It is time to reset India’s approach to the environment

Expand the meaning of environmental damage and create institutionalised methods of ensuring its protection

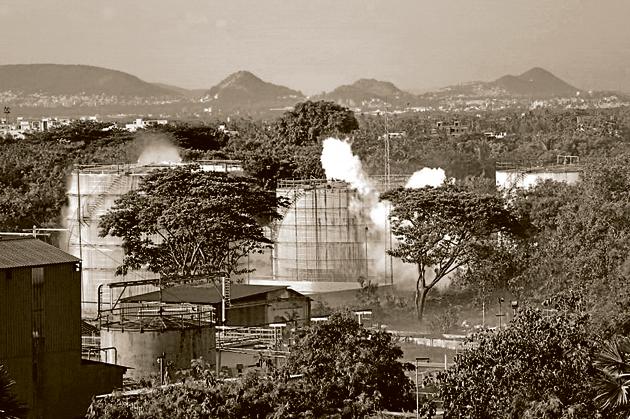

On Thursday, a gas leak from a polymer plant in Vizag killed 12 people. Hundreds were hospitalised; thousands exposed and evacuated. According to reports, the company, by its own admission in May 2019, didn’t have a valid environmental clearance. On the same day, seven workers were hospitalised due to a gas leak at a paper mill in Raigarh, Chhattisgarh.

The question we ask after every disaster is: Could it have been avoided? An even better question to ask is: How can environmental damage be avoided before it happens?

In March, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) delivered an elaborate judgment on illegal mining. In Dukalu Ram vs the Union of India, the court found Jindal Power Limited and Coal India Limited guilty of illegal mining in Raigarh, imposing ~160 crore as the cost for environmental damages. Significantly, the court’s order sets a template for what constitutes environmental damage, a concept worth exploring in greater depth.

India has said protecting the environment is desirable, and has led by hosting international meetings such as the Conference of the Parties for the Convention on Biological Diversity (2012), the United Nations Conference to Combat Desertification (2019) and the Convention on Migratory Species (2020). But we are yet to decide what constitutes damage to the environment.

This assumes greater significance as the Government of India is reworking its Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification. Such assessments are done to find out the impact a project has on the environment. Getting environmental clearances depends on this assessment. The 2020 EIA draft introduces a host of changes, introducing the concept of post-facto clearance. This means that projects that did not apply for EIAs and environmental clearances — and subsequently started construction or are up and running — will be appraised and may receive clean chits. If found to be run in a “sustainable” fashion, they will be allowed to apply for environmental clearances. If found to be damaging the environment, closure of the project or other actions will be recommended.

But what is environmental damage? The 2020 draft says the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) should set the criteria for damage assessment and remediation. The CPCB was created in 1974 under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act; it also carries out functions under the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981. Thus, the CPCB’s mandate relates to maintaining clean water and air and preventing their pollution.

Yet, though pollution or leaks are one of the most visible indicators of environmental damage, they aren’t the only ones. In this regard, the NGT order is illustrative. The order found illegal mining to be harmful to the environment on counts of waste dumping, proximity to residences, causing the drying up of ponds, air pollution through poor transport of coal, loss of groundwater (this amounts to degradation), lack of provision of health care, and loss of ecological services.

The most significant in the case of long-term damage is the loss of ecological or ecosystem services. Ecosystem services refer to the services provided by healthy nature, which include things like pollination, quality of life, bio-filtration and more. In the Raigarh mines, apart from the usual complaints of air and water pollution, villagers complained of “raging fires” at the mining sites that caused turbidity and affected their health.

A few things should be kept in mind. First, the EIA notification draft should broaden the scope and understanding of environmental damage, beyond just pollution. Environmental damage, including purported long-term damage to ecological services, should be part of the assessment and the EIA notification.

Second, the world after the coronavirus pandemic has shown us that several human-led activities create novel interfaces that further lead to consequences we can’t control, such as viruses caused by the disturbance to wildlife. We are also seeing how pristine the environment is without our interventions. The images released by NASA reveal that the air over the northern Gangetic plain is the cleanest it has been in 20 years. This clear view gives us a chance to plan projects in a way that actively protects the environment rather than “balances” it against political goals.

Finally, if we can put India under lockdown, and run offices remotely, it means we can indeed do the impossible as long as political and societal will exists for it. A clean environment — on the heels of an ongoing pandemic — is a social goal, as much as one mandated by international conventions.

This is the time to put trust in science and technical expertise, and create a broader understanding of what environmental damage is. Once we fully map it, we can set about preventing it.

We tend to pray after environmental catastrophe strikes. But we need more than thoughts and prayers to institutionalise environmental protection. This is the best time to understand how environmental damage impacts ecological services, and how this should reflect in the EIA processes. As we pick up the pieces left behind from a virus, we must plan to avoid more environmental grief.