When it isn’t right to say cheese

Photographers have often pushed the envelope when it comes to shooting subjects that are taboo or disturbing. But what differentiates a thought-provoking image from one that’s in plain bad taste?

Those who believe there is no such thing as bad publicity would do well to learn from photographer Raj Shetye’s recent experience. In a series of photographs from a fashion shoot titled ‘The Wrong Turn’, Shetye shows a model dressed in designer clothes and wearing a near-deadpan expression being molested on a bus. As the online world, where Shetye had uploaded the images, erupted over the offending photographs, calling them a poor attempt at recreating the Delhi gang rape of December 16, Shetye was left with little choice but to remove the images. But not before shocked members from the photographers’ community had voiced their disapproval.

“Some people are not only insensitive and irresponsible, but also foolish. How anyone could have thought of doing something like this amazes me,” says photographer Raghu Rai. His feelings are shared by photographer Prashant Panjiar: “The question of artistic freedom and ethics cannot be confused with bad taste. I have freedom of speech. But does that mean I will stand on the road in front of schoolchildren and scream obscenities?”

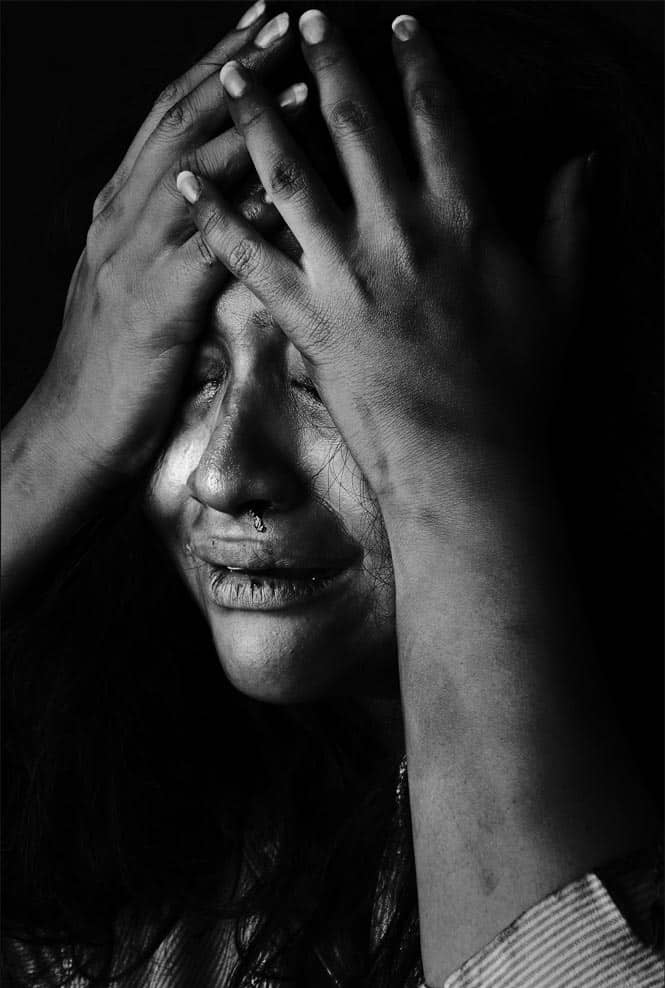

Actress Konkona Sen Sharma gives expression to Mukhtar Mai’s suffering in a series of photographs shot by Rafique Sayed.

The world of photography is no stranger to controversy. In 1975, photographer Garry Gross took a series of photographs of a naked 9-10-year-old Brooke Shields. The photographs were taken with the consent of Brooke’s mother Teri and were part of a project titled The Woman in the Child, where Gross reportedly wanted to show the feminity in prepubescent girls by comparing them to adult women. Brooke tried to stop further use of the photographs in 1981, but failed. While this would now be considered a case of child exploitation, things were different with actors like Pooja Bhatt and Mamata Kulkarni who caused much moral outrage in the India of the 1990s, by posing near-naked or with their bodies painted for magazine covers. “My way of testing whether an image is offensive is to see whether the woman being depicted in the image is a subject in her own right or if she is just another object, a recipient of whatever is happening around her,” says Kavita Krishnan, secretary, All India Progressive Women’s Association.

Women — whether in fashion or the news — are not the only subjects that demand sensitive representation. War, poverty, natural disasters and accidents have all fascinated photographers, often pushing them to capture that defining moment, often at the cost of sensitivity and good taste.

