Aruna Roy – “The demonising of activists is unfortunate for the nation”

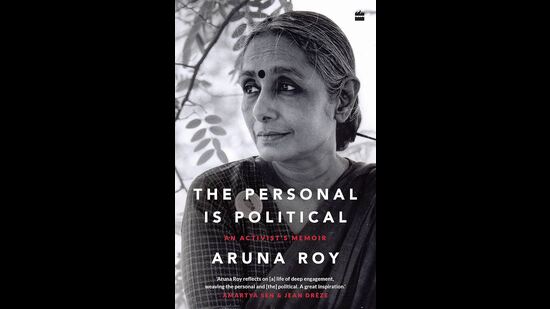

The author of The Personal is Political; An Activist’s Memoir on the role of people’s movements in a democracy, the shift towards neo-liberalism within the civil service, and attempts to impede the RTI Act

Why did you choose “The Personal is Political” as the title for your memoir?

My life and work have been inspired and defined by this feminist slogan. When Harper Collins asked for a title, it seemed the best one for a memoir of the life of an activist, or anyone in public life. There is a continuing conversation between two parts of a human being, the personal and the political, as all engagement with public action is set in an ethical, constitutional and democratic frame. It’s a truth that all women and females understand from birth that our lives are a battle for equality. It is a part of the female consciousness and existence – at home and in the world outside.

Becoming an IAS officer is a dream for many but in 1975 you decided to resign. What pushed you to take this step?

Many of us who appeared for the civil service exams, did so because we had a commitment to work for people who were less privileged. The IAS was seen as a “service”, with sufficient power to enable us to realise our dreams. But in actual fact, once I entered the mechanisms of governance, I began to see the multiple frustrations of an individual trapped to a great degree in the hierarchy, opaqueness, corruption and lack of accountability of the system. The older systems of patronage still managed to dominate many parts of life – postings, foreign scholarships, and in those days, UN postings et al. I had joined to work for the poor, and that was only partly in focus. I knew it needs continuity and constant transfers do not help finish a job we begin. To add to it all, I was in a cadre like the UT, spread all over the country. After seven years, I decided to go where I could work without hierarchy, fight corruption and the arbitrary use of power with independence and continuity, while using the law and the constitution for people trapped in multiple layers of oppression.

How do you assess changes in the civil services since you were a part of it?

The civil service has been transformed into what is commonly derided as the “Indian Avatar Service”, or some such equivalent. The people may not see or hear the head of the district administration, except rarely. The newer demands of obliging senior politicians and bosses keeps junior officers busy and unable to go to the people. There have been exceptional civil servants who have managed to keep people’s faith alive – like the famous late SR Sankaran of the Andhra Cadre. When he passed away, civil servants rubbed shoulders with people’s movements and all political parties assembled together to say goodbye to a great Indian. SR Sankaran, unfortunately, remained a member of an exceptional and exclusive group of committed officers. The current orientation of civil servants is markedly different from olden days. From addressing poverty as the principal concern and therefore prioritising welfare, the emphasis now is on “progress” and the neo-liberal agenda. The vocabulary of “roti, kapda, makaan” may be used but on ground there is a sharp change that’s reflected in unprecedented unemployment and increasing unaccountable practices. The constitutional values of equality, justice and secularism are also under threat.

The big gap between promise and delivery of welfare services was the cutting edge of concerns for the poor. It became the overwhelming concern of all of us who began working with the underprivileged and those who were discriminated against. We worked with alternative development design and participatory policy making against petty corruption, and battled with endemic hunger, access to justice, and the right to life and livelihood.

What role do movements play in a democratic country?

A democracy has to be run collectively through systems of representation and consultation. The fact that we elect our heads of government and continue to do so gives us the implicit right to monitor them from the time they enter the public domain. It begins from their nomination, through their election, assuming office, and subsequently, delivering promises. This demands the establishment of platforms to critique and question, suggest policy and law, to address people’s problems, and later, to go through the process right up to parliament through parliamentary standing committees, ensuring that people’s voices are heard. In the process of stating their claims/ rights to people’s constitutional rights and policy, the movements use struggle, engagement with government, forming campaigns, and thereby creating pressure to ensure that the country is being run participatively in the interest of the large majority of electors at the margins. Their presence and inclusion in governance systems are vital to the health of a democracy.

