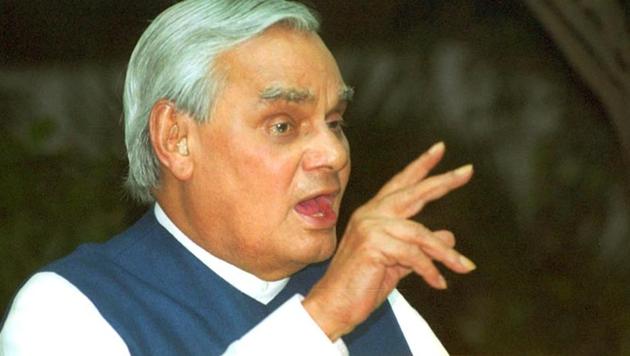

There was something in Vajpayee that marked him out as his own person

He would think and plan and strategise as part of the saffron family. But he would feel, empathise with, smile, lament and – most importantly – share the silence of reflection with those outside the saffron family, no less than with those within it

No one chooses to be born. Much less to this or that family, community, country. No one has any hand in the fall of that dice.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, born on this day in 1924 in any clime, culture would have been shaped by that environment, moulded by its mores. But being the kind of person he turned out to be, he would have imbibed something, rejected something else, modified, turned around influences and pressures and become – himself.

Something in him, something unique to him, would have made him, wherever he was, to be his own maker – poet, friend, politician, statesman. If born a Christian Indian – and on this Christmas day – he would have related to the New Testament as a poet would. But he would have found the Old Testament impossible reading. And the Book of Genesis would have sent him to sleep, as it did young Mohandas Gandhi. As a Christian, he would not have enjoyed the company of proselytising missionaries but would have loved men of the Church like CF Andrews, Verrier Elwin and Jerome De Souza.

Had he been born to Islamic parents anywhere in India he would have been inclined by temperament, instinct and taste to Sufi poetry, music. His mind would have resonated to the insights of Jalaluddin Rumi, the character of Dara Shukoh, the poetry of Mirza Ghalib. The rugged veracity of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan would have touched his heart, the lyrical intellect of Maulana Abul Kalam, his mind. He would have opposed the partition of India. The use of Islam’s great name for acts of violence, terror would have appalled him. For Khuda’s sake… he would have said… the Holy Quran does not enjoin this.

The wings of destiny brought Atal Bihari Vajpayee to a Hindu hearth in the deepest recesses of Hindu life in small time Batukeshwar and then Gwalior, at the core of Hindi and Hindu pride. In his school teacher father and home-caring mother he had quintessential Hindus, saturating him in Hindu epics, and a sense of the greatness of Hindu dharma. As a result Atal Bihari Vajpayee was an unswerving member of the Sangh Parivar.

And yet there was something in him that marked him out as his own person. He would think and plan and strategise as part of the saffron family. But he would feel, empathise with, smile, lament and – most importantly – share the silence of reflection with those outside the saffron family, no less than with those within it.

I have two personal experiences of the Vajpayee who was ‘himself’, who could touch a chord with someone with a mental chemistry wholly different from those of his ‘parivar’.

The first is about a signature of his. Aware of the text of his stirring obituary tribute to Jawaharlal Nehru, I sought and got through the kindness of his secretary, Shakti Sinha, on March 7, 2000, his autograph on a typescript of that speech. That autograph of a prime minister, a BJP prime minister, on the text of his tribute to India’s first prime minister who has been the BJP’s bete noire is among my cherished possessions.

The second is about a comment, or a set of comments of his. In April, 2002, as High Commissioner for India to Sri Lanka – a position to which he had appointed me – I was in Delhi to ‘cover’ a visit by President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. Riot-burnt Gujarat was still smouldering. At a lunch in Prime Minister Vajpayee’s official residence on April 24, 2002, she asked her host “What is the situation in Gujarat like? Have there been deaths ?” Vajpayee requested Advani to respond. The deputy prime minister gave the visitor details – about 800 dead as on date, of which 180 he said were due to police firing. At this Vajpayee made just one comment: “Gandhi’s Gujarat”. I could see eyes turning towards where I was seated – at the table’s farthest end.

“Did you hear that, Gopal?” , President Kumaratunga said to me. “The prime minister says ‘Gandhi’s Gujarat’.”

“Yes, I heard”.

Could Vajpayee have said more? Perhaps, yes. But to a visiting head of State? Perhaps, no. In that wisp of an incomplete line… “Gandhi’s Gujarat”… the prime minister of India said it all.

The lunch gave over, as we filed past the PM to say goodbye, he said to me “Gopalji, Gujarat jal raha hai”. (Gujarat is burning). “Agar vahan kuchh karne ke liye ap mujhe adesh dein, to mein tayar hun”, I said. (If you direct me to do something there, I’m ready). He heard me in silence.

That silence of his was him. Gujarat was burning. And so was he.

A human flame burned for breath inside the sealed glass-chamber of his political role, longing to be – himself.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi is distinguished professor of history and politics, Ashoka University

The views expressed are personal