Tour the British Museum’s massive Tantra exhibition in 10 objects

What was the philosophy? What was its impact? Sculptures, posters, paintings, thangkas and manuscripts — some dating to the 11th century — are among the 100 items on display.

A mega exhibition opens at London’s British Museum this autumn (September 24, 2020 to January 24, 2021) and it’s built around the Indian philosophy of Tantra, which grew in popularity between the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

“Tantra affirms all aspects of the material world as a manifestation of divine feminine power,” says Imma Ramos, curator of the medieval and south Asian collections of the museum and also curator of the exhibition. “It teaches that enlightenment can be achieved by actively engaging with spiritual obstacles such as desire, aversion and fear in order to ultimately transcend them.”

And so, some of the deities of Tantra took inspiration from gods of mainstream Hinduism, such as Bhairava -- a Bhairava sculpture from Tamil Nadu is actually part of the exhibition; this helped the philosophy appeal to people living on the fringes of Hindu society. Over time, with the emergence of Buddhism, it expanded to include elements from that religion as well.

Some of the exhibits in Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution can be viewed online at britishmuseum.org. Wknd went on a tour and has curated these 10 objects (painting, prints and sculptures) of interest from among the more than the 100 on display.

Housewives with Steak-Knives, collage

Artist Sutapa Biswas, 1985

The British artist overlays elements of the goddess with images of a contemporary Indian woman. This is not the ma of popular culture, but Ma Kali. “White men who are unfamiliar with the imagery are threatened by it,” the artist told The Guardian.

Untitled, acrylic on canvas

Artist Biren De, 1974

De is referred to as a Tantric painter and always denied he was one, so this is an interesting addition. His paintings from the ’70s do depict concentric shapes of mandalas framing luminous central deities. “For De, Tantra was expansion of consciousness. By making us acknowledge the fragmented state of our existence, our limitations, his art encourages us to transcend these barriers,” curator Ramos says.

Ramprasad Sen with the goddess Kali, print

Artist P Chakraborty, 20th century, Bengal

This print shows the goddess Kali as a revolutionary force shadowing Sen, an 18th-century Kali devotee/poet. It’s considered to be an early example of the country represented as the Motherland, and took on special significance amid the freedom struggle.

Bhairava sculpture, granite

11th century, Tamil Nadu

Bhairava is considered a reincarnation of Shiva (revered in Tantra philosophy for his delight in defying conventions and boundaries). Bhairava is believed to have emerged from Shiva’s nail which was used to chop off one of Brahma’s heads in order to cut the latter down to size. A scrap from a nail, growing so powerful is symbolic of the philosophy of Tantra.

Karaikkal Ammaiyar, bronze sculpture

Late 13th century

Karaikkal Ammaiyar was a 6th-century Tamil saint who abandoned her role of obedient wife and danced her way to the gods. It was this challenge to established hierarchies that appealed to the marginalised.

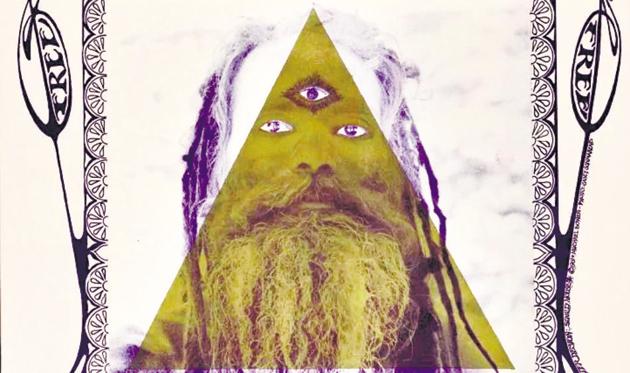

Human Be-in, poster

1967, USA

This poster designed by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley (photograph by Casey Sonnabend) advertises the Human Be-In festival, held in San Francisco, which heralded the Summer of Love. “Yoga and meditation were promoted as transformative practices that could inspire minds to challenge the status quo. The poster includes a portrait of a yogi taken in Nepal. Yogis captured the popular imagination in the West as countercultural role models,” the curator writes in the exhibition blog.

Saraha and the Other Mahasiddhas, thangka

18th century, Tibet

Saraha was one of the great Tantric masters, or mahasiddhas. Saraha wielding an arrow is symbolic of deep focus; the female arrow-smith is the mandatory tip of the hat to Shakti, the feminine power that underlines the philosophy.

Raktayamari and Vajravetali figures, bronze with turquoise, gold and pigment

16th to 17th century, Tibet

“Tantra is a compound of two words, tan, the body, and tor, meaning yours,” says Anuradha Ghosh, Tantric scholar and professor at Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi. This divine couple is intertwined, about to celebrate their bodies. The deeper Tantric thought of internalising both one’s masculine and feminine qualities or selves is also reflected. The Tantra philosophy of inclusivity would find echo, too, in today’s fight for the freedom to choose, and the freedom to love, led by the LGBTQI community.

Hatha yoga manuscript

Early 19th century

This page depicts the yogic body with a focus on the Kundalini, imagined as a serpent (representing power), coiled at the base of the spine. “Tantric yoga is routed through the arousal of cosmic energy, Kundalini Shakti,” says Madhu Khanna, chairperson of Tantra Foundation, New Delhi.

Aghoris, photographs

Dolf Hartsuiker, 1990s

The Aghoris, followers of Bhairava were taken by the Indophile Dutch traveller Dolf Hartsuiker. Aghoris typically worked in burial grounds; extracted metal during post-death rituals. Their practices tended to place them on the margins of society; their everyday life was one of busting taboos.