Dev Anand’s Guide: Raju ban gaya transcendental man

In Dev Anand’s centenary week, an examination of why Guide, his film based on the novel by RK Narayan, is an enduring classic

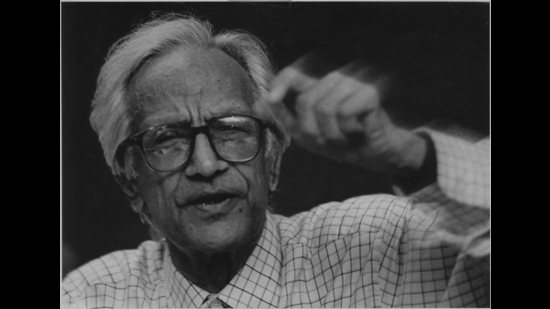

“Somebody suggested a book called The Guide, I had not read it but felt curious. So I went to Foyles the largest bookstore in London and asked for the book. They did not have any copy left, but the sales girl at the counter promised me she would procure one for me, if I left my address in London with her, which I did. The very next day, the receptionist at the Londonderry hotel called to say she was sending a parcel up to my room. I opened it to find The Guide waiting to be devoured by me. I read it at one go, sitting on the balcony of my suite, which overlooked Hyde Park. I thought it had a good story, and the character of Raju, the guide, was quite extraordinary,” writes Dev Anand in his autobiography Romancing with Life.

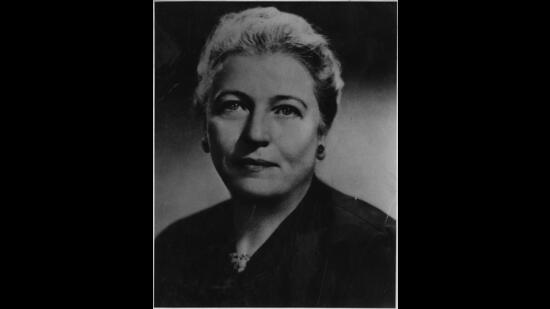

Excited by what he had read, Dev Anand immediately telephoned Pearl Buck in the United States. A visa was quickly arranged for him to meet creative partners Buck and Tad Danielewski in New York. Later, he met RK Narayan in Bangalore. Had it not been for that unknown someone who recommended the book, the film featuring Raju, an extraordinary protagonist, would never have been made.

In this, his centenary week, it’s easy to see why the character appealed to Dev Anand. Unlike other film stars in the India of the 1950s and 1960s, he did not shy away from playing characters with shades of grey, those on the fringes of society. In Taxi Driver (1954), he was the man behind the wheel; he was a gambler in Baazi (1951), a gangster in House No 44 (1955), and a bus conductor, who loses his job and is compelled to make a living as a black marketeer of movie tickets in Kala Bazaar (1960). Drawing inspiration from Hollywood’s noir cinema, he fashioned the original Indian rebel hero, one who is neither anti-hero nor tragic protagonist nor the usual brave and virtuous leading man. His rebel heroes were self-centered nonconformists who were not conventionally brave. They were also unruly though never ungentlemanly. Dev Anand’s distinctive acting and his understanding of layered characterization made him the prototypical desi rebel hero.

Raju, the guide, was fashioned in this mould.

The Indo-American production was to be filmed simultaneously in Hindi and English with Buck collaborating on the script and Anand starring in both versions. Chetan Anand, the eldest of the Anand brothers and an established filmmaker at that point, agreed to direct. However “a clash of creative egos” (writes Anand) between Chetan and Tad Denielewski led to Vijay Anand coming on board as director.

The Hindi version rolled out once the English one was completed. The latter, which was directed by Danielewski, sank without a trace. 58 years later, Guide, the Hindi film is an enduring classic. Released in 1965 when India was still a young nation focussed on modernization and on building its public institutions, it tells the story of two unusual characters who meet and fall for each other in circumstances not so ideal. Anand’s glib, self-promoting tour guide, Raju, can chat up anyone. Waheeda Rehman plays Rosie, a devdasi-turned-classical artiste now called Kumari Nalini (her name change indicating, perhaps, a move from the decadence of her original profession to the purity associated with “Nalini”, the lotus). Then there is Marco (Kishore Sahu), Rosie’s archaeologist husband who offers her a “socially acceptable identity” through marriage. But Rosie and Marco’s conjugal life is troubled and they do not share an emotional bond.

Guide could well have been a typical triangular love story with a well-defined hero, heroine and villain, but it chose to be utterly different. Unlike Dev Anand’s earlier films, all the three main characters are flawed. While Raju undergoes a transformative arc from non-yielding to an achiever, who is deceptive and possessive, and finally, to a man on the path of renunciation, Rosie is tainted in her marriage of convenience and later in her inability to understand Raju’s complex character. Marco also falters, only to later regret the loss of Rosie. Flawed too are the supporting characters of Raju’s mother, uncle, and his dear friend Gafoor, who represent traditional Indian society that views women from unconventional backgrounds as unacceptable.

The film was ahead of its time in many ways. Raju and Rosie decide to live together despite social pressure. They exude a defiance that was unthinkable in the India of that period. Pertinently, the country legally recognised live-in-relationships between consenting adults only as late as 2010.

Early on in the film, the splendour of Udaipur is highlighted in the song sequence Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tamanna Hai. The grand past of the location is established as the nourishing ground of love even as the story is set firmly in the impoverished present of India of the immediate post-colonial period. Raju’s modest home, the rickety car that initially ferries the couple, and the rural scenes in the second half are all realistic.

Raju restores Rosie’s self-esteem; he also mediates for others including the hapless villagers stuck in underdevelopment and hit by devastating drought. He helps the village get its first post office, school and hospital, a direct intertwining with a developing India. In keeping with the spirit of that age, Raju’s character is a self-styled reformer. Indeed, things are great until he forges Rosie’s signature. He is punished by the law and by the filmmaker, who then lets his protagonist immerse himself in correctional discourse via the spiritual route. In the end, he is accepted by everyone including those from whom he was estranged – his mother, Rosie and Gafoor.

A script like Guide, based on paradoxically-paired plot points working constantly towards building up characters and then sabotaging them thereby enhancing cinematic tension, would be unthinkable in 2023. Love and heartbreak, riches and renunciation, a fulfilled, joyous life and then seeing it messed up and destroyed – Guide honestly allows for the concurrent existence of moral flaws and virtue. Sadly, this sort of layered characterisation is not a staple of current filmmaking. Today, filmmakers do not opt for paradoxical paired themes packaged allegorically. And the climax cannot be a scene of redemption with a song that signs off with Allah megh de, panni de, chhaya de re, Rama megh de, Shama megh de.

Perhaps it is the utter impossibility of remaking it in the current era coupled with the ability to enjoy and recognise its originality that makes Guide an enduring classic.

Nilosree Biswas is an author, filmmaker, columnist who writes about history, culture, food and cinema of South Asia, Asia and its diaspora.