For the record: Gen Z is taking to oral history

Young adults committed to recording the everyday on devices and social media are finding common cause with the Oral History Association of India, whose online sessions have seen record-high numbers in recent months.

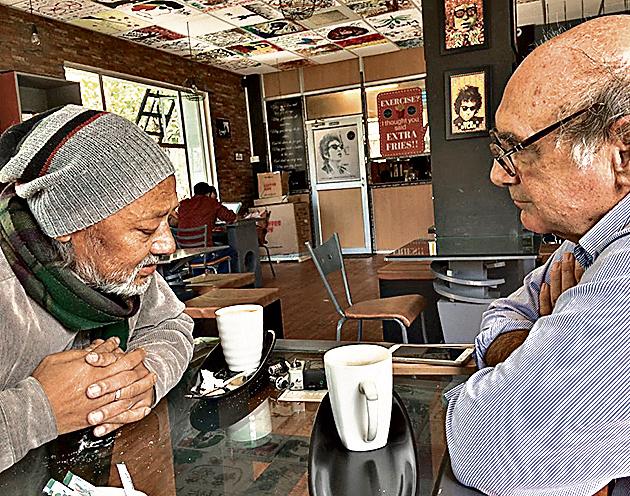

To the digital recorder, Vincent Stone talked about his father, John Stone, the army intelligence man. Vincent, a businessman in his 50s, had stopped at a cafe in Shillong in 2017, to narrate the story of his dad, a music teacher who gave up that life to join the Indian army in the ’60s.

In 1968, he called his family to say he was returning home. Then he vanished without a trace. Through the narration, Vincent barely looked up at oral historians Indira Chowdhury and Alessandro Portelli. He had clearly waited years to get his story out.

It eventually appeared as a blog post by Chowdhury and Portelli, on theoralhistorian.com.

With the world in a tailspin, oral histories have never seemed more urgent. For self-preservation. To add to collective memory. And to make sense of who we were, how we got here, and where it could all be headed.

“Oral history works on recording, presenting and interpreting the voices of those who are often not included in mainstream history. This is about preserving an alternative public history,” says Chowdhury who teaches at the Centre for Public History of the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru. She is one of the founders of the Oral History Association of India (OHAI), set up in 2013.

In the pandemic, a new generation has been logging on. As OHAI moved all its activities online, in October, its Zoom workshop, Starting Your Oral History Project, was overbooked. Over 90 people — most of them students — signed up, and OHAI had to conduct two workshops instead of one.

This was followed by two public lectures, again well attended, on Zoom and Facebook. The themes here were how Partition touched the lives of ordinary people, conducted by OHAI member and author Saaz Aggarwal, and oral histories of the Narmada struggle, conducted by current OHAI president Nandini Oza, 55, a writer and archivist.

OHAI members include chief archivist of the Godrej Archives Vrunda Pathare; Surajit Sarkar, associate professor at the Centre for Community Knowledge, Ambedkar University, Delhi; and Pramod Kumar Srivastava, retired professor of Western history at Lucknow University.

If it seems surprising that Gen Z would be interested in oral histories, it might help to think of them as public histories instead. And, in that sense, it is easy to see why the OHAI mission resonates with a generation committed to recording the everyday in real time — on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube.

So, is any person willing to tell their story automatically an oral historian? “While personal memoirs and diaries can be a rich historical source, these do not fall under oral histories as here, an interviewer is absent. In oral history, the interviewer or oral historian is an integral and an important part of the process,” Oza says.

A core skill for all oral historians to develop is the ability to listen without judgement, to probe with the right questions. “For example, when someone says ‘my first salary was Rs 100 per month’, ask gently or curiously, how much did bread cost in those days, or what was the rent for your home. And you might learn that the Rs 100 was a respectable sum back then,” says author Saaz Aggarwal, 59, who has recorded the oral histories of Sindhis and is an OHAI member.

The biggest give-backs of oral historians is that business histories and other institutional histories could be a new social history and throw new light in the making of modern India. At OHAI conferences, Pathare who is also secretary, OHAI, has talked of her independent oral history work at Godrej.

“While corporate oral histories provide insights into responses of employees to changes in policies, processes, office culture etc., sports also emerges as an essential part of office culture in the 70s and 80s and employees’ participation as a part of ‘the Godrej team’ in various sports tournaments including cricket tournaments such as the Thane Vaibhav Tournament that helped create a sense of belonging,” she says.

What are the histories that OHAI hopes young people will record? S Bharat, 29, an OHAI member and an archivist at the French Institute of Pondicherry, says young historians should find interesting ways of “capturing the contemporary moment”.

“We are at a major point of transition. There is so much social upheaval. There are stories and conversations, such as those of the migrants, that need to be caught so that they don’t fall through the cracks when we try to tell larger narratives of the nation,” he adds.

Bharat, a volunteer since July, joined OHAI in December. “I joined because I felt it was important for practitioners to come together in a space that can give rise to collaborative work,” he says. “Archiving can be lonely work. You can’t just work in isolation.”