Building cultural bridges from Iran to India

The Qand-e-Farsi wa Tutiyan-e-Hind exhibition in Delhi shows that books, and knowledge, were steady items of exchange between both civilisations.

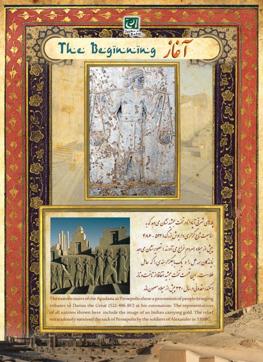

Due to the imperial policy of Darius I (522–486 BC), a great king of Iran, Persian was once upon a time the most spoken language in the world. Darius ruled over approximately 50 million people, i.e, at least 44 percent of the world population. The land across the Indus, or parts of ‘India’, is supposed to have been part of his territory ruled by his satraps. But this claim has been contested by Indian scholars. What is, however, undeniable is that trade and culture united the two civilisations .

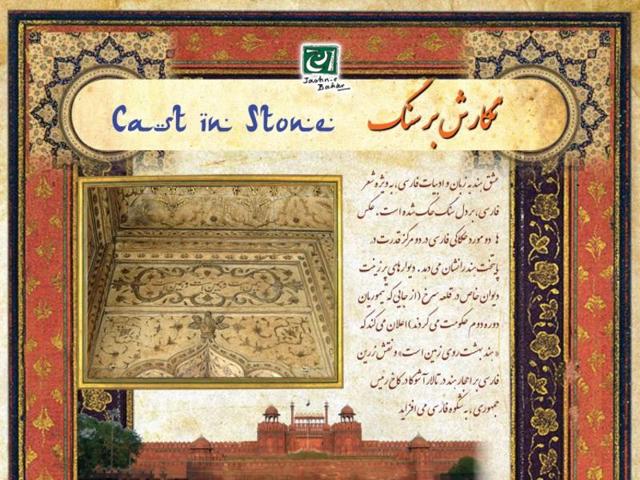

An interesting exhibition, Qand-e-Farsi wa Tutiyan-e-Hind (Of Persian Candy and Indian Parrots), with aesthetically curated panels, shows that books, and knowledge, were steady items of exchange between both. These books were not some nondescript titles but the big books of India – the Panchantantra, Ramayana and the Mahabharata – that inspired works of literature everywhere.

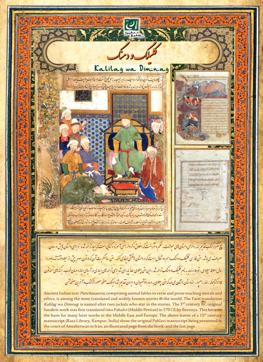

“Panchatantra was one of the major inspirations behind Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book,” says well-known Urdu aficionado Kamna Prasad, who has curated the exhibition. So was the Kalila wa Dimnag, a re-telling of the Panchatantra by Borzuya, a physician of another great Iranian king, Ḵosrow I, also called Anusherwan.

It is believed that Borzuya wrangled an India trip out of Anusherwan by saying that the land had nectar which he would get for his king. Instead, he returned with the Pañchatantra -- he translated it from Sanskrit to Persian -- and it became the book kings and emperors would dip into to know how to run an empire.

“Kalila wa Dimnag, of course, did not give directions to kings. You couldn’t tell a king directly what to do except in a roundabout way,” adds Prasad. One of the exhibition’s panels shows the manuscript being presented in the court of Anusherwan. The artwork used in the exhibition uses photographs and facsimiles of original manuscripts available in libraries and collections across the world.

Under Mughal emperor Akbar, the traffic between Persian and Sanskrit was two-way and rich. The emperor started a bureau of translation works in Fatehpur Sikri and ordered several Persian manuscripts to be translated into Sanskrit. He also entrusted linguists to translate Latin, Hindi, Sanskrit and Greek books into Persian. “Todar Mal, Akbar’s revenue minister, maintained land documents in Farsi,” points out Prasad. In 1582, Akbar organised the translation of the Mahabharata and sent copies of it as gifts to his noblemen.

From Sufi-musician-scholar Amir Khusrau in the 13th century and Bedil Azimabadi in the 17th; to Mirza Ghalib in the 18th and Muhammad Iqbal in the 20th century, the confluence of culture between India and Iran has been robust. To sum up: this may have been a relationship driven by kings but it was the playground and a mine of cultural riches for our artists.

At: Main Art Gallery, Kamladevi Block, IIC, till October 1