Akbar’s Delhi: Tracing the Mughal ruler’s legacy in monuments

Shazi Zaman, author of an upcoming Hindi novel on Akbar, takes us on a walking tour of some of the sites associated with the Mughal emperor in Delhi.

We are inside the stony ramparts of Purana Qila, staring at the steeply-cut steps visible inside the short, squat tower of Sher Mandal. It is here, while climbing down this very flight of stairs of his library, that Mughal emperor Humayun fell to his death.

That fateful winter evening in 1556 gave the Mughal empire its new king: thirteen-year-old Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar, who was crowned in Kalanaur.

It’s a story that we have heard before. But standing at the site and hearing it from Shazi Zaman, the author of a soon-to-be released Hindi novel on Akbar, is to make corporeal the ghosts of history books.

Zaman is a born story-teller. They slip off his tongue with ease -- historical details, little-known facts and, what draws you in, actively imagining what went on in the heads of people dead and gone more than 400 years ago.

Though Akbar is more closely associated with Fatehpur Sikri, the capital he founded in Agra, there are places in Delhi where parts of his story still live.

“Delhi was too powerful for Akbar to ignore it and Akbar was too powerful for Delhi to ignore him,” says Zaman.

A veteran journalist and a history student, Zaman has lived with the character of Akbar for the last 20 years, researching, reading primary sources, culling incidents and anecdotes.

“Did you know that Akbar was an accomplished Braj bhasha poet?” asks Zaman. “He had a flair for languages. He loved to coin new words. For example, he came up with the word ‘Shishshobha’ for the headgear worn by kings.”

If Zaman’s fascination for his subject is an indicator, the novel, published by Raj Kamal Prakshan and to be released later this month, promises to be a worthy read. In the eight years he spent writing the novel, Zaman consciously stayed away from all fiction related to the Mughal emperor – including the 2008 film, Jodha Akbar. “When I finally submitted the manuscript, I felt such an emptiness, like I had nothing to do,” he laughs.

Just across from the Purana Qila is the Khairal Manazil mosque. “Very few people know that an assassination attempt was made on Akbar’s life from the first floor of this mosque in 1564,” recounts Zaman.

A miniature in Akbarnama, Abu’l Fazl’s chronicle of Akbar’s reign, captures the scene: The king on horseback, clutching the arrow; his retainers in hot pursuit of the would-be assassin, killing him.

The bazaar of the miniature is now a straight road. We cross it, open the padlock of the mosque and walk in. This mosque, and a madrassa attached to it, was built by Akbar’s wet nurse Maham Anga who wielded considerable power in the court. A few devotees still offer namaz here, drawing water from the well for their wuzu. It’s a picture of flinty calm, with no hint of the ancient intrigue.

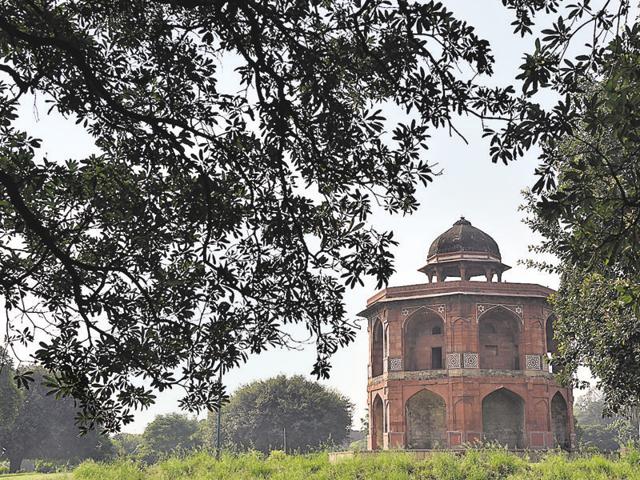

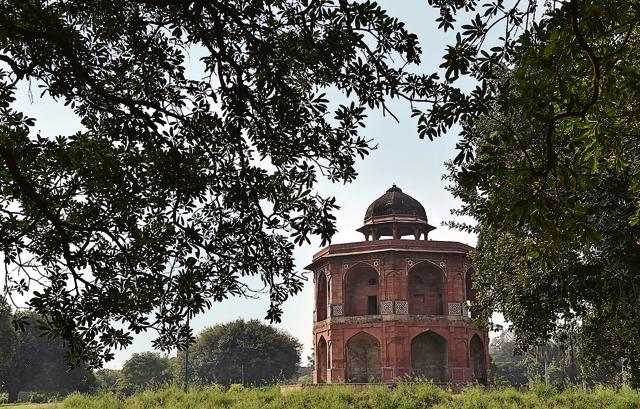

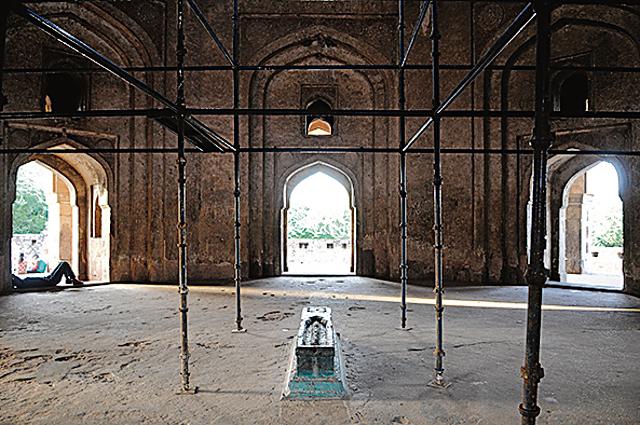

The history of two of the other Delhi monuments associated with Akbar is also clouded by murder and revenge – the tombs of Atagah Khan, Akbar’s general and Adham Khan, Maham Anga’s son and the man behind Atagah’s murder.

But more than the political conspiracies and Machiavellian power plays, what fascinates Zaman were the king’s spiritual battles.

“I was very keen to explore Akbar’s deep spiritual anxiety, his religious curiosity and his desire to bring multiple streams of faith together,” says Zaman.

Akbar’s abiding love for Sufi orders, his mysticism, his preoccupation with faith are all well-documented. Kings over the course of history have appropriated divinity, but the embattled Akbar stands out, racked by spiritual dilemmas, obsessed with the idea of a perfect faith.

“He thought of himself as a spiritual guide of the people, not merely a worldly emperor,” says Zaman.

An episode from 1578 forms the crux of Zaman’s novel. The king was camped on the banks of Jhelum in Punjab when he experienced what many say was a mystical vision. Zaman chanced upon a Rajasthani account of a courtier who was beside the king when the vision occurred. This was a turning point in Akbar’s personal history, from where his grappling with religion took a decisive turn.

This kingly quest towards spiritual awakening culminated in Akbar’s founding of Din-e-Ilahi, a new order which combined aspects of Hinduism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Jainism among others.

“But he never forced any one to follow Din-e-Ilahi,” says Zaman. Those who did, laid down their head gear on the emperor’s feet as a mark of submission. Those who didn’t, such as Man Singh, an important courtier and related to Akbar by marriage, continued to enjoy the king’s patronage.

“Tansen wrote about the emperor, Dillipati tum nabi ji ke naib ati sundar sultan,” says Zaman. As our walk winds up, it is this Akbar that hovers over our morning.

What: IHC walk on ‘Akbar’s Delhi’, led by author and journalist Shazi Zaman

Where: Register at IHC programme desk. Call 24682002

When: 8 am, October 23