The inside story: How New Delhi charted its diplomatic win in Kargil

Atal Behari Vajpayee, Jaswant Singh, Brajesh Mishra and K Raghunath played an exemplary role during the crisis

Once the Indian political establishment, led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, became aware of the extent of Pakistan’s Kargil intrusion in 1999, it resolved to end it — if possible, without enlarging the conflict. Military and diplomatic elements of national power were brought into play in flawless coordination to achieve the objective. The splendid work of India’s defence forces has attracted great attention, but not, in any substantial measure, the country’s diplomatic endeavour in that testing time.

The background to India’s diplomacy during the Kargil ingress was provided by Vajpayee’s visit to Lahore in February 1999. That visit was a consequence of a political initiative on the part of Vajpayee and Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The two had first met in Colombo, on the sidelines of the Saarc summit, in July 1998, and had established a good rapport. Two months later, in their meeting on the margins of the United Nations General Assembly session in New York, they approved the modalities of the Composite Dialogue, and also decided to establish the Delhi-Lahore bus service.

After he had returned to power in February 1997, Sharif made efforts to tilt the country’s civilian-military balance in the former’s favour. He threw out the army chief, General Jahangir Karamat, in 1998, and hand-picked a relatively junior mohajir (a term to describe those who migrated from India during Partition) general, Parvez Musharraf, to succeed him. At this time Sharif’s father, the influential Mian Muhammad Sharif, made inroads among the army’s corps commanders. These were indications that the Sharifs may be able to contain the army’s role while India-Pakistan ties improved. Vajpayee’s visit strengthened this impression, despite some negative army signals prior to his visit, and some during it. Apart from Vajpayee’s statesmanlike gestures, the visit also resulted in the Lahore Declaration, the most substantial bilateral document after the Simla Agreement of 1972.

As India proceeded with its response to the intrusion, there was no way of firmly knowing the extent of Sharif’s involvement in the enterprise. It had to be logically assumed that he was fully complicit because of his seeming hold over the army. Besides, incontrovertible evidence had surfaced to show that Sharif had initially applauded the Kargil venture, though his father is believed to have admonished him for betraying Vajpayee.

At this stage, India had to rupture Sharif’s relations with the army. It successfully did so with the recording of Musharraf’s conversations with Chief of General Staff, General Aziz Khan, one of Indian external intelligence agency’s great achievements, playing a crucial part. Pakistan claimed that the mujahideen, and not its regular troops, had crossed the Line of Control (LoC). It linked the intrusion to militant and terrorist actions in the Kashmir Valley. This lie was exposed. The Kargil tapes showed that Pakistani forces were the aggressors, but eventually the Pakistani claim was torn to shreds when Indian troops recovered army documents and personal effects of its soldiers from recaptured posts. The message was effectively conveyed to the international community that Pakistani regulars were directly involved.

The Kargil ingress was a violation of the LoC in Jammu and Kashmir. Without conceding that its regular troops had crossed the LoC, Pakistan tried to obfuscate the issue by seeking to project that it had not taken any extraordinary step, and that both sides nibbled at the LoC from time to time. It also tried to sow further confusion, through counter allegations regarding the Indian presence in Siachen. Indian diplomats had to clarify the intricacies of the LoC to their international interlocutors. They effectively emphasised that Pakistan’s action was direct and unacceptable territorial aggression. They also stressed that no responsible nuclear weapons-possessing State had ever undertaken such provocative and dangerous action against a neighbouring nuclear weapon State.

Pakistan had hoped that the major powers would insist on an immediate ceasefire, and that would leave it in control of the Kargil posts. Indian diplomacy had to ensure that instead of doing so, these important countries, especially the United States, leaned on Pakistan to withdraw from Kargil. The US in particular had to be convinced that India meant business. The military action, where Indian soldiers took a great number of casualties, but pursued the recovery of posts with an iron will, impressed the Americans of India’s determination. This was backed by Vajpayee’s simple-but-forceful confidential message to President Bill Clinton that the Pakistani action threatened India’s northern defences, and would not be allowed to stand.

Months after India had militarily recovered some Kargil posts, through the heroism of its soldiers or where Pakistan retreated, a senior American diplomat told me that the US had told the Pakistanis early on that, in no case, would India allow Pakistan to get away with the Kargil intrusion. Clearly, diplomatic messaging coupled with military action made the required impact.

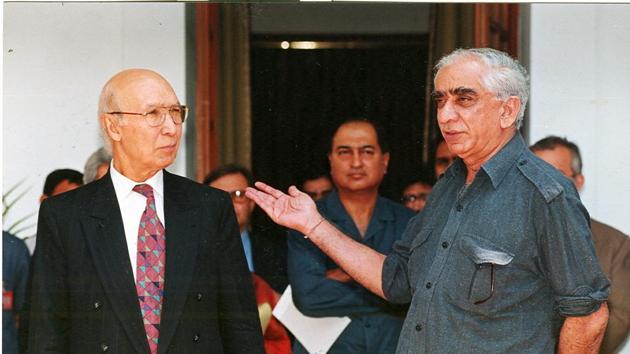

Throughout the tense period from the discovery of Pakistan’s Kargil surprise to India’s success, Vajpayee remained ethereally calm and unwaveringly focused on the objective of throwing out Pakistan from Kargil. National Security Adviser Brajesh Mishra ensured that all Indian institutions worked harmoniously to achieve the national aim of defeating Pakistan in Kargil. External affairs minister Jaswant Singh led the diplomatic effort from the front. Foreign secretary K Raghunath, ever thoughtful, sharpened India’s diplomatic arguments to profile Pakistan’s irresponsibility.

Pakistan foreign minister Sartaj Aziz visited Delhi in June even as the fighting was raging. He suggested a ceasefire and an examination of the Indian charge of LoC violation to the Indian leadership. Maintaining complete diplomatic courtesy, Vajpayee and Singh told Aziz that India would compel Pakistan to vacate the Kargil posts whatever be the cost, and Pakistan should see the writing on the wall. Vajpayee asked Aziz, “How did the Lahore bus reach Kargil?”

Pakistan’s Kargil intrusion made no strategic sense. It was premised on the Pakistani army’s prejudice that India (read Hindus) doesn’t have the stomach for sustained and difficult military actions. Now, Pakistani analysts uniformly blame a group of generals for Kargil. The problem is that the army has not abandoned its prejudices, and is engaged in the vain pursuit of confronting India, harming Pakistan and the region.

Vivek Katju is a former Indian ambassador. He was the joint secretary handling the Pakistan division, both during the Lahore Summit and the Kargil war, in the ministry of external affairs.

The views expressed are personal.

(This is the fourth of a six part series marking 20 years of the war.)