India needs to acknowledge the gaps in data protection and rights of children

Children occupy a unique position within any legal framework. On the one hand, they are distinguished from adults by virtue of their vulnerability. On the other hand, there is a tendency on the part of lawmakers — and, indeed, society — to equate vulnerability with dependence, and completely efface children’s autonomy and decision-making capacities

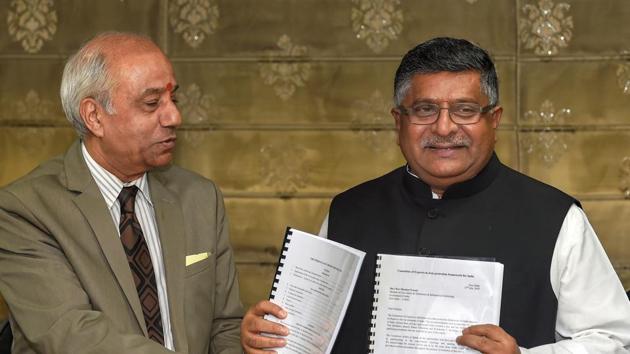

Over the last ten days, the Justice BN Srikrishna Report on data protection, and its draft Personal Data Protection Bill of 2018, has been subjected to extensive analysis. Commentators have argued that it does not go far enough, or that it goes too far, or even — for the odd analyst — that it goes just the right distance. While the debate promises to rumble on in the coming months, as the government has promised wide-ranging consultations, there is one relatively forgotten aspect of the report and the Bill that deserves focus: data processing and the rights of children.

Children occupy a unique position within any legal framework. On the one hand, they are distinguished from adults by virtue of their vulnerability. Consequently, there are invariably some special or “protective” measures designed to further their interests, which would be considered intolerable and a denial of choice if applied to adults. On the other hand, there is a tendency on the part of lawmakers — and, indeed, society — to equate vulnerability with dependence, and completely efface children’s autonomy and decision-making capacities by purporting to act on their behalf, and for their best interests.

In an attempt to forge a middle path, the Personal Data Protection Bill does three things. First, it defines a child as being under eighteen years of age. The report — which explains many parts of the Bill — acknowledges that, in the modern era, eighteen might be setting the overly paternalistic, but justifies it on the basis that the Indian legal system — and especially the Indian Contract Act — sets the age of majority as eighteen. Secondly, the Bill defines a class of entities who operate commercial websites or online services directed at children, or process large volumes of the personal data of children, as “Guardian Data Fiduciaries”. Guardian data fiduciaries are absolutely barred from activities considered specifically harmful, such as profiling, tracking, behavioural monitoring, or targeted advertising. And thirdly, for all other data processing, the Bill requires “appropriate mechanisms for age verification and parental consent”.

There are, however, a few concerns with the manner in which the Srikrishna Personal Data Protection Bill deals with this admittedly vexed and delicate issue. The first is that it appears to deny to legal minors any effective participation in decisions about how their data is to be processed. The fact that the Indian Contract Act defines majority — and thereby, the capacity to contract — at eighteen does not preclude a Data Protection Bill from fixing a different age, especially since the kinds of instant contracts people enter into in the digital world are of a vastly different character than the contracts envisaged by a law enacted in 1872. However, even if were to grant that point, there are ways of enhancing the participation of minors even while maintaining a regime of parental consent. For example, there could be a statutory requirement that a “data fiduciary” or a “data processor” (the two terms used by the Bill) explain to a minor, in a simple and explanatory manner, of the need for care in handling data concerning herself, before the stage of parental consent. This would treat children with due respect and as partners in the processing of their data, instead of subjects at the altar of parental consent.

The second — and perhaps more important — omission from the Bill is the right of a child to opt out on attaining majority. If the basis of parental consent is that the parent stands in as a proxy for determining the child’s best interests, then it stands to reason that at the point of majority — when the erstwhile child is now deemed to exercise her own right to self-determination — an individual have the right to review the decisions made on her behalf, and “opt out” if she feels that they were wrongly made. This could be resolved by granting an individual the right, on attaining majority, to be informed of the terms on which her personal data has been collected, alter or rescind the terms on consent, and require the destruction of all personal data related to her (for example, the draft Bill of the Save Our Privacy Collective, which has also been put up online for comments and to which this author contributed, has language to this effect).

The deeper problem, ultimately — as the Srikrishna Report acknowledges — is an outdated legal landscape where the morals of 1872 still govern crucial issues such as majority and the capacity to make choices and enter into contracts. Throughout the world, legislatures and courts (especially the Constitutional Court of Colombia) are acknowledging the right of children to self-determination, decisional autonomy and choice, even where those choices conflict with what parents or the State believes is in their “best interests”. Moving forward, a Data Protection Act would be a good starting point for India to acknowledge that reality as well.

Gautam Bhatia is an advocate in the Supreme Court and a member of the SaveOurPrivacy.in collective

The views expressed are personal