Bhuchung D Sonam - “Human experience is as deep as it is vast”

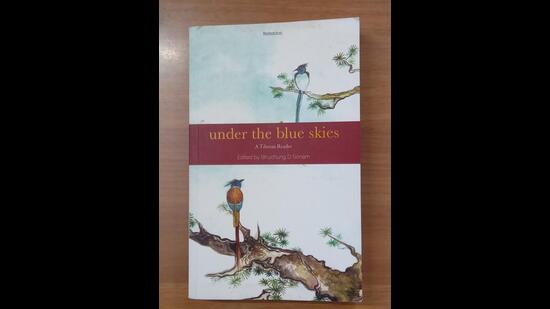

Dharamsala-based Tibetan poet, translator and publisher Bhuchung D Sonam talks about the role of literature in the Tibetan freedom struggle and about editing Under the Blue Skies: A Tibetan Reader, an anthology of fiction, poetry and non-fiction

How do you view the role of literature in the Tibetan freedom struggle?

Acts of storytelling are crucial for a small exiled community such as ours because we are fighting against Chinese colonial power that has a humongous state propaganda machinery continuously churning out untruths. Literature also deepens our sense of identity and connection since Tibetan refugees are scattered around the world.

Your book Under the Blue Skies: A Tibetan Reader aims to offer “a fresh and an alternative window to the individual and collective Tibetan psyche”. What kind of stereotypical or jaded representations are you looking to challenge? Whom do you hold responsible for the way in which Tibetans have been represented in literature?

For many centuries Tibet and the Tibetan people have been written about by outsiders. Although Tibet has a very rich repository of Buddhist literature, we did not invest much in producing secular literature based on human experience. There are a lot of misperceptions about us which are a consequence of writings done by others, primarily Western travellers, missionaries, diplomats and fantasy-seekers.

Since we were forced into exile in the aftermath of China’s occupation of Tibet, Tibetans have started to write in English and other languages. Today, there is a new generation of Tibetans who have linguistic skills to articulate their deepest thoughts and opinions. As a result, non-Tibetans have access to Tibetan writing, which is based on lived experience and hence free of stereotypes.

Tell us about the fresh and alternative voices and perspectives that you have chosen to highlight. What sets them apart from earlier writing? How did you find them?

My own writing, and in fact writings of most contemporary Tibetan writers, are based on our first-hand experience as people who are forced into the space of others. We write about loss, anger, frustration, loneliness as well as hope that things will change for the better. A new generation of Tibetan writers like Lekey S Leidecker, Kaysang, Tenphun and others have unique voices reflecting their realities. There is a generation of Tibetans attuned to the tenet that, as Kaysang writes, “Living does not mean not dying” and, as Tenphun writes, “Tibetans who have a small store of Hindi vocabulary siphoned off from barmaids, taxi drivers and barbers”. Their lives are, as Kalsang Yangzom writes, “an intersection of many selves, pilgrimage to an ancestral home, India or Tibet?”

The Own Voices movement in literature draws attention to the importance of authentic representation and marginalised people taking control of their narratives but also gets criticised for limiting the scope of literature by telling writers that they should stick to writing about their lived experience and not appropriate other people’s stories. What do you think?

I think human experience is as deep as it is vast. With any writer from any community, particularly those who are/have been historically marginalised, exploring his/her own innermost thoughts, wisdom and silence, the story is bound to be unique to his/her own self/community. When a person honestly articulates his or her deepest emotions, they will echo universal human sentiments.

The question of appropriation arises when people I call “story-hunting tricksters” travel to remote places spawning exotic tales spiced up with mysticism and their own preconceived ideas, and then sell these tales as original stories or accounts of a people and a culture they didn’t even try to understand. This has happened to many marginalised communities, including Tibetans.

The book has three sections: fiction, poetry and non-fiction. What made you decide on this structure instead of grouping writers based on the subjects they write about?