In the present socio-political context where both activism and activists have been incessantly demonised by people sitting on constitutional posts, how can they rebuild trust among communities and move ahead?

When governments use autocratic processes, are non-inclusive and unaccountable, and evolve policies which vitiate basic constitutional rights and the voices of activists and activism – in fact, of people genuinely interested in their own betterment – become a threat to unaccountable power. The demonising of activism and activists is very unfortunate for the health of a nation. It is vital in a democracy that there is freedom of speech and there are means to constantly question lack of transparency and accountability, and to resist threats in the form of the arbitrary use of power.

The first unconstitutional and undemocratic act is to create a narrative of the nature of public action, and demonise activists and their work. It lays the ground for the incarceration and victimisation of people who, with non-violent tools of struggle, place a critique of power in the form of their issues before the system. In other words, those who speak truth to power. Their voices can only be suppressed by the misuse of democratic methods and systems.

Do you feel RTI has evolved as you wanted it to? What changes can be brought in to make it better?

The RTI is and remains a powerful legal tool to question the state and its performance. From the smallest to the biggest issues of state policy, decision making and implementation, the RTI continues to bring the discourse to matters of constitutional justice.

There needs to be implementation of the RTI first, before we ask for changes. For instance, the RTI begins with either an application or with suo moto disclosure under section 4. Except for the governments of Rajasthan and Karnataka, who have websites like the Jan Soochna portal and Mahiti Kanaja respectively, the rest of the governments are still in denial mode about addressing the issue. Unless we know what the government is doing, how can our questions trace the inadequate delivery of justice, rights and needs?

The current regime, since its initiation in 2014, has been trying to slaughter the RTI Act. They did it initially with the amendments to the Act, which were introduced covertly disregarding the Central government’s Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy. It is regressive and seeks to weaken the autonomy of the information commission, raising significant concerns. And later on, with the introduction of the DPDP Act, posing a threat by proposing a legal framework where the central government exercises complete control over information. It is expansive in scope, impractically large in scale, authoritarian in its oversight, and arbitrary in its application. The RTI Act strikes a balance between transparency and the right to privacy through its exemption clause under section 8(1)(j). This delicate equilibrium would be disrupted by the DPDP Act, which not only overrides the RTI Act but also utilises the right to privacy as a rationale to conceal the utilisation or misuse of public resources by identifiable individuals, including public officials.

Since you have extensively worked with farmers and the working class, how do you see climate change affecting them? Is enough being done to safeguard their rights?

They are the worst sufferers of climate change, and yet, they are the ones who prevent the large-scale devastation of natural resources and the planet from destruction. The MGNREGA, for instance, provides workers with a right to live in a way in which they strengthen the environment. The priority of their work plans, so far, is to strengthen rainwater harvesting, preserve soil, and for the better part, use human energy to conserve nature. The government at the centre has been hostile to the law for the last 10 years. The West Bengal Government has suffered the most from non-release of funds, but the steady shrinking of budget outlays to a programme, which gives crores of people the right to live with dignity and work, and preserve the environment, has affected workers everywhere.

In an India that was looking towards self-sufficiency, the highest issue on the list was food security. Production of our own food and grain requirements is a fundamental part of the sovereignty of a nation. If that is in any way destroyed, like with the farm laws, it is suicide. Independence and national hyperbole have no meaning if we have to depend on imports. That gives scope for international blackmail if ever we are in a position of large-scale drought or hunger, and climate-impacted disasters. This critique has been in existence since the 1980s.

The Farmers Movement proves, both, the need for people’s movements and the fact that without food sovereignty, without self-sufficiency in basic economic needs, freedom stands threatened.

Chittajit Mitra (he/him) is a queer writer, translator and editor from Allahabad. He is co-founder of RAQS, an organization working on gender, sexuality and mental health.