Essay: Partition and the inheritance of loss

Memories of the great forced migration and violence that accompanied Independence persist even in later generations that did not experience the events firsthand

On a pleasant evening in March 1940, poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz and his friend IK Gujral, who would go on to become Prime Minister of India, sat in Lahore’s Minto Park listening to Jinnah’s Lahore Resolution, a declaration for a sovereign Pakistan. “Never. Never did we think we would come [from Pakistan to India],” said Gujral when asked about the Partition and the subsequent uprooting from the West to East.

In Changing Homelands (2011), Neeti Nair, professor of history at the University of Virginia, documents the interviews she conducted in Delhi between November 2002 and August 2003 with former refugees and survivors of the Partition riots. Gujral was one of her subjects.

She asked survivors about their pre-Partition lives, their homes, neighbours, family and the violence they experienced in 1947. In the initial interviews, she often chipped in with insights but soon stopped because she believed it interfered with what interviewees had to say. At times, her questions were met with silence. “I listened carefully, for what goes unspoken is sometimes as important as what is said,” she says. Sometimes, her subjects asked her to turn off the tape recorder.

Caution: Recording is on

Last year, I sat down with my grandmother to listen to her experience. Born in 1944 in Rawalpindi, she had faint memories of her time on the other side of the border. I thought her story ought to be documented. The septuagenarian, who otherwise isn’t too fond of long conversations, obliged.

“They came to us. The Muslims. And asked us to leave Pakistan and go to India. This was July 1947 when clashes weren’t as intense. They were concerned. They didn’t want any harm to come to us,” my grandmother said. Even after the family was uprooted – they left their home, furniture and belongings behind – she thought they’d return in 15 days, once the riots ended. “It’s been 75 years now,” she sighed.

Now, when I think back to that conversation, I am overwhelmed by guilt. Was I profiting off her trauma, I wonder, and had I justified it to myself by saying that it was for the “higher purpose” of “documenting history”? Though I gave my grandmother whatever remuneration I got for the essay I wrote that used her experience, I still cannot shake off the idea that I was possibly driven by a voyeuristic impulse. I also worry that I retraumatised her by making her recall the anxiety and pain of being uprooted as a child.

Resolving the trauma

As is the case with any psychologically scarring historical event, survivors pass on their trauma to future generations. Perhaps my guilt too is a result of generational trauma. Sadly, there is little discourse on the mental health impact of the event on immediate survivors, let alone on subsequent generations.

Nair believes the word “trauma” is used too lightly. “The generation that experienced 1947 did not, as a rule, share their experiences of forced migration with their children,” she says. “They wanted to move on, make a living, forget the violence as best as they could”.

Her observation rings true given the many challenges the refugees faced and their urgency to make a living for themselves and their families. Perhaps, forgetting the violence was their way of moving forward.

Confronting history

In The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (2017), author and publisher Urvashi Butalia writes in great detail about the Partition violence. She echoes Nair’s observation that survivors wanted to forget as best they could.

“I realized that there was a way in which we feared these histories, and we did not want to confront them because sometimes we were too close to them, or our families and loved ones were involved, and also because confronting those histories meant admitting that we too had been complicit,” she says. “In the violence of Partition there were no clear aggressors and victims, so we have to admit that the violence was not only limited to the other side, but also came from us”.

She believes it is convenient to blame politicians and politics; for India to blame Jinnah and Pakistanis and for Pakistan to blame Nehru and Indians for what transpired. “But when you look at what people did, you see that there are no simple explanations. The perpetrators of violence were Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and others. And equally the peacemakers, those who helped people, who gave them shelter, came from all communities”. A possible starting point when it comes to confronting the trauma of Partition is to accept this.

Butalia also talks at length about the rape and abduction of women: the violence was perpetrated “not only by men of the ‘other’ community but also men of our own communities, they too raped women, they killed them claiming they were doing it for the community’s honour”.

Transgenerational ramifications

Nair believes that it wasn’t until the 1984 Sikh pogrom that repressed memories of Partition surfaced in survivors. “The first generation of feminists and anthropologists who interviewed Partition survivors – Urvashi Butalia, Kamla Bhasin, Veena Das – began asking questions of Partition violence only after their experience in the camps that were established in the wake of 1984,” she says. The refrain “This is like Partition all over again” made historians ask pertinent questions about the earlier trauma.

“Sadly there has been no public recognition of the psychological impact, nor any way to address it, although there are plenty of examples of such exercises to deal with traumatic histories across the world,” says Butalia who believes that trauma is passed down through generations in different ways. “A grandparent who has lived through violence passes down the sense of violation to their children and grandchildren,” she says.