Although we have been writing and producing works of literature for several decades in exile, there hasn’t been an anthology containing all three categories in one title. I thought it would be both useful and interesting for outsiders to have Tibetan fiction, poetry and non-fiction in a single edition – a kind of an entryway to the world of Tibetan literature. The other, and perhaps more important, reason was that Under the Blue Skies was to be a supplementary textbook in Tibetan refugee schools, where the students have always been taught Indian and foreign literature in English. How wonderful it would be if Tibetan children are introduced to and taught Tibetan writing in English!

Given the stature and the popularity of the Dalai Lama, several non-Tibetans assume that most Tibetans are Buddhist and the diversity is often overlooked. In the process of putting together Under the Blue Skies, did you seek out Muslim, Christian, atheist and agnostic voices from the Tibetan community? What were the challenges that you faced?

It was the Fifth Dalai Lama in the seventeenth century who granted a site in Tibet’s capital city for the Muslims, who were mostly a merchant community, to build the first mosque. There is also a small number of Tibetan Christians in eastern Tibet. As far as I know, there has never been interreligious disharmony in Tibet although we had witnessed disputes within the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism. In exile, the Dalai Lama has played a crucial role in the survival of the Tibetan struggle as well as continuation of its culture and spiritual traditions. His charisma and visionary leadership are recognised throughout the world, and consequently Tibet is viewed through this lens.

I am not aware of Tibetan Muslim or Christian writers who produce secular literature, which was what I was looking for in Under the Blue Skies. Tibet and its people have been typecast, by and large, through a Buddhist perspective, which is not an entirely accurate representation of Tibet. The country has many different shades, some of them are subtle and yet important. Therefore, I wanted the anthology to be free from religious didactics and prevalent stereotypes.

The book is published by Blackneck Books, an imprint of TibetWrites. How does your publishing model work? Is it based on grant funding or does it depend entirely on book sales?

We have an advisory group of prominent Tibetan writers, who read sample chapters of our proposed titles. Based on their advice and feedback, we make our publication decisions. TibetWrites operates entirely on a voluntary basis. None of us get paid for what we do. Our primary goal is to promote secular creative Tibetan writing. We do get some funding for our publication projects from The Tibet Fund.

What similarities and differences do you notice between creative writing among the Tibetan diaspora living in India, Bhutan, Nepal, USA, Canada, and other countries?

I am neither a scholar nor have I done any research or studied literature for that matter, and therefore I am not in a firm position to comment on this. But some common themes displayed in their writings are exile, loss, hope and an uncertain sense of identity as they are forced to negotiate two or sometimes even more social, political and cultural realities in their daily lives.

Tenphun, who was born in Tibet and grew up in exile, writes:“I forgot my roots / I wish, I only wish to go back to my childhood sailing paper boat”. Lekey Leidecker, born and raised in the West, writes: “in a long history of using / brown people at convenience / I recite Tibetan phrases / foreign to my English-immersed tongue as theirs, / At a local Quaker meeting”. Tenzing Rigdol, born in Nepal, grew up in India and living in USA, writes:“When I wake up, / May I find all my past to be / Just a dream – / A poetic error, A bad handwriting / A terrible comedy”.Their writings are as different as their backgrounds, and yet a deep sense of dislocation and out-of-placeness bind them.

Being an editor of an anthology is an entirely different experience from being a poet. What do you love most about both these roles?

I like to read and write. Editing is working with words, and writing is playing with words. Editing maybe a little more logical and writing more emotional, but both are fundamentally the same vocation.

Tell us about the other projects that you are working on.

Blackneck Books published four titles last year, a novel in Tibetan called Murder of Tenzin, a non-fiction book called The Tragedy of the Modom House and two volumes of poetry – Carrying Memories and Learning Tibetan. We have two titles to be published in 2024 — a memoir and a book of poems. We have offers for a Hindi anthology of Tibetan poetry and a Spanish one too. We will have to see how they go. Otherwise, we receive proposals for individual poems that people want to translate into other languages. These are mainly for online publications and sometimes for magazines as well.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.