Essay: On Greta Gerwig’s movie adaptation of Little Women

The sixth movie adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (first published in 1868), which released commercially on 25 December, incorporates contemporary feminist terms and expressions

The sixth movie adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women had its worldwide premiere at New York’s Museum of Modern Art on 7 December 2019, releasing commercially on 25 December, 2019. Wikipedia reports that as of 5 January, 2020 it had grossed $80.4 million globally and a recent NPR survey indicates its continuing global appeal in diverse formats: seven television adaptations of Little Women between 1939 and 1970 and four TV adaptations since, including two animated versions on Japanese television, a Broadway play in 1912, a ballet in 1969, an opera in 1998, and a Broadway musical in 2005.

Little Women was first published in 1868, its sequel Good Wives a year later. In 1880, the two novels were republished as one though they continued to appear separately as well. Alcott published a third book in the series, Little Men (1871), while the fourth and last (Jo’s Boys) appeared in 1886. The four March sisters Margaret (Meg), Josephine (Jo), Elizabeth (Beth), and Amy are the little women who begin the first novel and the title denotes the conflicted period between girlhood and womanhood, something both the book and its recent movie adaptation highlight.

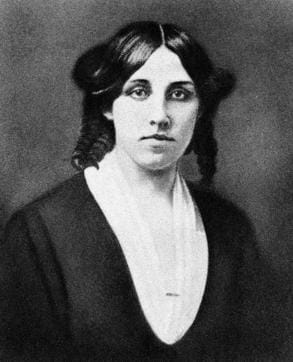

In its own time, Little Women was a runaway success. Building on the story of her own family, Alcott produced fiction grounded in the real world, foregrounding women without patronizing them. While domesticity remained central to her women’s lives, Alcott gave them a space within their daily grind and suggested that women need not be constrained by their limited choices. The idea that women could do something with their lives besides marry was new to America even though in another continent Jane Austen, the Bronte sisters, and George Eliot had already debated these issues. Greta Gerwig’s recent film mentions the Brontës just as it incorporates contemporary feminist terms and expressions into its script, but in Alcott’s own time the choices allowed women were few and far from easy. Jo’s would-be publisher Dashwood is categorical about not allowing spinsters in his publications: a woman would have to be married, or dead. Dashwood mirrors the generally accepted view of the time, and the hotheaded, outspoken, impetuous, independent-minded Jo March who says she will never marry is easily the most radical of Alcott’s women. Jo has often been seen as Alcott’s alter ego – in the latest movie version she is even cast as the author of Little Women.

A reviewer has pointed out how Little Women was marketed as “A Very Charming Book For Girls” in the Chicago Tribune’s classifieds, promising something “fresh, sparkling, natural, and full of soul.” This early marketing puff was undoubtedly the work of Alcott’s publisher but she acknowledges her own complicity when she says elsewhere in her writing that she could not have afforded to starve on praise. Gerwig has cleverly plucked out this statement and given it to Jo March in the movie, thereby pinpointing the universal dilemma (more acute than ever today) of an artist in a market-driven world. This detail is worth mentioning because, as the feminist perspective evolved, Little Women was critiqued for valorizing values considered “womanly”. Yet, as feminist critics acknowledged, Alcott’s work was revolutionary precisely because it did not falsify her social context but worked through her heroines to voice her principal concerns.

Marmee (Mrs March), in many ways the proverbial “Angel in the House”, is factual about her failings and the temper she has struggled to control all her life. She ably supports her family during her husband’s absence, stressing the importance of charity, compassion, community service, simple living, and independent thought. “Never let the sun go down on your anger”, she cautions Jo – a phrase that impacted me in my own tempestuous girlhood, remaining stuck in my head all these years. Meg is clear that she wants marriage, her own home, domesticity. Gerwig uses such statements skillfully in the movie to indicate the shifts in the feminist perspective, the acknowledgment that freedom implies choices and that these choices can never be absolute. Under her direction Alcott’s self-effacing Beth becomes a presence whose expressive face reveals a great deal about her silences. But Amy is the real surprise, Gerwig transforming the seemingly vain, spoilt and petulant youngest sister into a mature realist, a facet hinted at in Alcott’s novel but unambiguously evident here.

Gerwig combines the novel’s 19th-century context with a contemporary perspective that allows subtle, relevant additions to the script. Friedrich Bhaer, whom Jo marries, is off to California because they are more welcoming of immigrants, while a black woman at a community centre tells Marmee brusquely that the Civil War has not changed what’s bad in the country. But not all Gerwig’s adaptations work satisfactorily, as happens with both Friedrich Bhaer and Laurie (the boy next door whom Amy marries). Alcott saw the shabby, unkempt and older Friedrich Bhaer as Jo’s soulmate because he went against the romantic grain, a viewpoint ignored by Gerwig whose Bhaer is undeniably handsome, quizzical and just “foreign” enough to sweep any woman off her feet. The handsome playboy Laurie never ages and lacks the dashing flamboyance and evolving maturity of Alcott’s original.

Read more: Feminist retellings of Hindu myth: Return of the Devi

Gerwig has been deservedly commended for adapting a beloved book not merely because it is beloved but because she has found in it something to say. She begins her movie midway, with Jo poised outside Dashwood’s door for the first time and follows this dramatic, unexpected opening with back and forth movements between the original fictional plot. It’s a move that has been severally lauded but one cannot help seeing it also as constraining the movie’s accessibility to global audiences. Contrary to what the Anglo-American world may assume, most of the human race did not grow up reading Little Women. While Gerwig’s method imparts a refreshing tempo to the plot it could prove an unfortunate stumbling block to the uninitiated.

Vrinda Nabar is the author of “Caste as Woman” and a former Chair of English, Mumbai University.