In 2018, films by all three Khans — Race 3, Thugs of Hindostan and Zero — bombed. Shah Rukh, Aamir and Salman Khan all turn 57 in 2022. No new superstars have stepped up to take their place, and this is altering the look and sound of Bollywood.

The 2010s saw sweeping change in Bollywood. There was the fading of formulaic cinema and the transformation of the song-and-dance sequence. And, as audiences and platforms became more diffused, there was the clear dissolution of a crucial Bollywood entity: the superstar. The three Khans (Aamir, Salman and Shah Rukh) along with Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgn had ruled the Hindi film industry for 25 years. Cracks in their kingdoms began to appear in 2018, the year of the appalling Race 3, Thugs of Hindostan, and Zero. All three films offered a headlining superstar, plenty of lip-syncing and histrionics, but nothing compelling in writing or plot. All three films bombed.

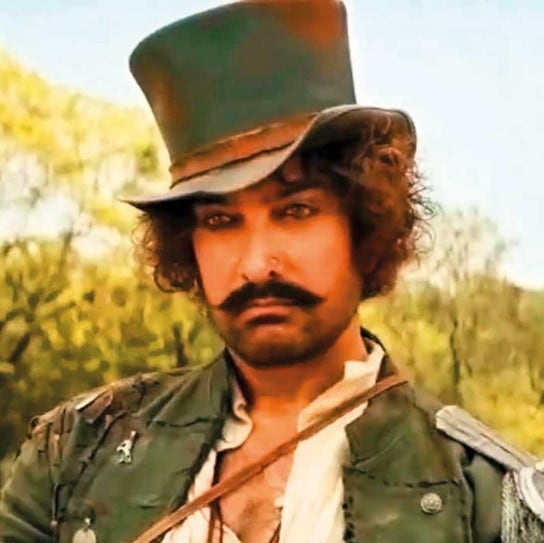

Aamir had to apologise to fans for the disappointment that was Thugs of Hindostan. Salman appeared unable to change gears, and followed with more disasters such as Radhe and Antim, while for Shah Rukh, the alarm had gone off much earlier with the non-acceptance of Dilwale (2015), Raees (2017), and Jab Harry Met Sejal (2017). Zero would be the last straw. He stepped away entirely; his next film (barring a few cameos) will only be out in 2023.

Aamir Khan had to apologise to fans for the disappointment that was Thugs of Hindostan. Meanwhile, films with unusual storylines but no major star at the helm (Sonu Ke Titu Ki Sweety, Badhaai Ho) were raking it in.

Meanwhile, audiences were thronging the theatres for the kind of fare they had now come to expect from the vast array of film industries at their disposal online and on streaming platforms. They were looking for strong plots, the element of surprise, as well as excellence in performance and production levels.

Films such as Raazi, Article 15, Stree, Sonu Ke Titu Ki Sweety, Badhaai Ho and Andhadhun were successful even without a superstar. Everyman actors such as Rajkummar Rao, Taapsee Pannu and Ayushmann Khurrana became, of all things, bankable.

Buddy-romance Sonu Ke Titu Ki Sweety (2018), starring Kartik Aaryan and made with a budget of ₹35 crore, earned ₹ 150 crore worldwide. Badhaai Ho (2018), a late-in-life pregnancy tale starring Khurrana and Neena Gupta, was made on a budget of ₹29 crore and earned more than ₹200 crore worldwide.

Raazi (2018), an espionage tale starring Alia Bhatt and Vicky Kaushal, was made on a budget of ₹35 crore and earned ₹200 crore worldwide. It became one of the highest-grossing Indian films featuring a woman protagonist, and made Bhatt one of the most bankable stars of her generation.

The stories that were drawing these large crowds were like nothing the industry had seen before. In Bala (2019), Khurrana is coming to terms with premature baldness. In Rashmi Rocket (2021), Pannu plays an athlete battling hyperandrogenism. Badhaai Do (2022; starring Rao and Bhumi Pednekar) is a queer drama / romance.

The barrier between small films and commercial success is gone; the line between independent films and blockbusters was fading. This has only intensified in the pandemic, which forced theatres shut and disrupted the habit of theatre-going for at least two years.

In trade magazines, producers, distributors and analysts began to give confused interviews about how the power of the superstar was being replaced by the overriding need for “storylines” and “quality content”. The confusion was, in a sense, understandable. For decades, some superstars had make the same gesture, told a similar tale, smiled the same smile, and it worked.

Perhaps responding to the sense of shaken nerves in the industry, Salman Khan, while promoting Antim in 2021, said: “The era of superstars will never fade. We will go, someone else will come up.”

The Khans all turn 57 in 2022; Kumar will be 54; Devgn is 53. Despite early promise, stars such as Ranbir Kapoor, Ranveer Singh and Varun Dhawan haven’t turned the corner into superstardom. No new superstars have emerged.

Raazi (2018), an espionage tale starring Alia Bhatt and Vicky Kaushal, was made on a budget of ₹35 crore and earned ₹200 crore worldwide.

Meanwhile, the “sound” of the Hindi film has changed dramatically. Where legendary composers once helmed entire projects, the 2010s saw the rise of multiple music directors working on each film, primarily because it was no longer about marrying music and sequences to storyline, but about creating standout elements (the item number, the dance number, the ballad).

This trend can, in a sense, be traced to 1998 and the Salman Khan-starrer superhit Pyaar Kiya To Darna Kya (with composers Jatin-Lalit, Sajid-Wajid and Himesh Reshammiya).

This has created more opportunities for promising musicians looking for a break, but many argue that it has made the sound of the mainstream Bollywood hit a disjointed thing. It has also meant the decline of actor-singer collaborations such as the ones between Raj Kapoor and Mukesh, Dilip Kumar and Mohammed Rafi, and Aamir Khan and Udit Narayan, where one singer was the “voice” of a star.

With songs generally playing in the background today, few actors lip-sync any more. Even Sanjay Leela Bhansali, a great champion of lip-synced songs, used the songs in Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022) as background; Alia Bhatt dances but does not “sing”.

Is it an evolution or a revolution? Will the lip-synced song and the traditional musical return? With Bollywood, one never says never, but it is unlikely that the enmeshed jugalbandi of the mainstream Hindi tale, tune, actor and singer will recur on the big screen.

(Yasser Usman is a journalist who has authored best-selling biographies of Guru Dutt, Rajesh Khanna, Rekha and Sanjay Dutt)