“In the aftermath of the Bangaldesh War of 1971, a group of photojournalists told the soldiers of the Mukti Bahini that they didn’t have any action pictures. The Mukti Bahini responded by unleashing atrocities on a few alleged Pakistani informers,who had been captured during the war. The photographers had their action images,” says Rai, adding, “Just a few days prior to this I had faced a similar choice. I had accompanied the first column of soldiers in the battle. After five days of risking my life, I still didn’t have any action images. The soldiers told me they had a member of the enemy side who was badly wounded and had little chance of survival. They offered to shoot him to give me the action I needed. I said no. If I do not have the power to prolong anyone’s life by even a few minutes, I have no right to shorten it either A photographer should never lose basic humanity.”

The lure to freeze a moment for eternity — and through those frames, live on forever — has got the better of many a photographer. In 1993, Kevin Carter photographed a malnourished toddler during the Sudan famine. The child had stopped to rest while crawling towards some food. Close behind the toddler waited a vulture. Though the image came to symbolise the suffering of the people in Sudan during the famine, helped raise funds for sufferers and won a Pulitzer, many expressed concern over the fate of the child and criticised Carter for not helping him. Some termed Carter “another predator”. While many would attempt a purely conscientious stance, Panjiar has a more reasonable approach.

Actress Konkona Sen Sharma gives expression to Mukhtar Mai’s suffering in a series of photographs shot by Rafique Sayed.

“There is no universal code of behaviour. Each situation is different. In a situation over which one has no control, the photographer has to decide whether there are other people to help a victim. If yes, it is the photographer’s job to bring to the world the realities of that situation in as sensitive a way as possible and by bringing it to the attention of others, hopefully, help bring about a change for the better,” he says. There is no universal guidebook for photographers, though most photography clubs or associations have a charter of ethics for members. The Indian Penal Code also has sections that refer to photography without permission and related crimes. However, most photographers agree that an image could be in poor taste, while not flouting the law. “I have a thumb rule. There are three stakeholders in any image – the person or society being photographed, the photographer himself or the space where the image will be exhibited and the viewer. One has to decide whether one is being true to all three.

If you are being dishonest to any one of the three, then the image is wrong,” says Panjiar. Sometimes, it would seem, photographs do lie. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attack, German photographer Thomas Hoepker, photographed a group of seemingly relaxed Americans with the burning twin towers in the background. The photograph that was published in 2006, made the subjects seem untouched by the tragedy. A man, who later identified himself as a member of the group, clarified that everyone in the picture were actually “in a profound state of shock and disbelief” and that the picture had been taken without permission. An image can be perfectly true, a straight representation of an event and still be profoundly disturbing as is Richard Drew’s “The Falling Man” another 9/11 image. The picture caught a man in what has been described as a ‘calm’ moment whilst falling from the tower.

So how can you tell if an image has gone too far? “One can shoot a photograph in the heat of the moment but must think before publishing it. How much horror does one show? Viewers today are more sensitive than before and one has to decide accordingly,” says Panjiar. Most would prefer to leave it to the photographer, and where the photographer errs, to the public. Anything is better than bringing in a draconian law or setting up an organised system of censorship. “Any shot may be done aesthetically. There is a thin line between sensuous, erotic and vulgar. Like any other artist, a photographer needs space to perform. But you also have to keep in mind your audience and what is acceptable to them,” says photographer Dabboo Ratnani. Where the photographer fails to make that distinction, Kavita Krishnan urges society to step in. “Protest”, she says, “but instead of vandalism, what we should do is contest these images with our progressive and emancipated ones.”

Maturity and an evolved ethical sense have a role to play. Where Shetye ended up, according to a viewer, “making rape look like fashion”, veteran photographer Rafique Sayed used the medium to depict the trauma of rape with a great deal of empathy. His pictures of actor Konkona Sen Sharma, while focusing solely on her expressions, manage to mobilise sympathy for the suffering of Mukhtar Mai, a Pakistani gang rape survivor. Here Sen Sharma isn’t just Mukhtar Mai. She is every woman who has been brutalised. Perhaps, empathy is the X factor that distinguishes good pictures from bad. Take Rahul Saharan’s images of acid attack victims posing like fashion models. “The idea was to be candid and to allow the girls to be themselves. The effect would have been different if I had got models to do the shoot. Make-up might have given them an appearance of being scarred, but I wouldn’t have been able to capture the emotions in their eyes,” he says. A picture can speak a thousand words; it is up to the photographer to choose the words that his pictures convey.

