, the area has produced many prominent Lingayats.

That the finger of suspicion pointed to Sanatan Sanstha was hardly surprising. Four Sanstha activists — with Interpol red-corner notices against their names for their alleged involvement in a bomb blast in Madgaon, Goa in 2009 — were already on the lam at the time the serial assassinations of the rationalist-leftists began. One of them was Praveen Limkar. Under questioning, Naveen Kumar aka Hotte Manja named Limkar as the man he liaised with, leading the SIT to name him as the second accused in Gauri’s murder.

There were still many dots to be connected and much more evidence to be gathered but within weeks of Gauri’s killing, the Sanstha was already on the defensive. In an extraordinary press conference on 21 September 2017, the organisation preemptively challenged the investigative path the SIT was on. ‘It is claimed that the modus operandi in the case is similar to that of Dhabolkar and Pansare. What is the basis for ruling out the possibility of someone else using the similar strategy? Great uproar is being caused over the murder of Gauri, but what about the murders of Hindu activists like Chittaranjan and Thimappa Naik?’ asked the Sanstha’s Chethan Rajhans.

The organisation even rolled out its lawyers on the occasion— one of them, Sanjay Punalekar, arguing that some Sanstha members may be absconding from the law because they were afraid of being wrongly accused in cases. In all, five Sanstha members had been missing even before Gauri’s murder as agencies in Maharashtra investigated the Dabholkar–Pansare murders: Praveen Limkar, thirty-four, from Kolhapur; Jayaprakash alias Anna, forty-five, from Mangalore; Sarang Akolkar, thirty-eight, from Pune; Rudra Patil, thirty-seven, from Sangli and Vinay Pawar, thirty-two, from Satara. Were they the same men involved in the Kalburgi–Gauri Lankesh killings?

It was a curious press conference — defensive, tetchy, and an ideological counterpunch to what was primarily a criminal investigation by the SIT. ‘There were ideological differences between the Hindu activists and the leftists. But we have fought the ideological battle with ideology and have taken the legal route in a democratic fashion. We are ready for any kind of probe in this connection,’ the Sanstha challenged in a statement, lashing out at unnamed (but obviously Congress) politicians for ‘trying to gain mileage by defaming the Hindutva organization’. The refrain that the SIT under the Congress government was trying to frame ‘Hindu youth’ in Gauri Lankesh’s murder with an eye to the upcoming election would soon become the formal BJP line.

Meanwhile, Hegde eventually backed off from his remarks on the constitution and apologised to those whose sentiments he had hurt, with the usual protestation that his remarks had been misconstrued or distorted. But you could see where this was going. The words secular and socialist had been added to the description of India through the controversial forty-second amendment in 1976, changing it from just a ‘sovereign democratic republic’ to a ‘sovereign, socialist, secular democratic republic’. It is one of the foundational principles of the Indian Union. Indeed, the Indian ethos itself is based on the principle of ‘vasudhaiva kutumbakam’, the world is one family. Efforts to undermine and dismantle its secular character have now begun in right earnest, the socialist dream having already been substantially whittled down at the altar of liberalisation and globalisation in the early 1990s.

Back in our growing up years, Gauri and I rarely, if ever, discussed the Constitution. The subject was dry, and part of the civics and political science class, which our syllabus in high school and preuniversity did not include, because we were part of the science stream, with physics, chemistry and biology of greater interest to us (the latter two in the truest sense!). We took our rights, freedoms and liberties for granted. Constitutional issues and amendments were for law students to mull over.

Of course, the Constitution is not set in stone, least of all the Indian Constitution, which has been amended 123 times (in comparison, the US Constitution has been amended only twenty-seven times in some 240 years). But until recently at least, one did not think there were people in India who would like to subvert the Constitution (or ‘amend’ it, to put it tactfully) to turn India into a Hinduised Pakistan, a country whose Constitution is a travesty. No one in recent times had so brazenly proposed a fundamental change to one of the founding ideals of the nation. But now, communalism, exclusivism and otherising were being given official sanction. In Hegdespeak, if you were secular, or of mixed heritage, you were impure.

Read more: SIT files first chargesheet in Gauri Lankesh murder case

Such developments agitated Gauri Lankesh. Alone among our peers — most of whom were, and continue to be, unconcerned or indifferent to such developments — she recognised the growing communalisation early and warned against it several times. I read and watched from the United States, where similar nativist sentiments were being unleashed as white nationalist extremists repeatedly pitched an anti-immigrant agenda with the unsubtle support of a presidential candidate who was backed by many Hindutva mugs. In fact, there was a surreal similarity between some of the developments in the two countries. For every Hindutva hardliner in India, there was a white nationalist racist in America spewing the toxic rhetoric of the insecure, disguised as concern for a majority that was ostensibly being marginalised in its own country.