William Dalrymple’s visual tribute to a Mughal emperor who fought East India Co rule

The Historian’s Eye is an exhibition of photographs shot by author William Dalrymple as he researched Mughal emperor Shah Alam’s valiant battle against the East India Company for his new book, The Anarchy.

Three years ago, author William Dalrymple started a journey that took him around the length and breadth of the country and its borders. He was researching for his upcoming book, The Anarchy, which revolves around the East India Company, “a militarised multinational” which destroyed the mighty empire of the Mughals.

As Dalrymple writes in the introduction to his new exhibition at Mumbai’s Akara Art, organised jointly by photo gallery Tasveer and art platform Dauble, he was fascinated with how “a dangerously unregulated private company with one small office occupying less than two hundred yards of London street frontage — five windows wide” ended up seizing India at the end of the 18th century.

The central protagonist of The Anarchy is the Mughal king Shah Alam, a charismatic poet and courageous ruler who fought the East India Company’s military genius Robert Clive. In trying to retrace this period and walk in the steps of the king, the author visited places where history was made, and art and architecture thrived in the 18th century, including battlefields, Sufi shrines, temples, gardens, crumbling Mughal havelis, palaces and forts across India and Pakistan. Dalrymple also researched the culture of the period, be it the technique to make attar in Lucknow, or the art of painting miniatures in Kashmir and the lower Himalayan valleys of Chamba, Guler and Kangra.

A bygone era

“It is one of the most ignored periods in Indian history. This is despite the fact that so much of beautiful art and architecture was made in that era. Pahari miniature art was thriving,” says Dalrymple, adding, “There are also very few books on Shah Alam, despite the fact that he is such an interesting character.”

In the introduction, Dalrymple narrates how in the 1750s, Shah Alam broke out of his besieged mansion in Delhi and decided to head east to revive the fortunes of his dynasty, by ousting the British from Bengal. Without money or support, but largely thanks to his charisma, he managed to get people to join his caravan and form an army. However, in 1765, he was captured. He managed to escape and return to Delhi where he was brutally blinded by an Afghan warlord. In 1803, the British marched into Delhi claiming they are there to ‘protect’ the blind emperor, effectively marking the end of Mughal rule.

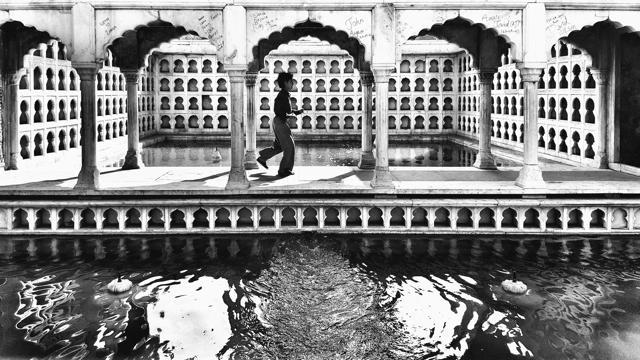

To document the historically significant places, Dalrymple shot black-and-white images using a Samsung Edge mobile phone camera and Snapseed cellphone app. “It (the camera) has a guerrilla nature to it. It allows you to click immediate, instant photographs. You can see something and just swoop in with the camera, which is kept in your back pocket,” he says. He admits, though, that there are certain disadvantages. “A high shutter speed means you cannot take action shots, it is also tough to take close-up images from afar. The images can’t be blown up either to a larger size print,” says Dalrymple.

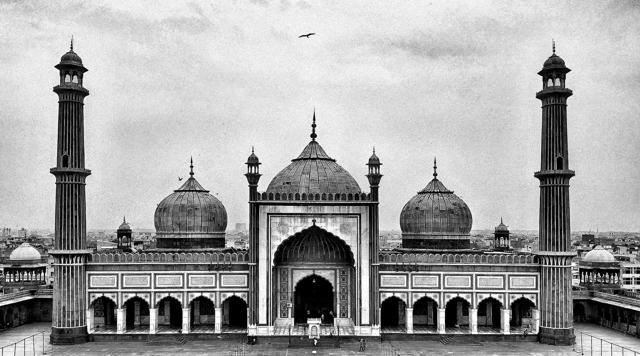

Around 40 of the images shot by him now feature in the exhibition, The Historian’s Eye. The grainy, haunting images depict the Red Fort and Jama Masjid in Delhi, the East India Company’s headquarters in Calcutta, the capital of the nawabs of Bengal in Murshidabad, and Tipu Sultan’s base of Srirangapatnam, among other sites.

In 2016, Dalrymple had released his first book of photographs, The Writer’s Eye, which was a collection of 60 black-and-white frames shot over 18 months, using a phone camera. While the approach was similar, Dalrymple says the research for this exhibition/book was more focused. “I specifically shot places that were significant in 18th and early 19th century Indian history,” he says.

Back to the roots

Dalrymple got interested in photography after he was gifted a Kodak camera for his seventh birthday. At age 15, he was left some money by a relative and he spent it on a Contax 35mm SLR. “For the next five years, I spent much of my time in the school darkroom, emerging after several hours stinking of fixer, with waterlogged hands, and developer splashed all over my clothes, but clutching a precious sheaf of 10 by 8 prints,” he recalls, in his introduction.

For Dalrymple, this book and exhibition offered a great opportunity to rediscover his roots in Bengal: primarily his Calcutta-born, part-Bengali great-great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron, who happens to be one of the first women photographers. “As a child in Scotland, I used to leaf through her portraits in the albums we had at home and envy the world she had created, and her ability to make such luminous and painterly portraits with a camera,” recalls Dalrymple.

For Dalrymple, shooting images in black and white has always been a conscious choice. “I have always preferred black and white, partly because it allowed me to develop and edit my own prints; but mainly because black and white seemed a much more daring and exciting world, full of artistic possibilities.”

After writing several books and exhibiting/publishing his photographs, Dalrymple has figured out the contrast between both mediums: “As a writer, you work and rework your prose, you polish and polish again, like a Mauryan sculptor polishing a yakshi, as you patiently try to cut your sentences down to their essence. Photography, in contrast, is a far more immediate and feline art form: often your best images are those that capture the fleeting moment. You whip out your camera and you seize something that may vanish in a second.”

What: The Historian’s Eye

Where: Akara Art, Churchill Chambers, 32 Mereweather Road, Colaba, Mumbai

Till when: From April 13 to May 3

Dalrymple’s book The Anarchy releases in 2019

Follow @htlifeandstyle for more