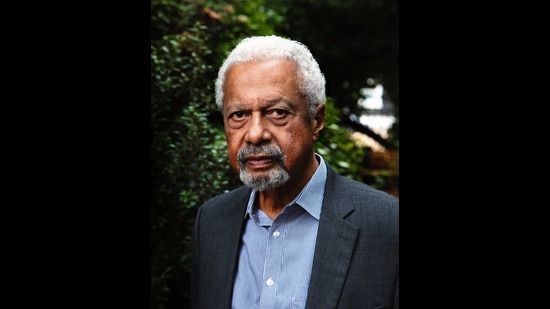

Abdulrazak Gurnah: “Silence can also be vocal”

On dramatic irony in his writing, Chekhov’s gun, how tourism blights smaller places, and ‘Theft’, his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize in 2021

In your novel, By the Sea, there’s this fragment, “it seems as if one life has ended and I am now living another one”. In the context of your Nobel win, does it seem like a new beginning?

No, it doesn’t feel like a new life. It has obviously made a big difference in how much time I have to write or to do whatever other things I might wish to do. For me, the most important thing about the Nobel award was the recognition. Everybody knows about it — even people who don’t read. But for a writer, it is something very definite. That is to say, your writing is okay. The prize is given once a year and even for just one year, to be told something like that is very reassuring.

In addition, there is, of course, the interest that it generates in readers. They want to know about the work, the person. The translations follow. People want to meet you, you get invited, travel, etc. For a writer, you can’t wish for something better than to have your work transmitted in this way. But it does take time. It does take time.

Your works are full of silences pregnant with meaning.

Silences come in different forms and as a consequence or as a response to different kinds of pressures. For powerless people, I think silence is more or less the last resort to retain their dignity. If you know you do not have the power, as it were, to reply or to refuse, then in a sense, silence is all that’s possible. To say, okay, you can do what you like because you have the power to do it, but I’m not going to defer to you, then silence is also a means of holding on to the dignity of the self.

Silence is also a disagreement. It could be something somebody says to you and you don’t want to get into an argument, so you keep quiet. It’s also a means of offering a response. Silence can also be, in this sense, vocal. It’s saying, I don’t agree. And there is something disconcerting, particularly against the bullies and groups, about silence. [For example, they get confused.] Why aren’t you angry? Why aren’t you showing some sign? So, it can be a way of demonstrating that power isn’t all-powerful; power can be resisted. Children do it all the time. They tell you, no, I’m not happy with what you’re doing by doing nothing, saying nothing.

Critical Perspectives on Abdulrazak Gurnah by Tina Steiner and Maria Olaussen (2013) notes that your “fiction asks the reader to consider stories as provisional accounts that cannot claim closure or complete knowledge even when narrators tell their own stories”. This sits well with your latest, Theft, where, despite operating with limited knowledge, the characters narrate their lives as if they know everything.

This is a very old technique. Sometimes you imagine that you’re watching a play. The figures in the play don’t know something that the previous scene has already told the audience. So the audience knows much more than the people actually on the stage doing their business.

Dramatic irony, that is. The same kind of technique really works in fiction. You have some information. Of course, there is more because a practised reader will probably start speculating things. And then that’s part of the interest of both reading and writing. It’s not a contest, but it’s part of the pleasure of it. And then if something unexpected happens, you say, I didn’t see that coming.

So, all of these are ways in which the tension of the story in fiction works. Otherwise, you’re just going to have a kind of like a synopsis. This is what it’s about. This is what happens. But this way [with dramatic irony] you engage with the movement of the events and you engage with the people themselves — the characters, the figures, because they too are discovering as you are discovering. And so, I think it’s part of the pleasure of reading.

I wanted to touch on that aspect because, as you said, seasoned readers can sense what is to come. For example, when Karim, in the beginning, says that he won’t become a typical father figure, you know to expect something later. Seeing what they anticipate come true, do readers gain pleasure, is the ego massaged, or are they disappointed by “predictability?”

It’s part of the pleasure of reading. It’s not ego. It’s like when you say, I knew it was going to be like that. You don’t want that to be too obvious, though. Because if the signals are too strong, there’s no “God, I know what you’re going to do.” You know, this very famous comment that Chekhov is said to have made — if a gun appears in Act One of a play, then you know, it’s going to be used. So there’s going to be a death somewhere a little further on. Depending on whether you’re a practised reader or otherwise, you see something more, possibly or possibly not.

