Analysis| What the 2019 and 2020 skirmishes tell us about de-escalating conflicts

The Indo-Pak conflict after Balakot and the recent US-Iran clash show what ingredients help defuse tensions

The parallels between the recent United States (US)-Iran clash and the February 2019 India-Pakistan conflict are being widely noted. Indeed, there are uncanny similarities between the two episodes. I will first recount the two major similarities and then draw the lessons the two conflicts have to offer on escalation dynamics.

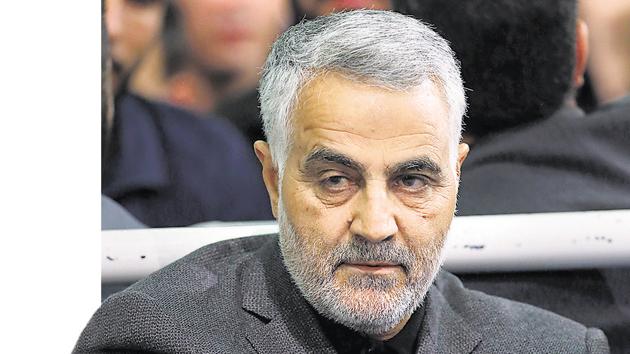

First, in both cases, the stronger power showed a tremendous appetite for risk-taking. While the impact remains disputed, India did breach a red line by dropping ordnance on proper Pakistani territory beyond the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. The US, on the other hand, carried out a targeted killing of Qassem Soleimani, a top Iranian State official. The Indian action in Balakot was a response to a terrorist attack in Pulwama, but it was also presented as “a pre-emptive strike” to prevent future attacks. Donald Trump, the US President, justified Soleimani’s killing to prevent “imminent” attacks in addition to avenge “recent attacks on US targets” that had already been concluded.

Second, the weaker power responded, in both cases, with an aim of restoring deterrence. The responses were calibrated in a manner so as to leave room wide open for de-escalation. Pakistan claimed it merely wanted to show resolve and deliberately missed when it could have targeted Indian military installations. Iran, it appears based on the evidence so far in the public domain, used precision targeting in order to avoid American casualties. While the Indian Air Force lost a Mig-21 Bison, Pakistan quickly returned the captured pilot so as to not give India further chance of escalation.

There are four broad factors that contributed to the eventual restraint, in both cases.

First, both India and Pakistan are vulnerable to each other’s nuclear weapons. The fear of escalation, right to the nuclear level, works as a significant restraining factor. This also leads to heightened global interest and counselling from major powers. One has traditionally assumed that the fear of nuclear escalation works disproportionately on India. However, the quick return of captured pilot showed that Pakistan was no more prepared for escalation either. In the US-Iran case, there is no mutual nuclear vulnerability. The presence of US troops in Iraq and other countries in the region, nevertheless, plays a similar role and some sort of mutual vulnerability is created. While Iran desires a complete US withdrawal from the region, such a drawdown would mean that the US could, in situations of conflict, use its long-range missiles, aircraft carriers and bombers to damage Iranian assets while Tehran won’t have much to target with its current levels of capability. Mutual vulnerability, hence, is the key to de-escalation.

Communications to one’s audience is the second factor contributing to restraint. India could present its Balakot operation as a success. It also claimed that it shot down a Pakistani F-16 on the next day, though it failed to produce enough evidence to prove that. Pakistan projected the return of Indian pilot as an act of magnanimity rather than one of necessity. Both sides, therefore, were well able to project victory to their domestic audience. Iranian media, similarly, claims that 80 Americans died in its attack on the two Iraqi military bases. The US has been able to de-escalate because there were no American or allied casualties. The use of ballistic missiles by Iran could have been seen as escalatory and responded to by further escalation. However, the Trump administration has, for now, decided to look past this inconvenient fact.

Third — and this is more of a hypothesis which will need rigorous testing — the de-escalation is not just a factor of the ability of leaders to sell victory to the domestic audience, but also the audience’s ability to restrain the leaders. Even among the hawkish section of the domestic audience, a fraction of people are ready to press for de-escalation, or not press for further escalation, if reasonable face-saving exit options are available. A test of this claim would be to examine the divergence in tones of editorials in Indian newspapers before and after the capture of the Indian pilot on February 27, 2019. Trump’s ability to exit also shows that he was able to rein in the warmongers in his administration and the Republican party. Once the bombs and missiles start flying, even some hardcore proponents of war turn squeamish.

Lastly, luck does have a role to play in de-escalation. If the Indian pilot had been killed in the crash or, worse, lynched by a mob in Pakistan, the eventual outcome might have been very different. If the Iranians had, even accidentally, killed a number of American personnel in Iraq, US response could easily have been very aggressive. That luck can play such a huge role, in itself, creates a deterring effect. How strong is that deterrence is very difficult to pin down — because when a dog does not bark, we don’t know why it did not, or if it even wanted to bark in the first place. For what it is worth, a Pulwama-scale terrorist attack has not been repeated so far. The decapitation of Soleimani does not itself create deterrence but a realisation that another ambitious Iranian operation could bring it, once again, this close to a war with the US can induce some caution.

Iran’s safest bet — not perfectly safe, as nascent proliferators can become military targets — would be to rush to get its nuclear deterrent.

Kunal Singh is a PhD candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The views expressed are personal