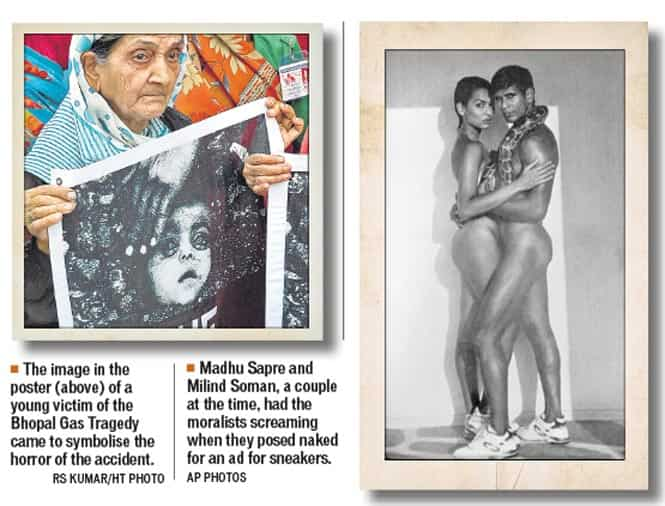

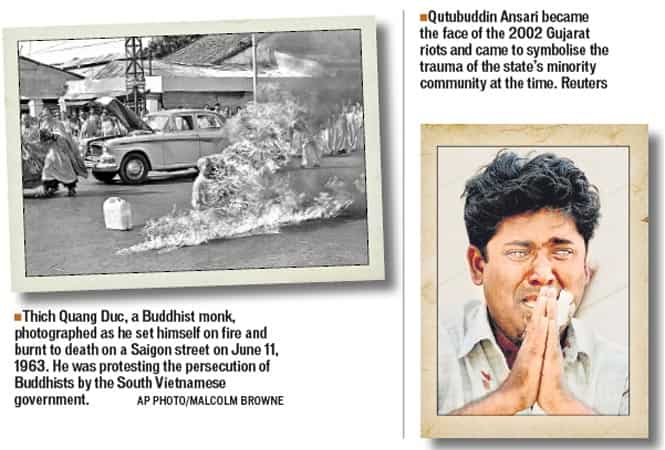

Freeze frame: pictures that sparked outrage

Expert views:

Touched by Mukhtar Mai’s experience: Rafique Sayed

There are some things that are just insensitive and in bad taste. I have been a fashion photographer for many years. Many people know me as a fashion photographer. But you cannot project social problems through a fashion shoot. A fashion shoot is unreal; it creates an illusion and you can’t use it to project a real problem like rape. Also, internationally, black and white is the preferred choice of medium while presenting a sensitive subject through photographs. I was deeply touched by Mukhtar Mai’s book — In The Name Of Honor — A Memoir. Mukhtar Mai, a woman from the village of Meerwala in Pakistani was gang raped by members of a local clan, as punishment for the alleged indiscretions of her brother. I wanted to raise my voice against crime against women by portraying her horror through photographs. I had never shot Konkona before. But I have never seen a woman express so well. I clicked those 200 to 400 photographs in just two hours.

Not just issues related to women, other subjects require sensitive handling too – a natural disaster or an accident, for example. I remember during a major accident, there had been a controversy over some photographs. People felt the photographer had given more importance to capturing the tragedy than to helping the victims. His argument was that he was a photographer and not an activist. But as a human being I would rather have tried to save a human life, even if that meant losing a great photo opportunity. Freedom is crucial for any artist. But freedom needs to be balanced with responsibility. I do not believe in setting boundaries for expression, but at the same time, a photographer needs to be aware.

(Rafique Sayed, Photographer)

Don’t like it, don’t see it: Atul Kasbekar

How does one decide the boundaries of what is acceptable? It varies from person to person and society to society. None of the fashion magazines that are acceptable in India would be acceptable in more conservative societies; in the Gulf countries, for example. I think it’s time we stop this protest over anything and everything, claiming insult to our sensibilities. Every time there is a big movie being released, someone will have something to protest about in it, whether it is Amir Khan’s poster in the upcoming film PK or something else.

If you have a problem with it, don’t see it. Who’s forcing you to? I think the courts should tell these people to stop wasting their time. I have been shooting fashion calendars for 13 years now and I think all my photographs treat women with utmost respect. The women look beautiful. If it doesn’t conform to somebody’s sensibilities, I can’t stop them from feeling the way they do.

(Atul Kasbekar, photographer)

Freeze frame: pictures that sparked outrage