Eliminate State and social interference in matters of conscience

The UP conversion law is unconstitutional. But the debate does not end with this one law, as it also replicates many existing provisions from other laws, which have been left standing for too long. India cannot call itself a constitutional democracy until social interference in matters of conscience is eliminated from its laws, once and for all.

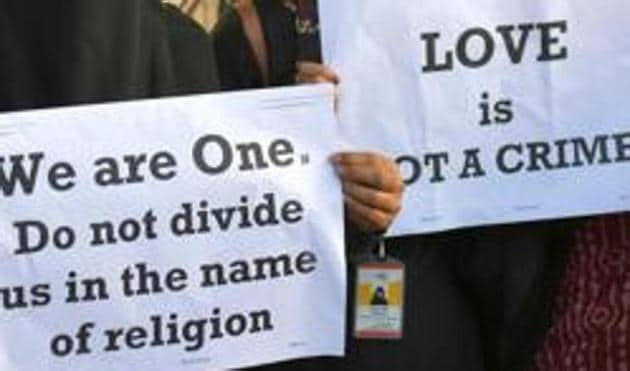

Uttar Pradesh (UP)’s Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion law — colloquially called the “love jihad law” — has attracted controversy ever since it was initially enacted as an ordinance two months ago. On the surface, the law proclaims itself to be against “unlawful conversions”, which, in turn, are defined broadly as conversions secured through coercion or other forms of inducement.

To start with, it is unclear why the State should be specially concerned with something as personal as religious conversions, when the Indian Penal Code already has provisions against both criminal intimidation and various forms of fraud. However, as such laws have existed on the statute books for many years — and have been upheld by the Supreme Court — their continued existence needs a larger and longer debate.

More specifically, however, there are two ways in which UP’s law contravenes fundamental principles of the Constitution. First, it discriminates on the basis of gender. The law provides for greater penalties if the unlawful conversion is with respect to a minor, a member of a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe, or a woman. Furthermore, the law also stipulates that an unlawful conversion conducted for the purpose of marriage will be void in cases where the woman has been unlawfully converted before the marriage. This provision makes it clear that the law continues to be based on a patriarchal mindset that views women as lacking agency and autonomy, and therefore in need of “special protection.”

Such logic has been strongly repudiated by the courts — most recently while striking down the criminalisation of adultery, which had a very similar gender asymmetric provision — and it has been made clear that the Constitution does not allow ostensibly “beneficial” laws for women that are based on patriarchal or stereotypical assumptions.

Second, the law requires an advance notice of any conversion to be provided to the district magistrate, who is then required to initiate an inquiry — through the police — into the “real intention” behind the conversion. To this is added the fact that the law places the “burden” of proving that a conversion is not illegal upon the person who desires to convert (or someone who has facilitated the conversion). Shorn of legalese, therefore, the effect of the law is that any person who wants to change their religion must first convince the State and the police that they are doing so for reasons that the State deems to be genuine.

It should be clear that the law infantilises Indian citizens, reduces them to the level of subjects, and authorises State intrusion into the most personal of domains, that of individual conscience. Secular law already has provisions penalising coercion, intimidation, and fraud, and there is no reason why coercion or fraud deserves any special treatment where religion is concerned.

The requirement of a public notice accompanying a decision of conversion also requires a larger debate, as variants of it are found in many laws, including the Special Marriage Act, which was ostensibly enacted to protect the rights of inter-faith couples. Let us, for the purposes of argument, assume for a moment that the State has some interest in regulating valid marriages and conversions. This does not change the fact that both marriage and conversion are decisions that lie firmly within the domain of individual choice, and individual privacy.

There is, therefore, no justification for requiring people choosing to be married under the Special Marriage Act — or individuals choosing to convert — to publicly announce their intention to do so. In essence, this sanctifies social interference with individual privacy, and goes far beyond any interest the State may have to ensure that the laws are upheld.

The UP conversion law is unconstitutional. But the debate does not end with this one law, as it also replicates many existing provisions from other laws, which have been left standing for too long. India cannot call itself a constitutional democracy until social interference in matters of conscience is eliminated from its laws, once and for all.

Gautam Bhatia is a Delhi-based advocate

The views expressed are personal