Except for Fauzia, one can sense absentee father figures in this book. Was it something you were purposely trying to do given that there’s also a peppering of Oedipal signals throughout the book?

Well, it’s really the two boys — Karim and Badar. One does not know his parents, his mother or his father, his actual parents, that is, although he’s brought up by people. Whereas the other one is, in a sense, brought up by his grandmother and then by his stepbrother, finds a mother again. And so, although the father is absent, there is a network of support. There are varieties of ways in which these children, as they grow up, are orphaned or, in the case of Fauzia, not orphaned.

And I think it’s not unlikely that you might find a real difference between people’s experiences of parents and domestic support. But my idea was to have somebody who is indeed powerless and who does not have that network of support still has to make his way in life in some way, and how does he do that? Where does he find the resources to do that? Somebody like Karim is going to be all right because he does have a network. Somebody like Fauzia will also have that, but here’s somebody who doesn’t (Badar). So, I put those three together to see what they deal with, what life has dealt to them, and how they cope with what life has dealt to them.

Leaving, which is one of the themes of the novel, is seldom a voluntary movement. Several factors influence this decision. Were you trying to say something about the nature of power and its effect on others?

To a certain extent, this is true for most of us as we go through, particularly at a certain age, when you’re not in control or you have control to some extent, but not entirely. In the case of Badar, of course, he says, once again, his life has changed without any decision on his part, which is exactly to demonstrate just how powerless he is. He has no control. He cannot make decisions. Decisions are made for him. Well, at least not at that stage.

Of course, later, he is able to make decisions. So, it’s not just about leaving. It’s also about other people being able to make decisions, like where will you go and what you will do. And he is not the one who’s doing so. Even Karim is somebody who says, come to Zanzibar with me and I will help you. So, it’s still other people directing his life at this stage.

A few reviews note that you’re critiquing the growth of the tourism industry in Zanzibar in Theft. Was it intentional or do you think it was where the story could naturally go given Badar’s background?

Tourism is a complex thing for a small country. For a prosperous country, tourism is something completely different from tourism for a small country like Zanzibar. For example, maybe for India, it’s a different situation. But for a small country, it can have a terrific, transforming impact. Of course, in some respects its impact is positive. It brings work; possibly a certain kind of calmness because the government has to behave itself. It can’t go around being too authoritarian. Otherwise, the tourists won’t come. The pavements get fixed. The water is available, etc. These are the positives.

But the other side of it is that it also brings a kind of corruption of the customary social practices of a place. Something new comes, something very powerful — lots of money, different ways of living, different ideas about what constitutes propriety and so on. And it corrupts those who should know better. Those who should be making decisions now take money to enable certain things that they should say no to. For example, no, it’s not in our interest to allow you to make that a private beach; no, it’s not in our interest to allow you to knock down this part of town in order to build a hotel, and so on. But they take a commission and say, yeah, OK, do it. I’m saying this is exacerbated and made worse in a small place, whereas in a bigger place, it can be absorbed in other ways. You can overcharge them, etc. It becomes something dominant and dominating and to some extent corrupting in a small place. Unfortunately, if a country is too dependent on tourism, then the resistance is also diminished. You have no choice but to accept whatever it is that the foreign money is demanding should be there.

Readers are sort of teased to discover a theft in your novel which also has several narrative arcs that signal theft. Was that why the novel’s title is Theft?

Of course. When I started, the central idea for me was the accusation of theft and the injustice of that. And again, as I’ve said, how does somebody like Badar without support, without family, without education, without anything really, a servant, how does he cope with such an accusation, which is unjust, but leads to his expulsion? But, as you said, there are different kinds of thefts — stolen childhood or the [Tamarind] hotel, which is a building stolen from an Indian family. Or, later, an accusation that’s made against Karim. So, there are also sorts of theft — beyond the theft of life but also of thefts of a physical nature, there are thefts of a global state. So, it seemed like a good title to me for the book.

Saurabh Sharma is a Delhi-based writer and freelance journalist. They can be found on Instagram/X: @writerly_life.