She credits Sanjeev Jain and Alok Sarin, the authors of The Psychological Impact of the Partition of India (2018) for documenting the breakdown of medical services in 1947 and the prevalence of psychological distress in marginalized groups.

That breakdown has been reflected in fiction, most notably in Saadat Hasan Manto’s Toba Tek Singh (1955) based on a Sikh man being transferred from a Lahore mental asylum to one in India. He refuses to go, lying in the no man’s land between the barbed wire fences. “There, behind barbed wire, was Hindustan. Here, behind the same kind of barbed wire, was Pakistan. In between, on that piece of ground that had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.”

Toba Tek Singh, Bapsi Sidhwa’s Cracking India (1988) and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) all address the feeling of displacement, both on the physical and spiritual plane, which survivors experienced once they settled in refugee camps.

Unlocking repressed memories

Historian Salil Misra looks at pre-Partition communal politics in A Narrative of Communal Politics: Uttar Pradesh, 1937-1939 (2001) and investigates the conflicting influences on Muslims in UP, a state which was not divided but did play a key role in deciding India’s fate. “The minds of the people in pre-Partition India were under the influences of multiple ideologies. Sometimes, these influences were contradictory to each other,” he writes, adding that he wanted to see the impact of contrary influences on minds. “An entire generation went into silence over Partition. But silence is not the same as amnesia. Silence is a conscious act of suppressing one’s own memories when one is not able to come to terms with their own trauma,” says the professor of history at Ambedkar University. He believes those who had violence inflicted on them are still living with the psychological scars. “Silence cannot erase history,” he says.

Systematic denial of history is probably counterproductive. But why is the psychological impact of the cataclysm not a part of mainstream discourse? Why isn’t there enough research on the subject?

“Much of the intellectual academic energy was consumed by studies on what led to Partition rather than its impact,” says Misra adding that the focus in the post-Independence period was more on power structures, ideologies and important events.

It’s been more than 75 years and many of those who were displaced are now reaching the end of their lifespans. It wouldn’t be erroneous, however, to say that later generations, who did not witness the Partition firsthand, carry inherited memories.

“Generations that did not experience the displacement, transition and subsequent rehabilitation still carry memories which may contain prejudices and biases,” Misra says. “People who come from Partition families, never quite forget it. Even the newer generations. We need to find appropriate ways in which we can remember the past and store a bundle of memories, which may be euphoric or traumatizing,” he says.

The inheritance of silence

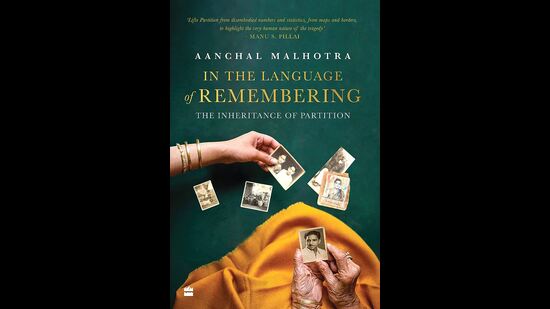

Aanchal Malhotra documented close to 130 testimonies of descendants of Partition displaced families from across the subcontinent and the diaspora in her mammoth In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition (2022). She explored how Partition continues to impact future generations, psychologically, and sometimes even through inherited silence.

“The younger generation may pick up the remnant activities of their ancestors, which arose due to sudden and traumatic migration— a small example is the hoarding of food or other items. I’ve recorded stories where descendants recall their parents or grandparents never wasting any resources — be it buttons, threads, or clothes repurposed several times— as the survival of Partition often led to frugality in many people. Some stories revealed how survivors slept with a knife under their pillow, due to the fear of what they had witnessed.” Malhotra thinks younger generations view Partition through the lens of their family’s experience and the related emotions evoked. “Similar to the survivor, they can be angry, compassionate or hopeful,” she says.

“Intergenerational transference of memories and grief happens over a period of time. Not everyone may feel the trauma. The transmission of such stories from one generation to another transfers the pain,” she says recounting that an interviewee’s grandmother had lost a child during the riots. When she found out about it, the interviewee had felt part of that loss even though it had been decades since the incident. “Memory doesn’t stop,” Malhotra says.

Faiz and IK Gujral, one a poet, the other a Prime Minister, have moved on, but the grief that transcends generations still endures.

Deepansh Duggal writes on art and culture. He tweets at Deepansh75.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website